Special mention

Archive for January, 2015

Cartoon of the day

Posted: 31 January 2015 in UncategorizedTags: banks, blizzard, Dodd-Frank, inequality, Koch brothers, McDonald's, politics, poverty, snow, United States, wages, weather, workers

Whose American Dream?*

Posted: 30 January 2015 in UncategorizedTags: finances, fragility, Great Depression, households, income, inequality, Second Great Depression, spending, United States, workers

This semester, we’re once again teaching A Tale of Two Depressions. And, as in previous offerings of the course, we often touch on and return to the theme of the American Dream.

The students in the course get the clear sense that the definition of the American Dream changed during the 1920s (during the transition from small-town rural life to factories in the big cities) and that the First Great Depression turned that dream into a nightmare for most Americans. A new American Dream was, of course, created during the New Deals and the postwar period but began to unravel from the mid-1970s onward (as wages stagnated and the distribution of income and wealth became increasingly unequal).

What about now, six years into the Second Great Depression?

Well, a new report from the Pew Charitable Trusts [pdf, ht: ja] documents the fragile financial situation of many U.S. households outside the top 1 percent—and thus how far American workers are from even imagining, let alone achieving, the American Dream.

Consider the following facts:

Household incomes are dramatically volatile: in 2011, about the same percentage of Americans (a bit more than 20 percent) had to endure a 25-percent decrease in income over a two-year period as a similar increase in income. (One of the consequences is that a large percentage—a third, according to one study—who suffered a loss in income still not recovered financially when their income was measured 10 years later.)

Household spending has declined and stayed down: since the start of the recession in 2007, American households have tightened their purse strings, reducing spending by almost 9 percent. Further, the typical rebound in expenditures following recessionary periods has not occurred since the end of the latest recession. (In contrast, during the 22 years before the start of the downturn, household expenditures grew 16 percent, with 69 percent of that growth [11 percent] occurring between 1990 and 2006.)

Household spending is extremely unequal: in 2013, the top quintile’s annual spending on housing alone ($30,901) outpaced what the middle quintile spent on housing, food, and transportation combined. (In turn, the middle quintile spent nearly as much on housing as those at the bottom spent in total across these categories.)

Most households are in a precarious financial situation: Almost 55 percent of households are savings-limited, meaning they cannot replace even one month of their income through liquid savings (money in cash, checking accounts, and savings accounts). Just under half of households are income-constrained, meaning they perceive that their household spending is greater than or equal to their household income. And 8 percent are debt-challenged, which means they report debt-payment obligations that are 41 percent or more of their gross monthly income. As it turns out, seventy percent of U.S. households face at least one of these three challenges, and more than a third face two or even all three at the same time.

Clearly, the current recovery has represented a reversal of fortunes, after a short but dramatic dip, for a small minority at the top. But, for the American working-class, there has been no recovery. They find themselves as far—many of them, even farther—from the American Dream as they were before the crash of 2007-08.

*The title is a bit of a private joke. Many years ago, before email existed, I told someone by telephone the title of my upcoming talk at American University on the role of mathematics in economics. I planned to begin my presentation with a discussion of Descartes’ dream. As I walked across campus and saw the posters announcing my talk, I realized the wording of my title had been transformed. So, as we walked into the seminar room, one graduate student turned to me and asked: “Professor, what does Dr. Who have to do with the mathematization of economics?”

Cartoon of the day

Posted: 30 January 2015 in UncategorizedTags: cartoon, debt, Euro, Europe, government, Greece, money, Obama, oil, politics, Saudi Arabia, superpac, Syriza, United States

Chart of the day

Posted: 29 January 2015 in UncategorizedTags: chart, consumption, inequality, United States

As the Wall Street Journal explains,

American spending patterns after the recession underscore why many U.S. businesses are reorienting to serve higher-income households, said Barry Cynamon, of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

Since 2009, average per household spending among the top 5% of U.S. income earners—adjusting for inflation—climbed 12% through 2012, the most recent data available. Over the same period, spending by all others fell 1% per household, according to Mr. Cynamon, a visiting scholar at the bank’s Center for Household Financial Stability, and Steven Fazzari of Washington University in St. Louis, who published their research findings last year.

The spending rebound following the recession “appears to be largely driven by the consumption at the top,” Mr. Cynamon said. He and Mr. Fazzari found the wealthiest 5% of U.S. households accounted for around 30% of consumer spending in 2012, up from 23% in 1992.

Indeed, such midtier retailers as J.C. Penney , Sears and Target have slumped. “The consumer has not bounced back with the confidence we were all looking for,” Macy’s chief executive Terry Lundgren told investors last fall.

In luxury retail, meanwhile: “Our customers are confident, feel good about the economy in general and their personal balance sheets specifically,” said Karen Katz, chief executive of Neiman Marcus Group Ltd., last month. Reported 2014 revenues of $4.8 billion for the company are up from $3.6 billion in 2009.

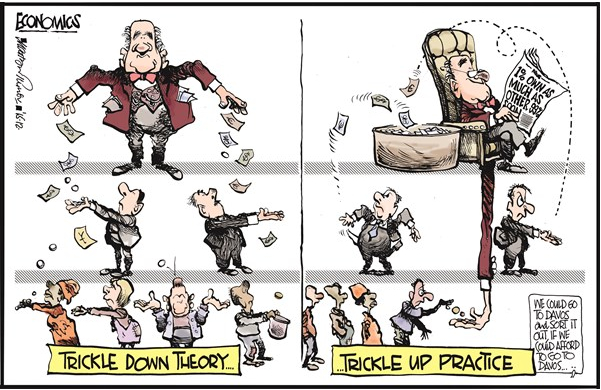

Cartoon of the day

Posted: 29 January 2015 in UncategorizedTags: 1 percent, cartoon, Davos, football, homelessness, inequality, inheritance, mental illness, taxes, trickledown, United States, work

When is a democracy not a democracy?

Posted: 28 January 2015 in UncategorizedTags: austerity, debt, democracy, Greece

If the recent Greek election was a test for austerity, which was rejected by a landslide, the current negotiations about Greek debt represents a test for democracy itself.

And the initial signs of the test for democracy are not particularly good.

A vice president of the European Commission, Jyrki Katainen, said on Wednesday that Brussels was eager to start talks with Greece. But noting that he saw no majority in favor of writing off any Greek debt, he added: “We expect them to fulfill everything that they have promised to fulfill.”

He emphasized that Brussels could not simply look at the popular anti-austerity excitement surrounding the Greek elections, but that he had to take into account the wishes of people in other countries, including Finns and Germans who were not inclined to give Greece a penny more. “We don’t change our policy according to elections,” he said.

Apparently, according to Katainen, former Prime Minister of Finland (from 2011 to June 2014) and chairperson of the National Coalition Party (from 2004 to 2014), the results of democratic elections don’t matter. Not, at least, when it comes to renegotiating Greece’s outstanding debt.

And, of course, unless Greece is able to renegotiate its debt, the vote to elect Syriza and to formulate a new set of anti-austerity policies simply won’t matter.

Honey, we shrunk the top 1 percent

Posted: 28 January 2015 in UncategorizedTags: 1 percent, chart, growth, incomes, inequality, recovery, United States

The share of total income captured by the top 1 percent actually shrunk in 2013, falling from 21.22 percent to 18.98.

But, as Emmanuel Saez [pdf] explains, that decline is probably a statistical anomaly:

The fall in top incomes in 2013 is due to the 2013 increase in top tax rates (top tax rates increased by about 6.5 percentage points for labor income and about 9.5 percentage points for capital income). The tax change created strong incentives to retime income to take advantage of the lower top tax rates in 2012 relative to 2013 and after. For high income earners, shifting an extra $100 of labor income from 2013 to 2012 saves about $6.5 in taxes and shifting an extra $100 of capital income from 2013 to 2012 saves about $10 in taxes. Realized capital gains are particularly easy to retime, explaining why the drop in top income shares in 2013 is more pronounced for series including capital gains than for series excluding capital gains.

If we take that income-shifting into account (and thus use the average of top-1 percent incomes for 2012 and 2013), we can see that, while average incomes in the United States increased (in real terms) by only 3.5 percent from 2009 to 2013 (from $53, 860 to $55,740), the average incomes of the top 1 percent soared by 24.7 percent (from $975,884 to $1,217,002).

In other words, thus far all of the gains of the so-called recovery are continuing to go to the top 1 percent.

Map of the day

Posted: 28 January 2015 in UncategorizedTags: 1 percent, inequality, map, United States

The map, from the Economic Policy Institute, indicates the thresholds to enter into the top 1 percent of income-earners. It takes, for example, $678,000 to be classified in the top 1 percent in the state of Connecticut (the highest in the nation), while $423,000 gets you into the top 1 percent in Texas.

Perhaps even more important, the data underlying the map demonstrate how lopsided economic growth has been in recent years and decades.

For example, in 2012 (the last year for which data are available), Connecticut not only had the highest 1-percent threshold in the country, it had the most unequal distribution of income: the average income of the top 1 percent was 51 times that of the bottom 99 percent. Next was New York (with a ratio of 48.4 to 1), all the way down to New Mexico (at 18.3 to 1). (For the nation as a whole, the top 1 percent took home, on average, 28.7 times as much as the bottom 99 percent.)

As for recent years, the period of so-called economic recovery (2009 to 2012), the top 1 percent captured half or more of total income growth in 40 states—in 17 of those states, the top 1 percent managed to capture all of the growth in income. In most of the rest of the states, the top 1 percent captured less than 50 percent of the income growth but still much more than their existing share of national income. (The only exceptions were Hawaii, where it was 15.3 percent, and West Virginia, where the top 1 percent share actually declined.)

As it turns out, the most recent period represents a continuation of a much longer trend. If we go back three and a half decades (to 1979), the average inflation-adjusted income of the bottom 99 percent of taxpayers grew by 18.9 percent through 2007. Over the same period, the average income of the top 1 percent of taxpayers grew by 200.5 percent. What this means is that the top 1 percent of taxpayers captured 53.9 percent of all income growth over the period. That increase occurred in the country as a whole and in every individual state. In four states, only the top 1 percent experienced rising incomes between 1979 and 2007. In another 15 states, the top 1 percent captured between half and 84 percent of all income growth from 1979 to 2007. The lowest shares of income growth captured by the top 1 percent between 1979 and 2007 was 25.6 percent (in Louisiana).

As the authors of the report conclude,

The rise in inequality experienced in the United States in the past three-and-a-half decades is not just a story of those in the financial sector in the greater New York City metropolitan area reaping outsized rewards from speculation in financial markets. While many of the highest-income taxpayers do live in states like New York and Connecticut, IRS data make clear that rising inequality and increases in top 1 percent incomes affect every state. Between 1979 and 2007, the top 1 percent of taxpayers in all states captured an increasing share of income. And from 2009 to 2012, in the wake of the Great Recession, top 1 percent incomes in most states once again grew faster than the incomes of the bottom 99 percent.

The rise between 1979 and 2007 in top 1 percent incomes relative to the bottom 99 percent represents a sharp reversal of the trend that prevailed in the mid-20th century. Between 1928 and 1979, the share of income held by the top 1 percent declined in every state except Alaska (where the top 1 percent held a relatively low share of income throughout the period). This earlier era was characterized by a rising minimum wage, low levels of unemployment after the 1930s, widespread collective bargaining in private industries (manufacturing, transportation [trucking, airlines, and railroads], telecommunications, and construction), and a cultural and political environment in which it was unthinkable for executives to receive outsized bonuses while laying off workers.

Clearly, we no longer live in such times.

Public art of the day

Posted: 28 January 2015 in UncategorizedTags: Canada, class, graffiti, public art