Mainstream economists argue that time makes money. According to the Austrians, production takes time, because of “roundabout” methods, which creates the additional value that flows to capital. Neoclassical economists have a different theory: the return to capital is the reward for savings created by time-deferred consumption. However, in both cases, time is the basis of the value that is captured as profits.*

In Cosmopolis, the 2003 novel by Don DeLillo (adapted for the cinema by David Cronenberg in 2012), Erik Packer’s “chief of theory,” Vija Kinski, explains they have it backwards:

“Money makes time. It used to be the other way around. Clock time accelerated the rise of capitalism. People stopped thinking about eternity. They began to concentrate on hours, measurable hours, man-hours, using labor more efficiently.”. . .

“Because time is a corporate asset now. It belongs to the free market system. The present is harder to find. It is being sucked out of the world to make way for the future of uncontrolled markets and huge investment potential. The future becomes insistent. This is why something will happen soon, maybe today,” she said, looking slyly into her hands. “To correct the acceleration of time. Bring nature back to normal, more or less.”

DeLillo (via Kinski), as it turns out, is right—at least when it comes to healthcare in the United States.

According to a series of reports in the most recent issue of the British medical journal The Lancet (confirming the results of a study I wrote about last year), increasing inequality means wealthy Americans can now expect to live up to 15 years longer than their poor counterparts.

As economic inequality in the USA has deepened, so too has inequality in health. Almost every chronic condition, from stroke to heart disease and arthritis, follows a predictable pattern of rising prevalence with declining income. The life expectancy gap between rich and poor Americans has been widening since the 1970s, with the difference between the richest and poorest 1% now standing at 10.1 years for women and 14.6 years for men.

The obscenely unequal distribution of income and wealth in the United States is responsible for increasingly unequal health outcomes.**

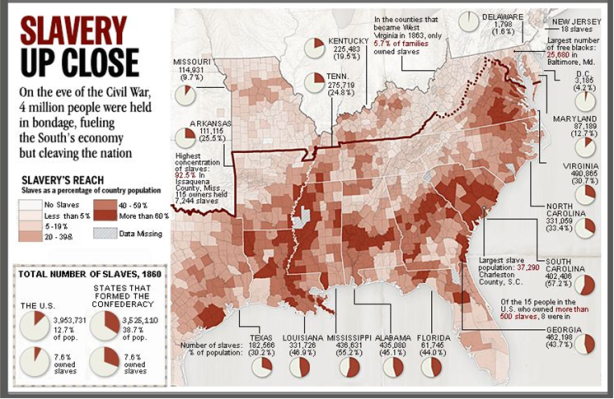

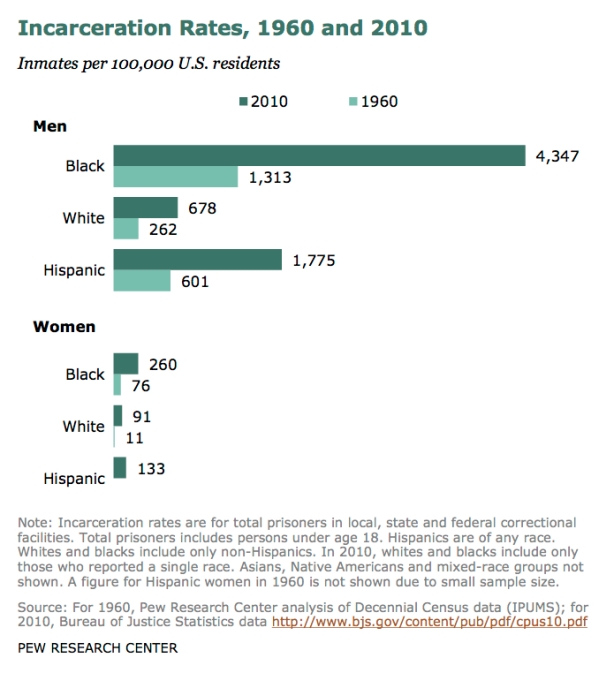

In addition, both structural racism (the “systematic and interconnected web of institutions and factors that lead to adverse health outcomes”) and mass incarceration (on prisoners, their families, and their communities), according to two other studies, exacerbate class-based health inequalities.

While the authors of one of the studies argue that “the health-care system could soften the effects of economic inequality by delivering high-quality care to all,” they conclude that the U.S. system falls “far short of this ideal.” That’s because disparities in access to care—based on income, race, and unequal rates of imprisonment—are far wider in the United States than in other wealthy countries.

Moreover, according to another study, even after the Affordable Care Act’s coverage expansion, twenty-seven million Americans remain uninsured and, even for many with insurance, access to affordable care remains elusive. At the same time, unneeded and even harmful medical interventions remain common (due, in part, to the fragmented health-care delivery system), corporate administration consumes nearly a third of health spending, and wealthy Americans consume a disproportionate and rising share of medical resources.

Thus, the editors of the series conclude,

Although a Series about health published in a medical journal may seem far removed from the political arena where much of the decision making about how to address these factors lies, the message of this collection of papers transcends that distance. . .it is no radical statement to say that Americans deserve better and, most importantly, the time for action has arrived.

It is time, in other words, to make the necessary changes so that money is available to provide decent healthcare for all Americans.

*One neoclassical economist, the late Nobel laureate Kenneth Arrow (pdf), did have the intellectual honesty to admit that the absence of future markets represented a severe shortcoming of capitalism, a coordination failure, and supported the case for a socialist economy.

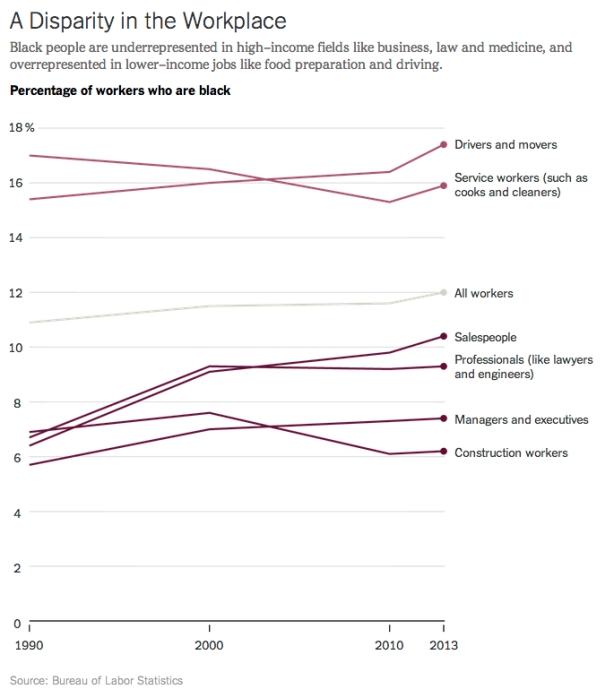

**The authors also note that the medical system in the United States itself influences inequality, as an employer of nearly 17 million Americans. Although physicians and nurses are generally well paid, many other health-care workers are not:

The health-care system employs more than 20% of all black female workers; more than a quarter of these health-care workers subsist on family incomes below 150% of the poverty line, and 12.9% of them are uninsured.