The story currently being peddled by the folks at Bloomberg [ht: ja] is that the American middle-class is currently suffering, as the enormous wealth they managed to accumulate during the past few years is now dwindling. And that crisis—the end of their “once-in-a-generation wealth boom”—is what they will take into the midterm elections.

There is a kernel of truth in that story but it is overshadowed by all that it leaves out.

The small sliver of truth?

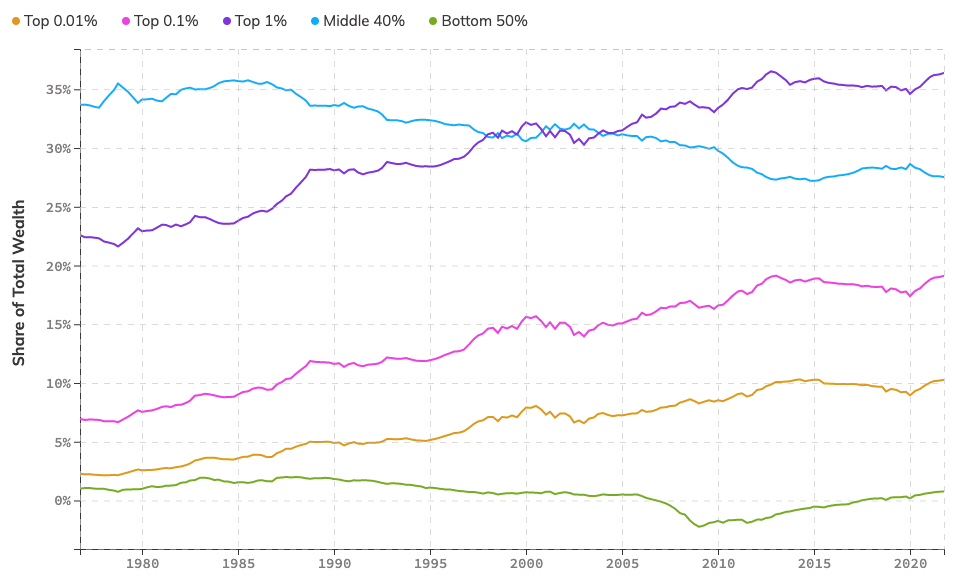

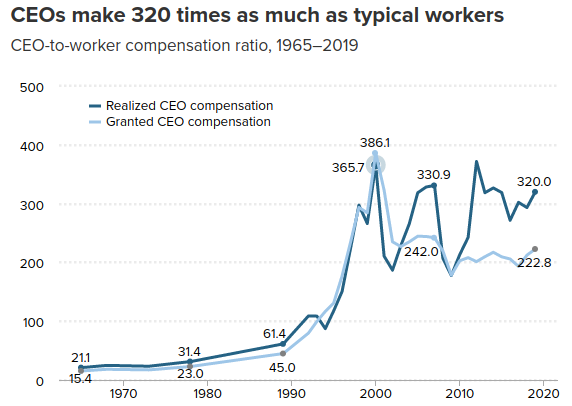

Yes, as we can see in this chart, the average real wealth (in July 2022 dollars) of the middle 40 percent of Americans did in fact increase from January 2017 (when Donald Trump first took office) until March of 2022; now it has begun to fall and is projected to continue declining (according to data provided by Realtime Inequality).*

That should come as no surprise. It is the result of years of cheap money, which has fueled increases in the value of the two major components of middle-class wealth: house prices and the stock market. Now, while the price of real estate continues to rise (as anyone knows who has attempted to purchase a house in recent months), the stock market has taken a tumble (with the Fed policy of increasing interest-rates, on top of disruptions in global supply chains and the war in Ukraine).

So, yes, middle-class wealth is falling. But that’s only part of the what is going on out there, beyond Bloomberg’s narrow lens.

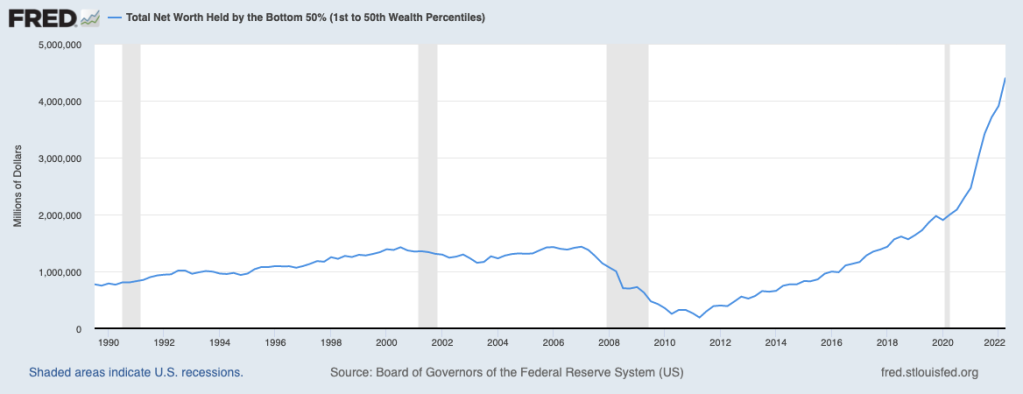

Another important part of the story, which I discussed on Wednesday, is the plight of the bottom 50 percent of American workers. Yes, their average wealth also increased during the same period but not by much more than a rounding error: a total of $13.8 thousand for each person. Their average wealth at the most recent peak reached $12 thousand, and not it too is beginning to fall.

What else is left out of the Bloomberg story? Well, it only refers to the absolute level of middle-class wealth.

As is clear from the chart above, the average wealth of the middle-class (the blue line) is much closer to that of the bottom 50 percent (the green line) than it is to the wealth of the top 1 percent (the brown line): $366.5 thousand compared to $11.9 thousand and $17.5 million, respectively. That doesn’t look like much of a bonanza to me, certainly not in relative terms.

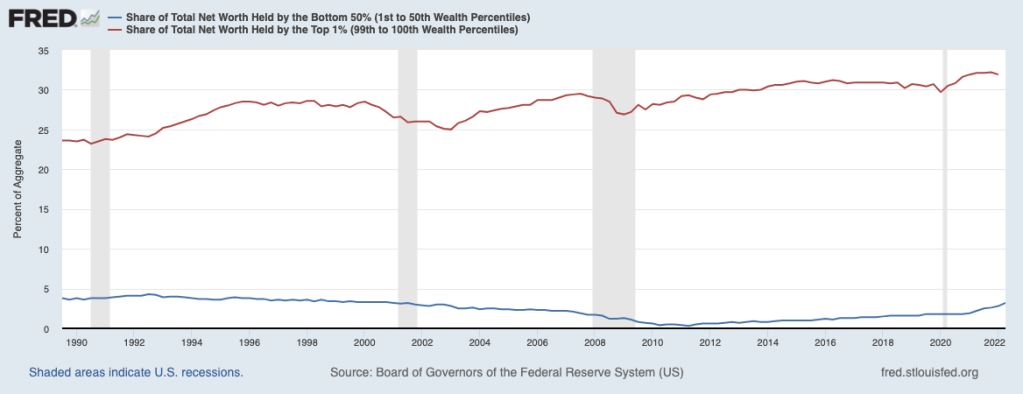

Indeed, the third major part of the missing story has to do with the changes over time in the shares of wealth owned by each of the the classes.

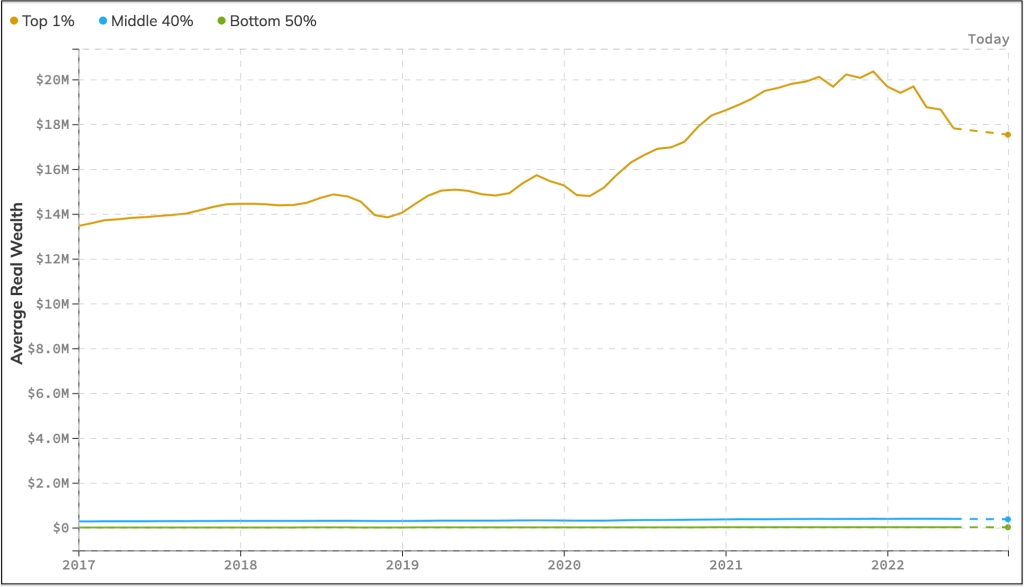

The fact is, the middle-class share of total wealth has been steadily declining since the mid-1980s (falling from 35.7 percent to 28.9 percent), while that of the entire bottom 50 percent has also decreased (from a minuscule 2 percent to a barely perceptible 1.2 percent). Meanwhile, the share of wealth owned by the top 1 percent has soared dramatically (from 21.8 percent to 34.6 percent).

If we add those three elements to Bloomberg’s story, we end up with a very different narrative about the U.S. economy. American workers—both poor and middle-class—have been losing out to those at the top for decades now.

Yes, along the way, there have been minor peaks and troughs in their accumulation of wealth (just as has been the case for those at the top) but the long-term trajectory is clear: a growing gulf between those at the top and everyone else. Under both Democratic and Republican administrations.

It’s a problem that will not be solved in this midterm election, not with the candidates and campaigns we’re seeing from both political parties.

It’s a fundamental problem with American capitalism. But that, alas, does not fit into the Bloomberg story either.

———

*The middle 40 percent is the population whose wealth falls between the 50th and 90th percentiles.