Special mention

Archive for January, 2018

Cartoon of the day

Posted: 31 January 2018 in UncategorizedTags: cartoon, ICE, immigrants, Jeff Sessions, KKK, racism, Stephen Miller, Trump, United States, workers

0

Cartoon of the day

Posted: 30 January 2018 in UncategorizedTags: cartoon, discrimination, guns, healthcare, LGBTQ, NRA, religion

Dystopia and global poverty

Posted: 29 January 2018 in UncategorizedTags: development, measurement, numbers, poverty, United States, world, World Bank

This post is for all those dedicated activists and teachers, such as mfa, who are committed to teaching about and creating the conditions to eliminate global poverty and economic injustice.

I have been writing of late about utopia—for example, with respect to classes and the right to be lazy.

But the world economy today represents exactly the opposite, a dystopia of extreme poverty for hundreds of millions of people (768.5 million in 2013 according to the World Bank, or 10.7 percent of the global population).

And as Angus Deaton reminds us, those struggling to survive in conditions of extreme poverty aren’t just “over there,” in the Third World. Notwithstanding the focus of the World Bank-sponsored campaign to eradicate extreme poverty and the ubiquitous appeals on behalf of the needy in poor countries, a large portion—approximately 14 million people—live in wealthy countries—some 5.3 million in the United States alone.

Is there any more damning condemnation of contemporary economic institutions, in both the North and the South?

But wait, there’s more.

We’re talking about hundreds of millions of people living—barely—on less than $1.90 a day!

That’s the official World Bank number, updated in recent years from the original $1 a day and then $1.25 a day. But let’s put that number in perspective, in order to understand how low a threshold it actually is.

First, according to recent research by Robert C. Allen (pdf), $1.90 a day for people in Third World countries covers a consumption basket of food, a variety of nonfood items, and housing. But the devil, as always, is in the details. For food, we’re talking only 2100 calories a day (enough to allow people, beyond a bare minimum, “a more ample supply of energy to do the work that sustains society as well as raising children”), plus additional food (basically animal fat and vegetables) to meet recommended daily allowances of various vitamins and minerals (iron, B12, Folate, B1, Niacin, and C). That’s it in terms of food.* It all includes various nonfood items, such as fuel, lighting, clothing, and soap—but not education, medical, and other such nonfood expenditures. Finally, a housing allowance is calculated, which amounts to just 32 square feet per person.**

Calculate the total of those expenditures (using linear programming) and you end up with an extreme poverty line for people in Third World countries of only $1.90 a day. And the way the world economy is currently organized, it can’t guarantee even that miserly sum to hundreds of millions of people across the globe.

The second way of putting that number into perspective is to recalculate it for people in wealthy countries. Allen has done that, too. For the United States, it comes out to about $4 a day (mostly because housing costs are so much higher, and make up a much larger percentage of poor people’s budgets, than in the Third World).***

That means we’re talking about just $1460 a year for an individual or $5840 for a family of four.**** The way the economy is organized in the United States forces over 5 million people to get by on less than $4 a day.

Consider what those numbers represent—whether $1.90 a day in the Third World or $4 a day in rich countries like the United States—and there’s no doubt, for hundreds of millions of people, we’re living in an economic dystopia.

*Thus, in Sri Lanka, the so-called Basic diet would consist, per person per year, of the following: 309 pounds of rice, 108 pounds of beans and lentils, 77 pounds of eggs, 9 pounds of oil, and 99 pounds of spinach, cauliflower, or peanuts).

**As even Allen admits, “By the standards of rich countries, this represents extreme, and often illegal, overcrowding. Even illegally subdivided apartments in New York offer 5–10 square meters per person.”

***In Third World countries, about two-thirds of spending is on food, one quarter on nonfoods, and 5–10 percent on housing. The food share drops to one quarter in the United States, the nonfood share remains at one quarter, and the housing share explodes to half or more of income.

****The official poverty line in the United States is $34.40 a day for an individual, which comes out to $12,752 a year. According to that standard, 43.1 million Americans (12.7 percent of the population) are forced to have the freedom to live in conditions of poverty.

Cartoon of the day

Posted: 29 January 2018 in UncategorizedTags: Amazon, Brazil, cartoon, cities, DACA, democracy, Democrats, immigration, Lula, Mitch McConnell, politics, Republicans, taxes

Cartoon of the day

Posted: 28 January 2018 in UncategorizedTags: art, cartoon, Congress, Davos, Fox News, Republicans, Trump, voters, White House

Cartoon of the day

Posted: 26 January 2018 in UncategorizedTags: Amazon, billionaires, cartoon, cities, climate change, Congress, corruption, EPA, GOP, government, politicians, Republicans

Cartoon of the day

Posted: 25 January 2018 in UncategorizedTags: cartoon, commodities, consumption, corporations, exploitation, ICE, immigrants, immigration, prisons, racism, United States

Utopia and the right to be lazy

Posted: 24 January 2018 in UncategorizedTags: automation, capitalism, history, inequality, jobs, not-work, Paul LaFargue, technology, utopia, wages, work

Students are much too busy to think these days. So, when a junior comes to talk with me about the possibility of my directing their senior thesis, I ask them about their topic—and then their schedule. I explain to them that, if they really want to do a good project, they’re going to have to quit half the things they’re involved in.

They look at me as if I’m crazy. “Really?! But I’ve signed up for all these interesting clubs and volunteer projects and intramural sports and. . .” I then patiently explain that, to have the real learning experience of a semester or year of independent study, they need time, a surplus of time. They need to have the extra time in their lives to get lost in the library or to take a break with a friend, to read and to daydream. In other words, they need to have the right to be lazy.

So does everyone else.

As it turns out, that’s exactly what Paul LaFargue argued, in a scathing attack on the capitalist work ethic, “The Right To Be Lazy,” back in 1883.

Capitalist ethics, a pitiful parody on Christian ethics, strikes with its anathema the flesh of the laborer; its ideal is to reduce the producer to the smallest number of needs, to suppress his joys and his passions and to condemn him to play the part of a machine turning out work without respite and without thanks.

And LaFargue criticized both economists (who “preach to us the Malthusian theory, the religion of abstinence and the dogma of work”) and workers themselves (who invited the “miseries of compulsory work and the tortures of hunger” and need instead to forge a brazen law forbidding any man to work more than three hours a day, the earth, the old earth, trembling with joy would feel a new universe leaping within her”).

Today, nothing seems to have changed. Workers (or at least those who claim to champion the cause of workers) demand high-paying jobs and full employment, while mainstream economists (from Casey Mulligan, John Taylor, and Greg Mankiw to Dani Rodrick and Brad DeLong) promote what they consider to be the dignity of work and worry that, even as the official unemployment rate has declined in recent years, the labor-force participation rate in the United States has fallen dramatically and remains much too low.

Mainstream economists and their counterparts in the world of politics and policymaking—both liberals and conservatives—never cease to preach the virtues of work and in every domain, from minimum-wage legislation to economic growth, seek to promote more people getting more jobs to perform more work.

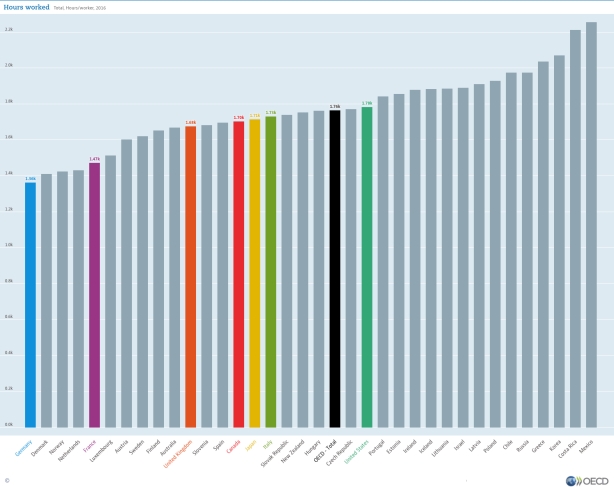

This is particularly true in the United States and the United Kingdom, where the “work ethic” remains particularly strong. The number of hours worked per year has fallen in all advanced countries since the middle of the twentieth century but, as is clear from the chart above, in comparison with France and Germany, the average has declined by much less in America and Britain.

Today, according to the OECD, American and British workers spend much more time working per year (1765 and 1675 hours, respectively) than their French and German counterparts (1474 and 1371 hours, respectively).

But in all four countries—and, really, across the entire world—the capitalist work ethic prevails. Workers are exhorted to search for or keep their jobs, even as wage increases fall far short of productivity growth, inequality (already obscene) continues to rise, new forms of automation threaten to displace or destroy a wage range of occupations, unions and other types of worker representation have been undermined, and digital work increasingly permeates workers’ leisure hours.

The world of work, already satirized by LaFargue and others in the nineteenth century, clearly no longer works.

Not surprisingly, the idea of a world without work has returned. According to Andy Beckett, a new generation of utopian academics and activists are imagining a “post-work” future.

Post-work may be a rather grey and academic-sounding phrase, but it offers enormous, alluring promises: that life with much less work, or no work at all, would be calmer, more equal, more communal, more pleasurable, more thoughtful, more politically engaged, more fulfilled – in short, that much of human experience would be transformed.

To many people, this will probably sound outlandish, foolishly optimistic – and quite possibly immoral. But the post-workists insist they are the realists now. “Either automation or the environment, or both, will force the way society thinks about work to change,” says David Frayne, a radical young Welsh academic whose 2015 book The Refusal of Work is one of the most persuasive post-work volumes. “So are we the utopians? Or are the utopians the people who think work is going to carry on as it is?”

I’m willing to keep the utopian label for the post-work thinkers precisely because they criticize the world of work—as neither natural nor particularly old—and extend that critique to the dictatorial powers and assumptions of modern employers, thus opening a path to consider other ways of organizing the world of work. Most importantly, post-work thinking creates the possibility of criticizing the labor involved in exploitation and thus of creating the conditions whereby workers no longer need to succumb to or adhere to the distinction between necessary and surplus labor.

In this sense, the folks working toward a post-work future are the contemporary equivalent of the “communist physiologists, hygienists and economists” LaFargue hoped would be able to

convince the proletariat that the ethics inoculated into it is wicked, that the unbridled work to which it has given itself up for the last hundred years is the most terrible scourge that has ever struck humanity, that work will become a mere condiment to the pleasures of idleness, a beneficial exercise to the human organism, a passion useful to the social organism only when wisely regulated and limited to a maximum of three hours a day; this is an arduous task beyond my strength.

That’s the utopian impulse inherent in the right to be lazy.

Cartoon of the day

Posted: 24 January 2018 in UncategorizedTags: Bitcoin, cartoon, climate change, DACA, environment, immigration, KKK, media, muslims, racism, Republicans, rich, tax cuts, Trump, winter