Dwight Billings—Professor Emeritus of Sociology at the University of Kentucky, preeminent scholar of Appalachia, and occasional contributor to this blog—just completed a chapter for a collection of critical responses to J. D. Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy, edited by Anthony Harkins, which will be published by West Virginia University Press. He has kindly agreed to allow me to publish extracts from his chapter in this guest post.

Once upon a time, there was “a strange land and peculiar people.”* It was a mythical place known as “Trumpalachia.” J. D. Vance, author of the best-selling book Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis, has been widely acclaimed as its foremost explorer, mapmaker, interpreter, and critic. Countless readers have turned to his book to understand the appeal of Donald Trump to white working-class voters. But Hillbilly Elegy is not a “Trump for Dummies,” nor is it an elegy for Appalachia. It’s an advertisement for capitalist neoliberalism and personal choice.

***

Vance’s main argument in Hillbilly Elegy is that Appalachians and their descendants in the Rust-Belt have been “reacting to [economic decline] in the worst possible way.” He notes that “Nobel-winning economists worry about the decline of the industrial Midwest and the hollowing out of the economic core of working whites” but more important, he contends, is “what goes on in the lives of real people when the economy goes south.” There is nothing wrong with that question of course, but Vance’s answer points in the wrong direction. In his opinion, the problem boils down simply to the bad personal choices individuals make in the face of economic decline—not to the corporate capitalist economy that creates immense profits by casting off much of its workforce or the failure of governments to respond to this ongoing crisis. The real problem, he says, is “about a culture that increasingly encourages social decay instead of counteracting it.”

Vance’s bottom line is: “Public policy can help, but there is no government that can fix these problems for us. . . These problems were not created by governments or corporations or anyone else. We created them, and only we can fix them.” Vance’s fix, the usual neoliberal fix, is fix thyself. There is of course nothing new here in Vance’s recycling of worn out culture of poverty theory. Hillbilly Elegy is the pejorative 1960s Moynihan report on the pathology of the black family in white face and a rehash of Charles Murray’s more recent Coming Apart: The State of White America, 1960-2010.

When the Wall Street Journal endorsed Hillbilly Elegy, it commended the book for its stress on the values of “religion, discipline, and family,” but chiefly lauded that fact that “most of all [Vance] wants people to hold themselves responsible for their own conduct and choices.” The stress on personal choice and accountability is a central theme in the ideology of neoliberalism. Hillbilly Elegy’s alignment with it is surely another reason for the book’s sales success.

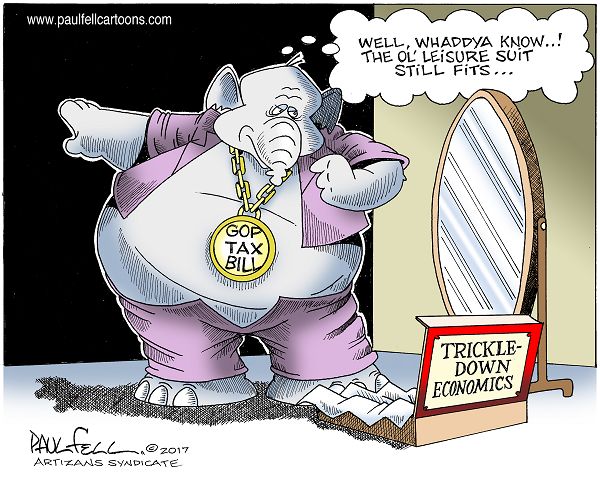

Capitalist neoliberalism encompasses a broad range of ideas, practices, and policies. Its diverse economic, political, and cultural projects promote, among other things, deregulation, privatization, the outsourcing of public services, fiscal austerity, global trade liberalization, supply-side monetarism rather than demand-side stimulation, financialization, marketization, anti-unionism, and massive taxes cuts for the superrich and corporations. At the individual level, it stresses personal responsibility for one’s own wellbeing

But wait. Things get a little more complicated. Vance isn’t saying that his hillbillies are perfect neoliberal subjects—just that they should become so. To get ahead, they must fix themselves but what holds them back is a dysfunctional ethno-regional, Scots-Irish culture. Here is where the two tracks of Hillbilly Elegy come together, or perhaps tensely collide, Vance’s personal memoir and his cultural one. One the personal level, Hillbilly Elegy is about the good choices Vance made that he believes allowed him to escape poverty. On the cultural level it is about good choices that “others in [his] neighborhood hadn’t” made because of their ethnic heritage. Never mind that the book’s premise about what Scots-Irish culture in Appalachia or elsewhere is based on stereotypes that have long been refuted, or that its demographic claim that the Scots-Irish ever constituted a majority of the Appalachian population is simply not true. Hillbilly Elegy is at once an advertisement for the neoliberal promised land of zombie-like entrepreneurial souls and an elegy for a dying but not yet dead-enough Scots-Irish regional culture that doesn’t really exist.

***

Undoubtedly, efforts to understand voters’ choice for Donald Trump led many readers and much of the mass media to Hillbilly Elegy, probably the single factor that most directly contributed to the book’s phenomenal sales. (The New York Times hailed it as one of the most important books to read for understanding the election.) Despite its ultra conservative slant—Senate Majority leader Mitch McConnell recommended it as his favorite book of 2016—many of its readers were political liberals according to an analysis in The Economist based on Amazon book sales. Readers of Hillbilly Elegy were far more likely to buy books like Mark Lilla’s Once and Future Liberal, Nancy Isenberg’s White Trash, and Arlie Russell Hochschild’s Strangers in their Own Land rather than rightwing books such as Ann Coutler’s In Trump We Trust, Eric Bolling’s The Swamp, or Mark Levin’s Rediscovering Americanism. One hundred and fifty years of stereotypes about Appalachia and elitist stereotypes about poor people as “white trash” (shown by Isenberg to date back to the early colonial era) help to explain the why liberal readers might find J. D. Vance to be a plausible guide to the current political scene as well as a analgesic for any qualms over inequality and injustice in the United States.

Appalachia became what I call “Trumpalachia,” a media-constructed mythological realm, backward and homogenous. Appalachians were still “yesterday’s people” as they were described in the 1960s, but now it seems they had grown bitter, resentful, rightwing, and racist. Its supposed “cultural issues with racism, sexism, and homophobia” took center stage in liberals’ diagnosis of its pathology. “A perfect storm of economics, creeping conservatism and outright racism” was said to have spawned its turn to the right after decades in the Democratic column. Hillbillies were said to be in despair over their “perceived and real loss of the social and economic advantages of being white.” The Guardian described them as part of “a backlash from white, working-class voters frustrated by their relative decline in status in America—symbolized, in part, of course, by its first black president.” “America is no longer white enough” for these voters wrote a New York Times columnist. “To these people, Trump’s ‘Make America Great Again’ is not the empty rhetoric of a media-savvy con artist from Queens but a last-ditch rallying cry for the soul of a changing land where minorities will be the majority by the middle of the century.” Another stated: “Let’s put this clearly, the stressor at work here is the perceived and real loss of the social and economic advantages of being white.” Above all, white Appalachia came to be represented as “a tinderbox of resentment that ignited national politics.”

Appalachian voters did of course resoundingly support Donald Trump in 2016, and like non-metropolitan voters elsewhere, for a variety of reasons. For many, Hillary Clinton’s unfortunate remark that she would put “a lot of coal miners and coal companies out of work” was decisive. But there is more to the story than this. When asked to explain why Trump was so popular in Appalachia, J. D. Vance explained: “The simple answer is that these people—my people—are really struggling, and there hasn’t been a single political candidate who speaks to those struggles in a long time. Donald Trump at least tries.”

But that’s not true. Bernie Sanders did, and he beat Hillary Clinton in every county in West Virginia and almost all the counties in Appalachian Kentucky including all its coal counties in the presidential primaries, yet the national media gave this almost no attention at all. McDowell County, West Virginia probably got more media attention than any other place because while Obama had won a majority of votes there in 2008, Trump won by 74 percent in 2016. Significantly, however, Sanders won twice as many votes as Trump in the primary election there. When he was not on the ballot, however, 73 percent of McDowell’s registered voters simply stayed home and did not vote at all. Sanders strong support suggests to me that a significant number of voters in the coalfields and the wider region were prepared to vote for a more progressive candidate in the general election had one been available, not one indebted to Wall-Street.

***

In the meantime, J. D. Vance has gone on to shore up his rightwing credentials. He has been discussed as a candidate for high political office and has established a non-profit organization in Ohio to fight “opiate abuse, save families, and create a pathway to the middle class.” Recently, he wrote the preface to the Heritage Foundation’s “2017 Index of Culture and Opportunity,” a Koch-funded reiteration of the culture of poverty thesis. In line with the Koch brothers who put their vast money behind down-ticket Republican candidates rather than Donald Trump, Vance reports that he loved but was terrified by Trump and voted for a conservative write-in candidate instead. Nevertheless, he was promoted by alt-right extremist Steve Bannon as a candidate for head of the Heritage Foundation. Vance is misguided, but he is no Steve Bannon. Given his depiction of hillbillies as a distinct race of disadvantaged white ethnics, however, it’s perhaps not surprising that Bannon, who called Hillbilly Elegy “a magnificent book,” would try to recruit him as a potential “ally.”

The top echelon of the super rich in America has never been wealthier, while the income of deeply indebted American wage earners has been stagnant for decades. Millions of people in the United States are forced to live in poverty, and millions more suffer from economic insecurity and severe hardship. Now is no time for identity politics and shibboleths about self-sufficiency and personal choice.

In “The Afterlife of a Memoir,” Aminatta Forno advises: “Write a memoir but only if you are sure you want to live with the consequences everyday for the rest of your life.” The great danger and ultimate tragedy of Hillbilly Elegy is not simply that it perpetuates Appalachian stereotypes. It is that it promotes toxic politics that will only further oppress the hillbillies that J. D. Vance professes to love and speak for.

*Appalachian readers will be familiar with the phrase “strange land and peculiar people” as an early instance of the “othering” of Appalachia. See Henry D. Shapiro, Appalachia on Our Mind (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1978).