The stock-in-trade of neoclassical economists, like Harvard’s Gregory Mankiw, is that free markets are the most efficient way of allocating scarce resources. Therefore, they spend a great deal of time celebrating free markets, and criticizing any kind of regulation of or intervention into markets.

Rent control is a good example, one that is taught to thousands of undergraduate students every semester. According to Mankiw, when governments establish price ceilings on rental housing, they cause a shortage of rental units. In the short run (as in the chart on the left above), when the supply of rental housing is fixed, the shortage may be relatively small. But in the long run (as in the chart on the right above), when both the supply of and the demand for rental housing are more “elastic” (that is, more sensitive to changes in price), the shortage grows.

When rent control creates shortages and waiting lists, landlords lose their incentive to respond to tenants’ concerns. Why should a landlord spend money to maintain and improve the property when people are waiting to get in as it is? In the end, tenants get lower rents, but they also get lower-quality housing. . .

In a free market, the price of housing adjusts to eliminate the shortages that give rise to undesirable landlord behavior.

That’s the world according to neoclassical economic theory. And in reality?

source

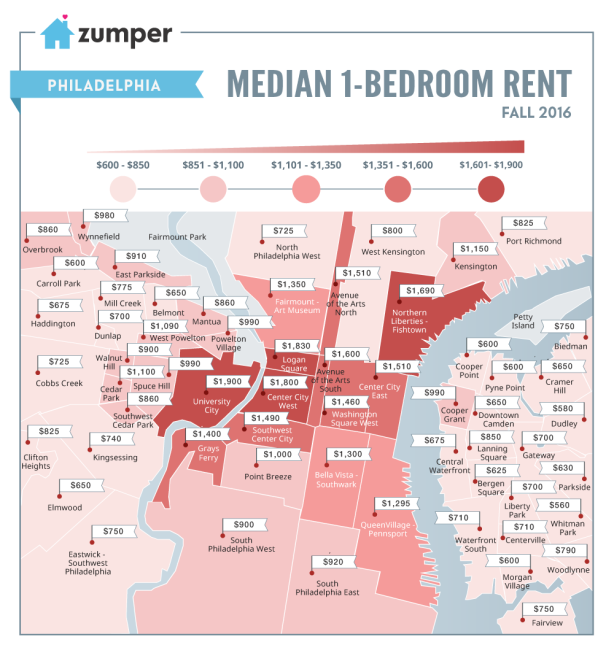

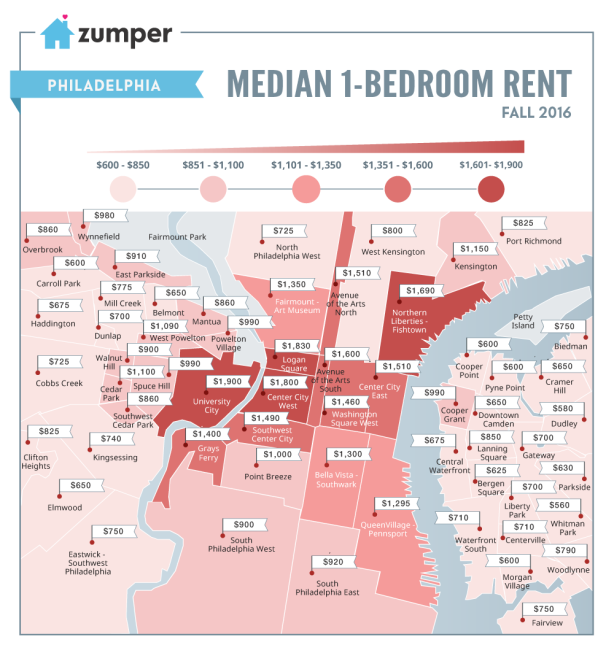

Philadelphia, the City of Brotherly Love—aka the nation’s poorest big city, and among the most racially segregated—according to Caitlin McCabe [ht: ja], “is increasingly becoming a renter’s haven.”

But what happens when too many renters, many of them higher-income, flood the market?

In cities such as Philadelphia, lower-income residents feel the squeeze. And it could be getting worse for them

A new study by the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia shows that, as a result of gentrification, Philadelphia lost one-fifth of its low-cost rental-housing stock—more than 23,000 units renting for $750 a month or less—between 2000 and 2014.

Even more, the study found, the affordable housing that remains in the city is in danger, too—

since 20 percent of the city’s federally subsidized rental units will see their affordability restriction periods expire within the next five years. Of these rental units, more than 2,300 are in gentrifying neighborhoods.

source

The short-term result of gentrification and the loss of low-cost rental housing is that Philadelphia is now the fifteenth-most-expensive rental city in the nation, with a median rent (for a one-bedroom apartment) of $1,400. In the long run, the shrinking stock of affordable housing leaves lower-income renters saddled with higher rent burdens, greater financial distress, and insecure housing arrangements, which combine to reinforce residential patterns that are already highly segregated by income and socioeconomic status.

As the Philadelphia Fed explains,

The pockets of gentrification in Philadelphia appear to reinforce these patterns in several ways. First, gentrifying neighborhoods become less accessible to lower-income movers, limiting their housing search to more distressed and less central neighborhoods. Vulnerable residents who remain in these upgrading neighborhoods often face higher housing costs and are less likely to see improvements in their financial health. In addition, vulnerable residents in neighborhoods that are in more advanced stages of gentrification may even become more likely to move out of these neighborhoods. Each of these consequences of gentrification reflects the impact of increasingly burdensome housing costs, driven by losses of both low-cost rental units and units with subsidized affordability.

The market for rental housing in Philadelphia is increasingly becoming a neoclassical economist’s dream—but a nightmare for low-income renters in the City of Brotherly Love.