OK but if Austerity wine is $16.99, my austerity wine is still Two-Buck Chuck (now selling for $2.49).

Archive for February, 2013

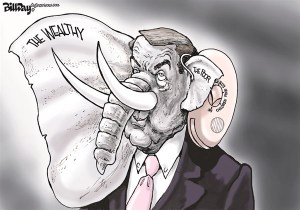

Cartoon of the day

Posted: 28 February 2013 in UncategorizedTags: banks, cartoon, crisis, debt, poor, Republicans, rich, sequestration, United States, Wall Street

Fear and loathing in the United States

Posted: 27 February 2013 in UncategorizedTags: entitlements, government, jobs, rich, United States, welfare, workers

There are two ways of responding to the charge that the poor are unjustifiably dependent on state handouts.

One is to argue that the rich are also dependent on the state. As Amia Srinivasan explains,

Conservatives champion an ethos of hard work and self-reliance, and insist — heroically ignoring the evidence — that people’s life chances are determined by the exercise of those virtues. Liberals, meanwhile, counter the accusation that their policies encourage dependence by calling the social welfare system a “safety net,” there only to provide a “leg up” to people who have “fallen on hard times.” Unlike gay marriage or abortion, issues that divide left from right, everyone, no matter where they lie on the American political spectrum, loathes and fears state dependence. If dependence isn’t a moral failing to be punished, it’s an addictive substance off which people must be weaned. . .

But if the poor are dependent on the state, so, too, are America’s rich. The extraordinary accumulation of wealth enjoyed by the socioeconomic elite — in 2007, the richest 1 percent of Americans accounted for about 24 percent of all income — simply wouldn’t be possible if the United States weren’t organized as it is. Just about every aspect of America’s economic and legal infrastructure — the laissez-faire governance of the markets; a convoluted tax structure that has hedge fund managers paying less than their office cleaners; the promise of state intervention when banks go belly-up; the legal protections afforded to corporations as if they were people; the enormous subsidies given to corporations (in total, about 50 percent more than social services spending); electoral funding practices that allow the wealthy to buy influence in government — allows the rich to stay rich and get richer. In primitive societies, people can accumulate only as much stuff as they can physically gather and hold on to. It’s only in “advanced” societies that the state provides the means to socioeconomic domination by a tiny minority. “The poverty of our century is unlike that of any other,” the writer John Berger said about the 20th century, though he might equally have said it of this one: “It is not, as poverty was before, the result of natural scarcity, but of a set of priorities imposed upon the rest of the world by the rich.”

The other, as I’ve tried to do before, is to contest the whole idea of dependence on the state.

In particular, why is selling one’s ability to work for a wage or salary any less a form of dependence than receiving some form of government assistance? It certainly is a different kind of dependence—on employers rather than on one’s fellow citizens—and probably a form of dependence that is more arbitrary and capricious—since employers have the freedom to hire people when and where they want, while government assistance is governed by clear rules. . .

While I’m at it, how are the profits that are received by private-equity companies (like Bain Capital), not to mention the multimillion-dollar payouts to CEOs, not themselves a form of dependence on the surplus created by workers in enterprises they invest in and manage? Don’t venture capitalists and other members of the 1 percent feel entitled to receive their large share of the booty society produces—and then to pay lower and lower taxes on their cut?

The limits of money

Posted: 27 February 2013 in UncategorizedTags: banks, economic representations, finance, London, money, novel

The last time I ran across John Lanchester, it didn’t go so well.

However, based on Michael Lewis’s review of Lanchester’s new novel Capital, I’ll probably give him another chance.

This is, of course, all make-believe. Lanchester controls his fictional world; there is no rule of real life that says if you spend all your time and energy trying to make a million bucks a year you are inherently phony or loathsome, just as there is no rule that says if you devote your time and energy to things other than the relentless pursuit of material gain you are inherently lovable. But in Lanchester’s fictional world, a world that feels plausible and unforced and true, even, I’ll bet, to many people who work in the City of London, the lust for money is a moral disease with an extremely high mortality rate. . .

I also found myself thinking: the English may finally have decided they have had enough of their experiment with the American financial way of life. If what happened in the Western world financial system had happened at another time in history, there would have been an obvious political response: a revolt against the Roger Younts of the world and, more generally, the grotesque inequities spawned by the putatively free financial marketplace. If the memory of British socialism wasn’t so fresh—if people didn’t still recall just how dreary London felt in 1980—they’d be pulling down the big banks, and redistributing the wealth of the bankers, and it would be hard to find a good argument to stop them from doing it. The absence of the satisfying political response to the financial crisis is due, at least in part, to the absence of an ideological vessel to put it in. No one wants to go forward in the same direction we’ve been heading, but no one wants to turn back either. We’re all trapped, left with, at best, the hope that our elites might experience some kind of moral transformation.

The English, interestingly, have been leading the way on this. Since the financial crash, the Bank of England has consistently been the main source of argument hostile to established financial interests, and made cogent cases for reducing by fiat both the size of banks and the pay of bankers. Most recently the newly elected archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby, penned an opinion piece for Bloomberg News, in which he pleaded that “financial services must serve society, and not rule it. They must be integrated into the economy, not semidetached.” And now we have a leading English novelist, and fair-minded soul, showing us the effects of the world we’ve created, or allowed to be created for us. Capital may open as a story about money, but it ends as a story of the limits of money—and with a bit of hope. In its closing line the former British investment banker has lost his job and is finally having a refreshing thought: “All he could find himself thinking was: I can change, I can change, I promise I can change change change.”

Chart of the day

Posted: 27 February 2013 in UncategorizedTags: austerity, chart, sequestration, United States

OK, two charts. . .

But they tell us the same thing: the United States is suffering from government-imposed austerity, even before the effects of sequestration hit.

Cartoon of the day

Posted: 27 February 2013 in UncategorizedTags: austerity, banks, Berlusconi, cartoon, confidence, Congress, Europe, Italy, politics, sequestration, United States

Lipstick on a pig

Posted: 26 February 2013 in UncategorizedTags: capitalism, security, wealth, work

Sure, folks can get pretty creative in cobbling together a living from various low-paying jobs, government transfer payments, and help from family and friends. But to pretend, as Ross Douthat [ht: jd] does, that the decline of decent, well-paying work for a growing part of the population represents a post-work utopia is a different thing entirely.

Douthat can put lipstick on a pig. . .but it’s still a pig.

For the most part, people have not won the freedom not to have a boss. If only that were true. Instead, they’re still in a situation where they’re forced to have the freedom to sell they’re ability to work. But they can’t. Because employers are not offering decent, well-paying jobs. And so, as an alternative, people are forced to survive on whatever they can find.

Two or three off-the-books jobs. Illegal activities. Disability payments. Gifts and loans from family members and friends.

Such people have plenty of social capital. They rely on it. What they’re missing are decent, secure livelihoods, which then allow them to receive an appropriate share of the wealth they and their fellow workers are creating.

It would be different, of course, if as a society we decided that, with the wealth we have produced, we can decrease the hours of work for everyone—on the shop floor as well as in the office, on the loading docks or out front at the cash registers. But that’s not what’s happening.

Because, as Marx explained, the possibility “to do one thing today and another tomorrow, to hunt in the morning, fish in the afternoon, rear cattle in the evening, criticise after dinner. . .without ever becoming hunter, fisherman, herdsman or critic” is predicated on the abolition of private property, that is, the creation of a communist society.

To believe otherwise is merely an attempt to to dress up recent declines in labor force participation as something other than the failure of the current organization of the economy. And the need for a very different way of deciding how and when to work—and, of course, not work.

Cartoon of the day

Posted: 26 February 2013 in UncategorizedTags: cartoon, corporations, debt, deficit, military, minimum wage, Republicans, rich, sequestration, taxes, United States

The killing prices

Posted: 25 February 2013 in UncategorizedTags: corporations, healthcare, Obamacare, United States

I don’t often recommend stories that appear in Time. But Steven Brill’s exposé of the healthcare industry in the United States is worth a careful read.

Brill sets out to answer what should be the first question of healthcare reform in the United States: why exactly are the bills so high?

What are the reasons, good or bad, that cancer means a half-million- or million-dollar tab? Why should a trip to the emergency room for chest pains that turn out to be indigestion bring a bill that can exceed the cost of a semester of college? What makes a single dose of even the most wonderful wonder drug cost thousands of dollars? Why does simple lab work done during a few days in a hospital cost more than a car? And what is so different about the medical ecosystem that causes technology advances to drive bills up instead of down?

What he finds is a “a uniquely American gold rush” on the part of corporations—both profit and nominally non-profit, from drugs through hospitals to billing services—that provide healthcare commodities that, in the end, leads to much higher prices than in other countries for results that are much less than in those countries.

According to one of a series of exhaustive studies done by the McKinsey & Co. consulting firm, we spend more on health care than the next 10 biggest spenders combined: Japan, Germany, France, China, the U.K., Italy, Canada, Brazil, Spain and Australia. We may be shocked at the $60 billion price tag for cleaning up after Hurricane Sandy. We spent almost that much last week on health care. We spend more every year on artificial knees and hips than what Hollywood collects at the box office. We spend two or three times that much on durable medical devices like canes and wheelchairs, in part because a heavily lobbied Congress forces Medicare to pay 25% to 75% more for this equipment than it would cost at Walmart.

Brill’s conclusion is that Obamacare only works around the edges of the core problem.

Put simply, with Obamacare we’ve changed the rules related to who pays for what, but we haven’t done much to change the prices we pay.

When you follow the money, you see the choices we’ve made, knowingly or unknowingly.

Over the past few decades, we’ve enriched the labs, drug companies, medical device makers, hospital administrators and purveyors of CT scans, MRIs, canes and wheelchairs. Meanwhile, we’ve squeezed the doctors who don’t own their own clinics, don’t work as drug or device consultants or don’t otherwise game a system that is so gameable. And of course, we’ve squeezed everyone outside the system who gets stuck with the bills.

We’ve created a secure, prosperous island in an economy that is suffering under the weight of the riches those on the island extract.

And we’ve allowed those on the island and their lobbyists and allies to control the debate, diverting us from what Gerard Anderson, a health care economist at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, says is the obvious and only issue: “All the prices are too damn high.”

U.S. workers are being forced to pay for increasingly high health insurance premia and healthcare prices out of their stagnant wages, while U.S. corporations are resisting paying any more out of their gross profits to purchase health insurance for their workers. Something has to give, which means going beyond Obamacare to finally create a decent, affordable healthcare system in the United States—a system in which doctors and nurses can actually do their jobs and the broad masses of people have a say in how their healthcare is provided.

Public art of the day

Posted: 25 February 2013 in UncategorizedTags: art, banks, Banksy, markets, public art, Wall Street

The controversial auction of “Slave Labour (Bunting Boy)” [ht: ja], a Banksy mural that disappeared from the wall of a north London shop in mysterious circumstances, was dramatically halted on Saturday just moments before it was due to go under the hammer.

As for the rest of the contemporary art market,

While a few high-profile crimes have brought the most egregious art world misdeeds to light, a whole host of surreptitious or underhand maneuvers – most of which are perfectly legal – remain in shadow. Notoriously unregulated, the American art market has metastasized in recent years, even as the American economy has sputtered.

And for financiers, oligarchs and other “ultra high net worth individuals”, the art world offers a spectacular two-in-one deal. In addition to reliably strong returns on investment at the very top of the market, art offers instant social prestige to people who may have already made their fortunes, sometimes in a manner not in keeping with the art world’s supposed progressive values.

At Art Basel Miami Beach this past December, several dealers publicly lamented the absence of the billionaire hedge fund manager Steven Cohen, once one of their most reliable collectors. Cohen is currently under investigation over allegations related to insider trading. The Justice Department has not pressed charges against Cohen or his firm, SAC Capital Advisors, and Cohen has always maintained that he has acted appropriately. Six employees of SAC have been convicted or pled guilty to insider trading; others have been assisting federal authorities in their investigation. . .

All of this has a direct effect on artists, and on the art they make. “The vast majority of artists are struggling, underpaid, underemployed, and under-recognized,” [artist Andrea] Fraser said. “Like the majority of workers in other fields, they feel like victims of a system over which they have no control.” Her students at UCLA, where she teaches an undergraduate course on the social and economic aspects of art, “find it pretty devastating”.