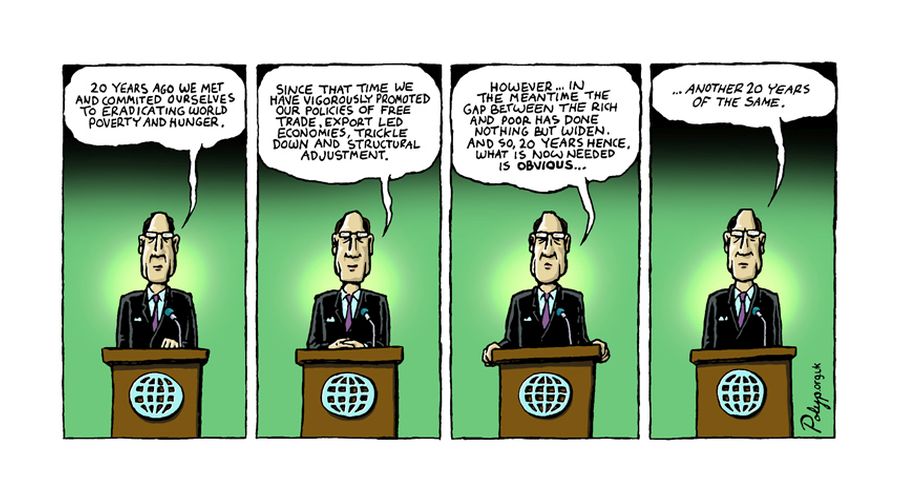

2019 was a very good year for the world’s wealthiest individuals. The normal workings of global capitalism created both more billionaires and more combined wealth owned by those billionaires.

According to Wealth-X, which claims to “have developed the world’s most extensive collection of records on wealthy individuals and produce unparalleled data analysis to help our clients uncover, understand, and engage their target audience, as well as mitigate risk,” the size of the global billionaire population increased strongly in 2019, rising by 8.5 percent

to 2,825 individuals, while their combined wealth increased by 10.3 percent to $9.4 trillion.

To put that into perspective, the world’s real Gross Domestic Product grew by only 2.9 percent (International Monetary Fund) in 2019—while the value of global equities, which is key to billionaires’ wealth, soared by more than 25 percent (MSCI World Index).

The United States still leads the list of the world’s billionaire population and their wealth. In 2019, the number of American billionaires rose by almost 12 percent to 788 individuals, accounting for 28 percent of the global billionaire population (China has the next highest share at 12 percent). Cumulative billionaire wealth in the United States increased by 14 percent to $3.4 trillion, more than the combined net worth of the next eight highest-ranked countries and equivalent to a 36 percent share of global billionaire wealth.*

What about the novel coronavirus pandemic?

According to Bloomberg, only two of the world’s 10 richest people have seen their wealth decline in 2020: luxury mogul Bernard Arnault and Berkshire Hathaway Inc.’s Warren Buffett. Everyone else, whose wealth is tied to technology holdings (except for Mukesh Ambani, the Indian billionaire who chairs and runs oil and gas giant Reliance Industries), has seen their individual and collective wealth increase—none more so than Jeff Bezos (the Amazon.com Inc. founder who has seen his net worth soar by $63.6 billion this year) and Elon Musk (whose net worth has more than doubled to $69.7 billion on the back of surging Tesla Inc shares).**

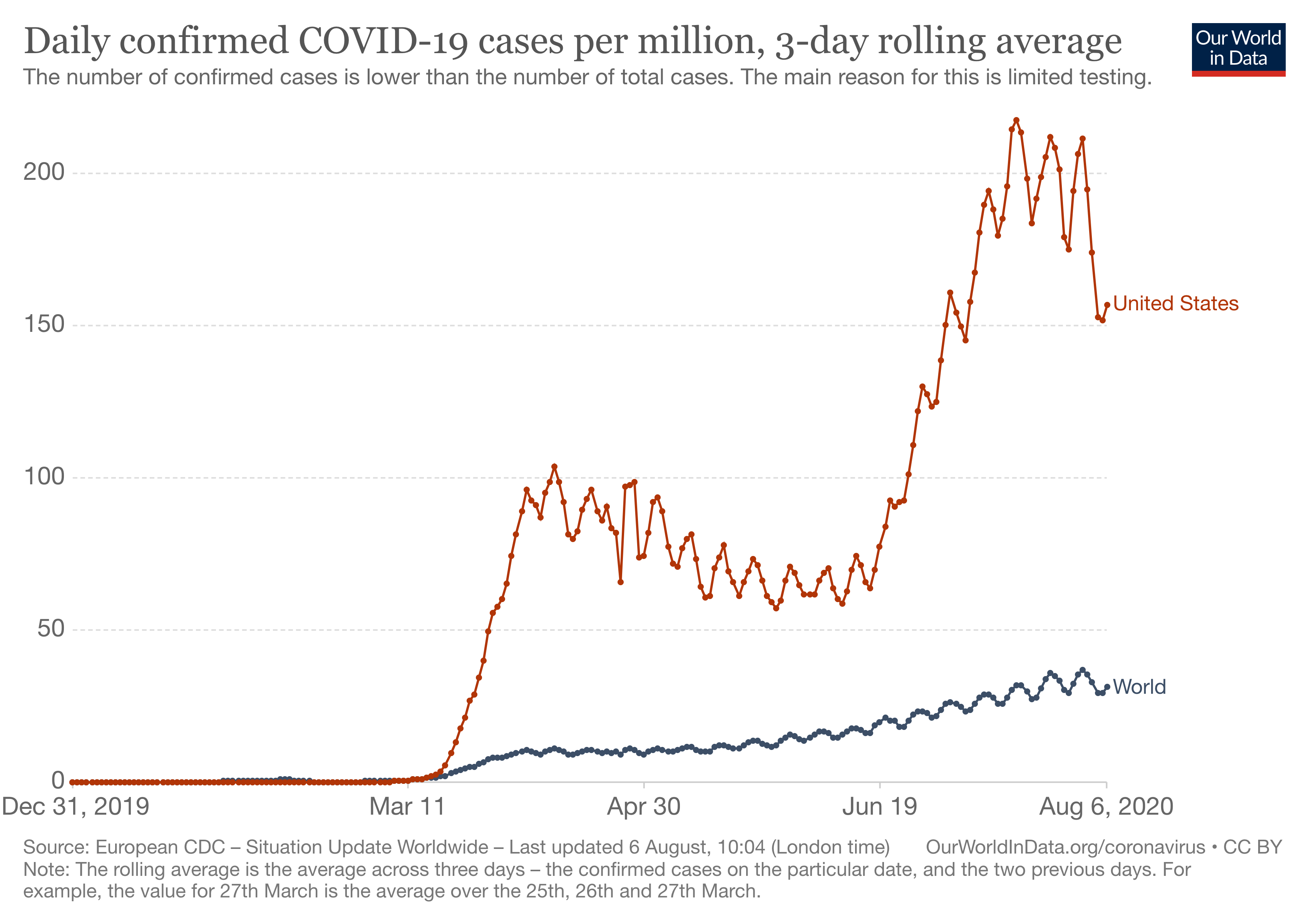

On a global level, billionaires tied to technology businesses have outperformed all others, especially those whose wealth is tied to the automotive, shipping, media, textiles and apparel, and aerospace (less so defense) industries. They, of course, are the ones who most want to see a quick solution to the pandemic and a reopening of economic activity around the world.

In general terms, wealthier billionaires are more exposed to the ebbs and flows of the stock market, while those at lower tiers tend to have more of their wealth in private holdings, likely to be their primary business. For example, those in the two highest billionaire wealth tiers—above $10 billion— hold between almost half and more than three-quarters of their assets in public holdings. These individuals have withstood significant volatility in their wealth as stock markets first fell considerably and then rebounded equally dramatically—this past Friday, to a new record high in the United States—since the beginning of the pandemic.

So, what are the world’s billionaires, in the United States and around the globe, doing with their wealth in the midst of the pandemic? We know they’re not particularly worried with the same problems as their predecessors, the Robber Barons, whose enormous economic power in the United States created a fierce counter-reaction, in militant labor unrest and the adoption of reforms that once seemed radical, like the Sherman Antitrust Act and a federal income tax.

At least so far. . .

Instead, according to Wealth-X, they are

working with their wealth advisors and planners to ensure their financial holdings and wealth plans (whether concerned with investment diversification, wealth transfer or philanthropic aims) remain up to date and in the best possible state given the evolving global situation.

They’re also concerned about their own safety and new forms of luxury consumption. According to the Wealth-X Global Luxury Outlook 2020. “The wealthy’s mindset around what luxury is has changed—their priorities have shifted towards their families,” Jaclyn Sienna India, CEO of luxury travel company Sienna Charles, said in the report. “Luxury now includes a second passport, access to healthcare and the freedom to go when and where they feel safe and secure.”

“Quite a few wealthy people are looking for exclusive safe havens in the form of second homes—safety has become a priority for them,” Alistair Brown, CEO of Alistair Brown International Real Estate. “But with this purchase, they expect access to established locations often via residency and additional passports as well as access to medical help.”

Additionally, the wealthy have become increasingly accustomed to purchasing luxury goods online since the pandemic, as high-end brands expand their digital offerings, the report said.

“The wealthy continue to value luxury as they did prior to Covid-19. However, the way they buy luxury has changed, with more having moved to making their purchases online,” Winston Chesterfield, principal of luxury watch company Barton.

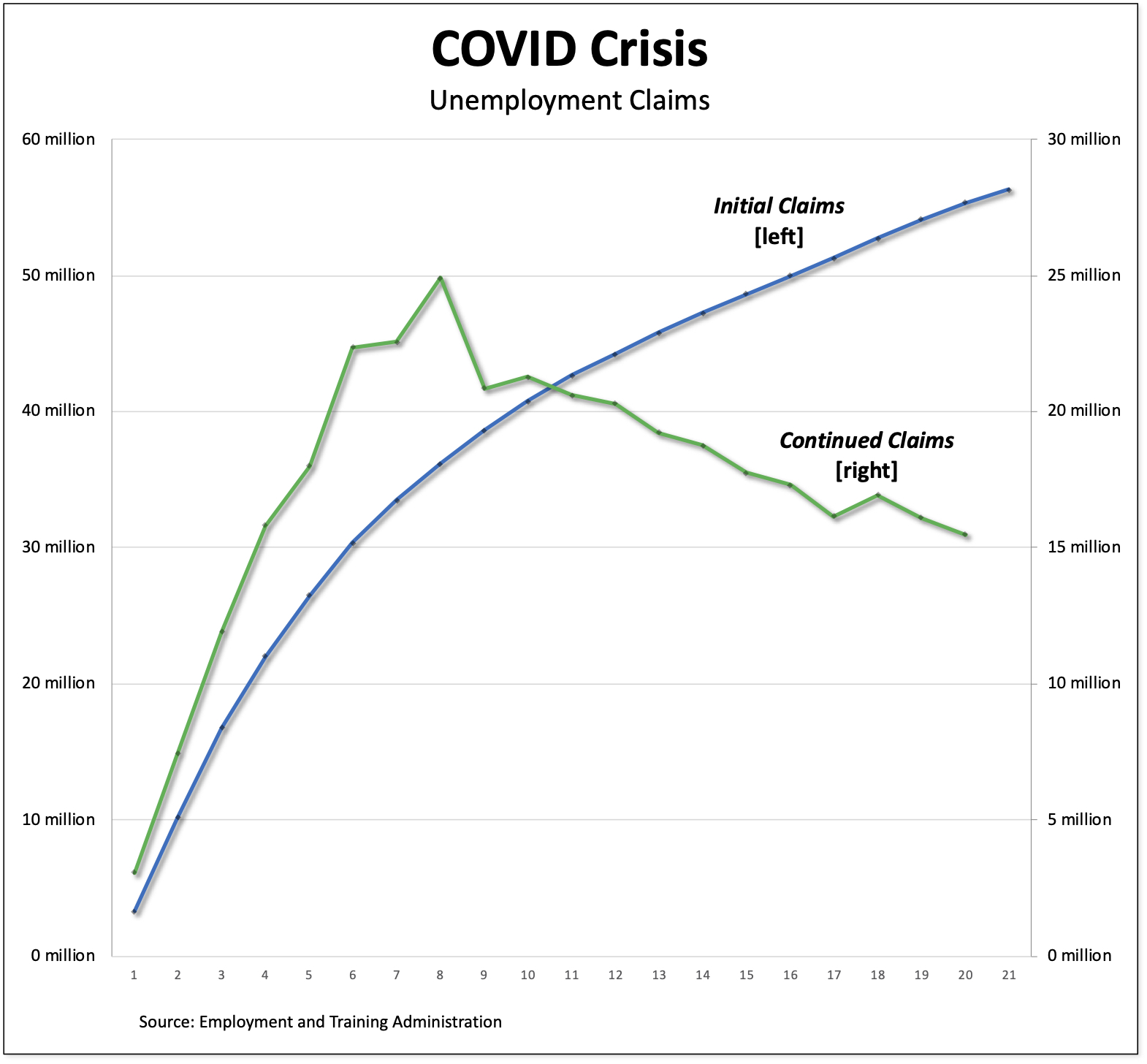

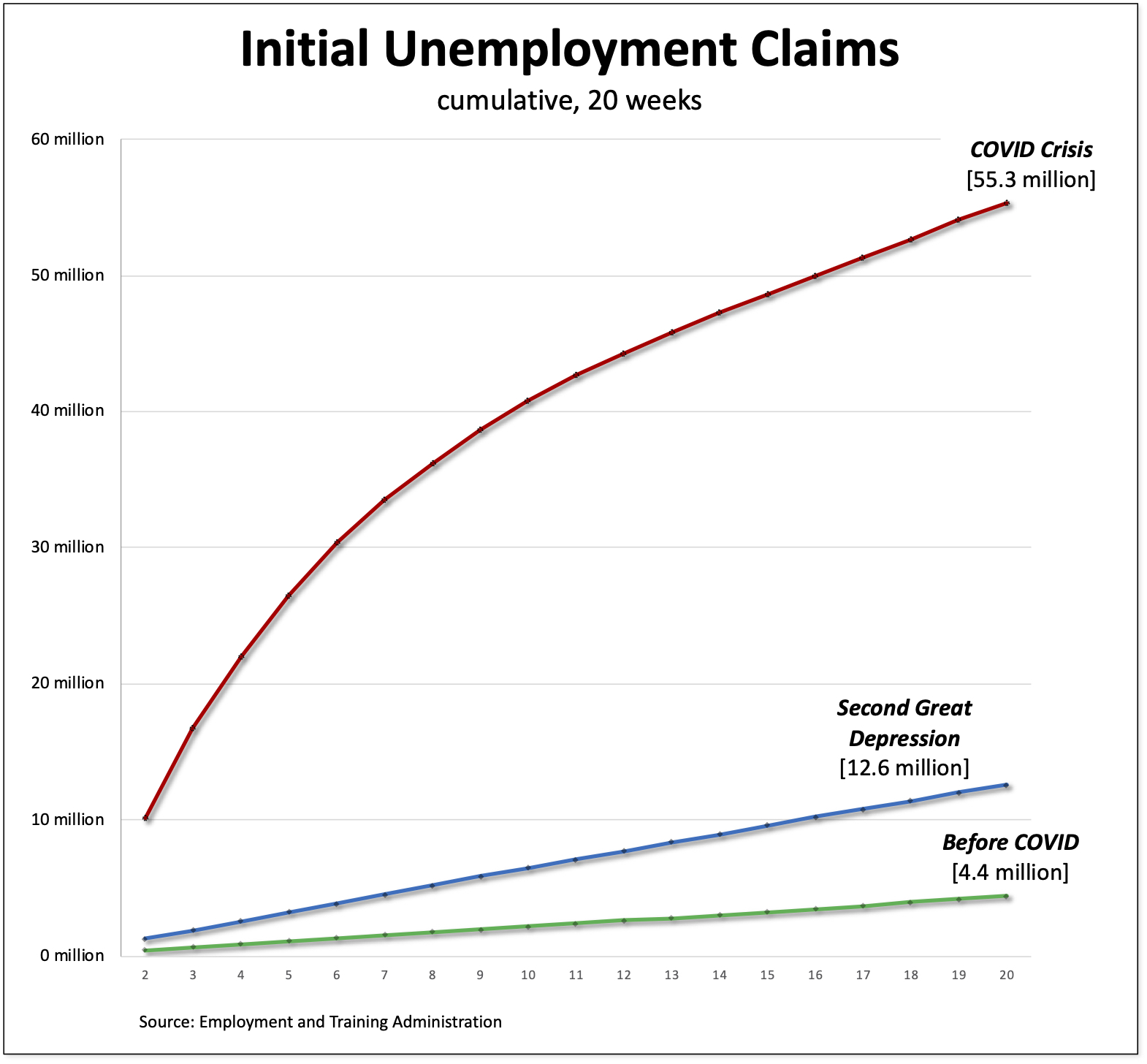

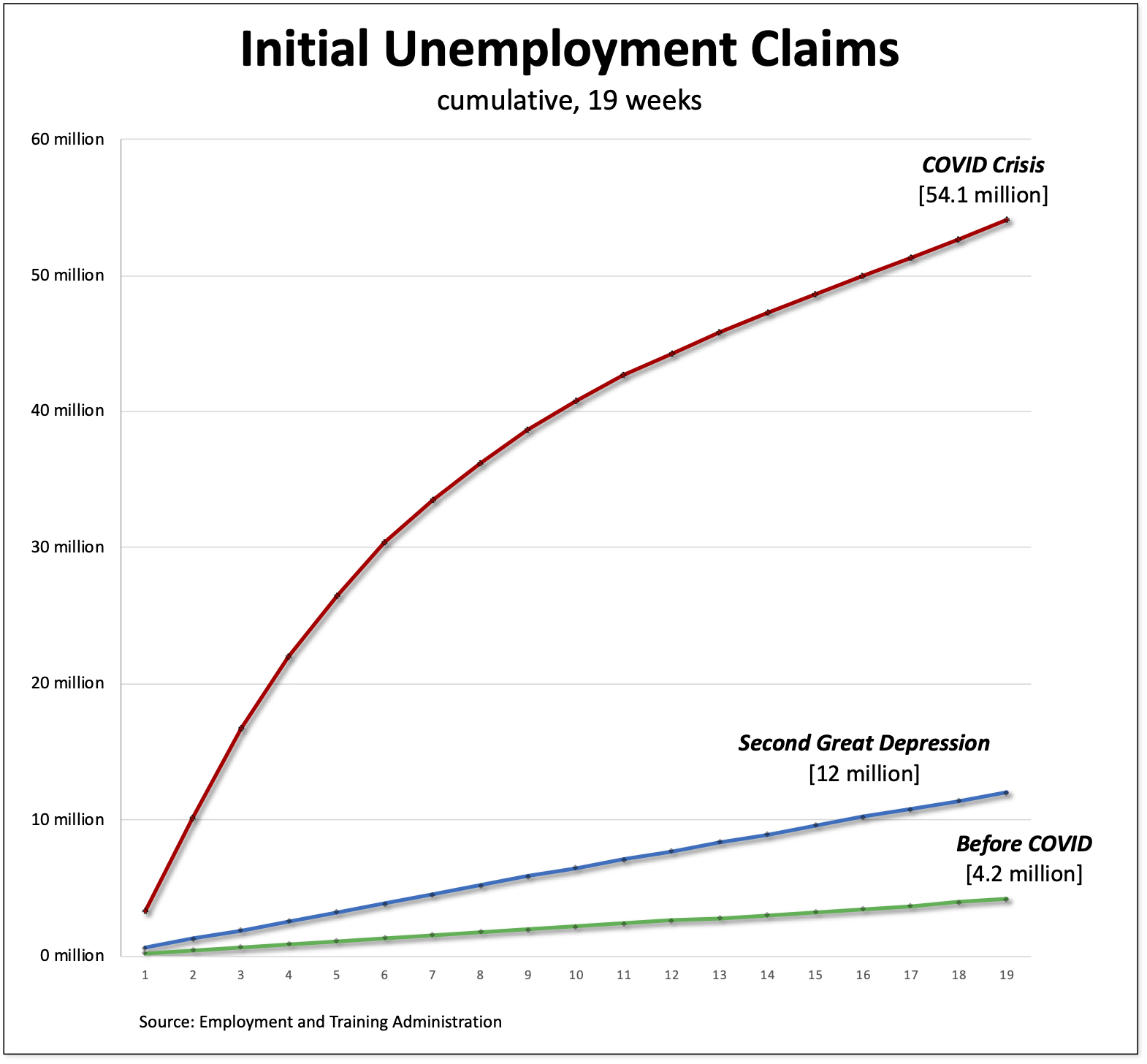

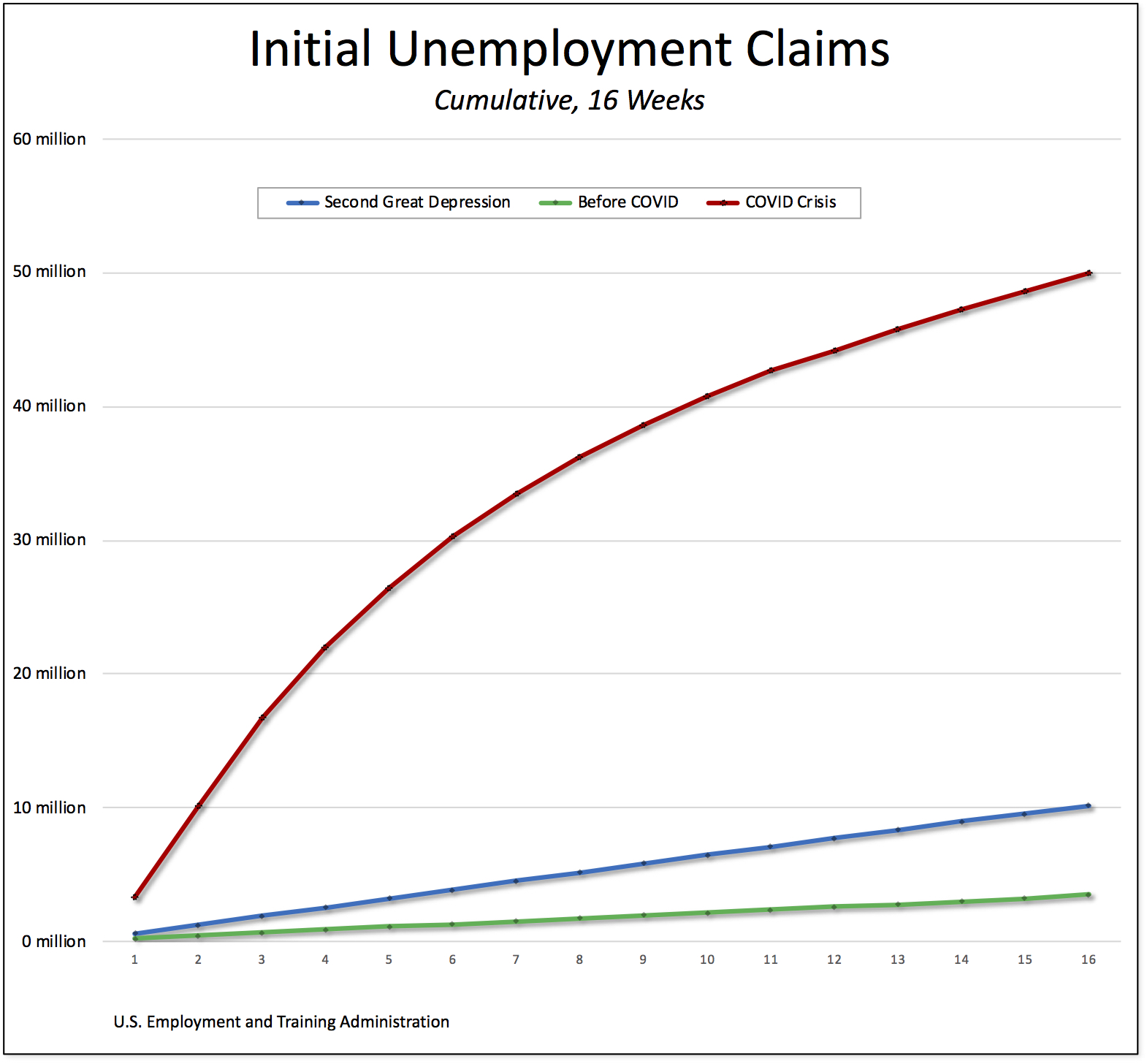

Meanwhile, what is everyone else supposed to do? Well, they have to stay as safe as they can at home and on the job—as they are subjected to the second or third wave of the pandemic—and try to obtain sufficient food, remain in their shelter while not being able to keep up with their rents and mortgages, and pay for their healthcare—in the midst of widespread pay cuts and soaring unemployment.

And, perhaps, begin to sharpen the twenty-first century equivalent of pitchforks. . .

———

*That’s my quick (and, I understand, overly simplistic) argument against the rise of fascism in the United States: billionaires and the other members of the group of ultra-wealthy individuals don’t need it, since they’re doing quite well the way things are.

**Currently, five of the largest American tech companies—Apple, Amazon, Alphabet, Facebook, and Microsoft—have market valuations equivalent to about 30 percent of U.S. gross domestic product. That’s almost double what they were at the end of 2018.