From Chile to Lebanon, young people are demonstrating—in street protests and voting booths—that they’ve had enough of being disciplined and punished by the current development model.

Last Friday, more than one million people took to the streets in the Chilean capital of Santiago, initially sparked by a sharp rise in Santiago’s metro fares and now uniting in a call for much larger economic and political change in the country.

Near-daily protests in Port-au-Prince, other cities, and the countryside have taken place for weeks now. A deepening fuel shortage in mid-September, on top of spiraling inflation, a lack of safe drinking water, environmental degradation, food scarcity, and mounting corruption have caused Haitians to block roads and highways, demanding the resignation of President Jovenel Moïse and the elite that continues to block fundamental change.

Two weeks ago, Ecuador’s president, Lenín Moreno, was forced to strike a deal with indigenous leaders to cancel a much-disputed austerity package and end nearly two weeks of demonstrations that have paralyzed the economy.

In Beirut, protesters say they are finished with their leaders, many of them former civil war-era warlords who rule the country like a series of personal fiefdoms to be plundered, dispensing the spoils to loyal followers. “We need a whole new system, from scratch,” said one protestor.

Meanwhile, voters in Argentina chose the Peronista ticket of Alberto Fernández and former president Cristina Fernández de Kirchner over incumbent President Mauricio Macri in the first round of Argentina’s presidential election on Sunday, a rejection of austerity of the sort that has sparked violent protests elsewhere in Latin America.

And, as we’ve seen, young people have been marching across the globe—to protest against the introduction of the Fugitive Offenders amendment bill by the Hong Kong government, the imprisonment of separatist leaders in Catalonia, and the climate crisis in London and around the world.

While it may be tempting to search for a single banner or theme for all these protests and movements—for example, a rejection of neoliberalism or a slowing of economic growth—we do need to pay attention to and keep in mind the specific causes, demands, and forces behind the mobilizations. As Jack Shenker reminds us,

Each of these upheavals has its own spark—a hike in transport fares in Santiago, or a proposed tax on users of messaging apps like WhatsApp in Beirut—and each involves different patterns of governance and resistance. The class composition of the indigenous demonstrators in Ecuador can’t be compared with most of those marching against the imprisonment of separatist leaders in Catalonia; nor is the state’s prohibition of protest in London on a par with the repression in Hong Kong, where officers shot live ammunition into a teenager’s chest.

(Although, truth be told, it doesn’t stop Shenker from falling into the trap of attempting to identify what he considers to be the “common threads” that “bind today’s rebellions together.”)

As it turns out, the symposium on my book, Development and Globalization: A Marxian Class Analysis, has just been published by the journal Rethinking Marxism (unfortunately behind a paywall). As I make clear in my rejoinder, I was particularly pleased that all four respondents—Eray Düzenli, Suzanne Bergeron, Jack Amariglio, and Adam Morton (who has just published a blog post on his response)—remarked on how my volume of essays on planning, development, and globalization, written over the course of three decades and published in 2011, remains relevant to the critique of political economy today.

Here, then, is the text of the pre-publication version of my rejoinder:

Changing the Subject: Response to Düzenli, Bergeron, Amariglio, and Morton

Mainstream economics cannot be salvaged. But that hasn’t stopped its practitioners from trying—in recent years, just as they have throughout the course of its history.

Sometimes, in an attempt to refurbish their approach, mainstream economists have changed the underlying theory, such as when in the late-nineteenth century they unceremoniously jettisoned the labor theory of value in favor of utility. Or when, in the 1950s, they attempted to produce a synthesis of Keynesian macroeconomics and neoclassical microeconomics. At other times, they thought the problems that bedeviled their project could be fixed by adopting and incorporating a new technique; thus, we’ve witnessed the changing enchantment with and celebration of a long line of novel (at least for mainstream economics) mathematical and statistical methods, from calculus and econometrics to linear programming and game theory. Each was supposed to stop the bleeding and, each time, it didn’t work—or, alternatively, it solved one problem and, in the process, created new ones. All the while avoiding the larger issues that have plagued mainstream economics from the very beginning.

The latest attempt to save mainstream economics and make it more “scientific” comes in the form of the much-vaunted “empirical turn”—the idea that abstract theory can and should be downplayed or set aside in favor of applied or empirically grounded analysis.[1] The celebration of this shift in mainstream research has also led to the designing of new ways of teaching economics, such as Raj Chetty’s introductory course at Harvard, “Using Big Data to Solve Economic and Social Problems” (Matthews 2019). Chetty (2013) himself has claimed, “as the availability of data increases, economics will continue to become a more empirical, scientific field.”

One of the final topics in Chetty’s course is economic development, which has been subject to salvage operations not dissimilar to the rest of mainstream economics. Since they invented it as a separate branch of economics in the postwar period (Meier 1984), mainstream development economists have sought to rescue their project by introducing new theories (from stages of growth through structuralist rigidities and lags to the existence of institutions to safeguard property rights, contracts, and markets) as well as new techniques (including planning models, input-output analysis, and cross-section growth regressions).

Development economics, like the rest of mainstream economics, has recently been transformed by the supposed turn away from theory to more applied or empirical techniques. As Abhijit V. Banerjee (2005: 4343) put it,

What is unusual about the state of development economics today is not there is too little theory, but that theory has lost its position at the vanguard: New questions are being asked by empirical researchers, but, for the most part, they are not coming from a prior body of worked-out theory.

In fact, Banerjee and his Massachusetts Institute of Technology colleague Esther Duflo (in 2011 and, soon, in 2019) have been at the forefront of this “new development economics.” Their idea is that asking “big questions” (e.g., about whether or not foreign aid works) is less important than the narrower ones concerning which particular development projects should be funded and how such projects should be organized. For this, they propose field experiments and randomized control trials—to design development projects such that people can be “nudged,” with the appropriate incentives, to move to the kinds of behaviors and outcomes presupposed within mainstream economic theory.

It is precisely this approach that has led Duflo (2017: 3) to propose that mainstream economists, especially mainstream development economists, should become more like plumbers:

The economist-plumber stands on the shoulder of scientists and engineers, but does not have the safety net of a bounded set of assumptions. She is more concerned about “how” to do things than about “what” to do. In the pursuit of good implementation of public policy, she is willing to tinker. Field experimentation is her tool of choice.

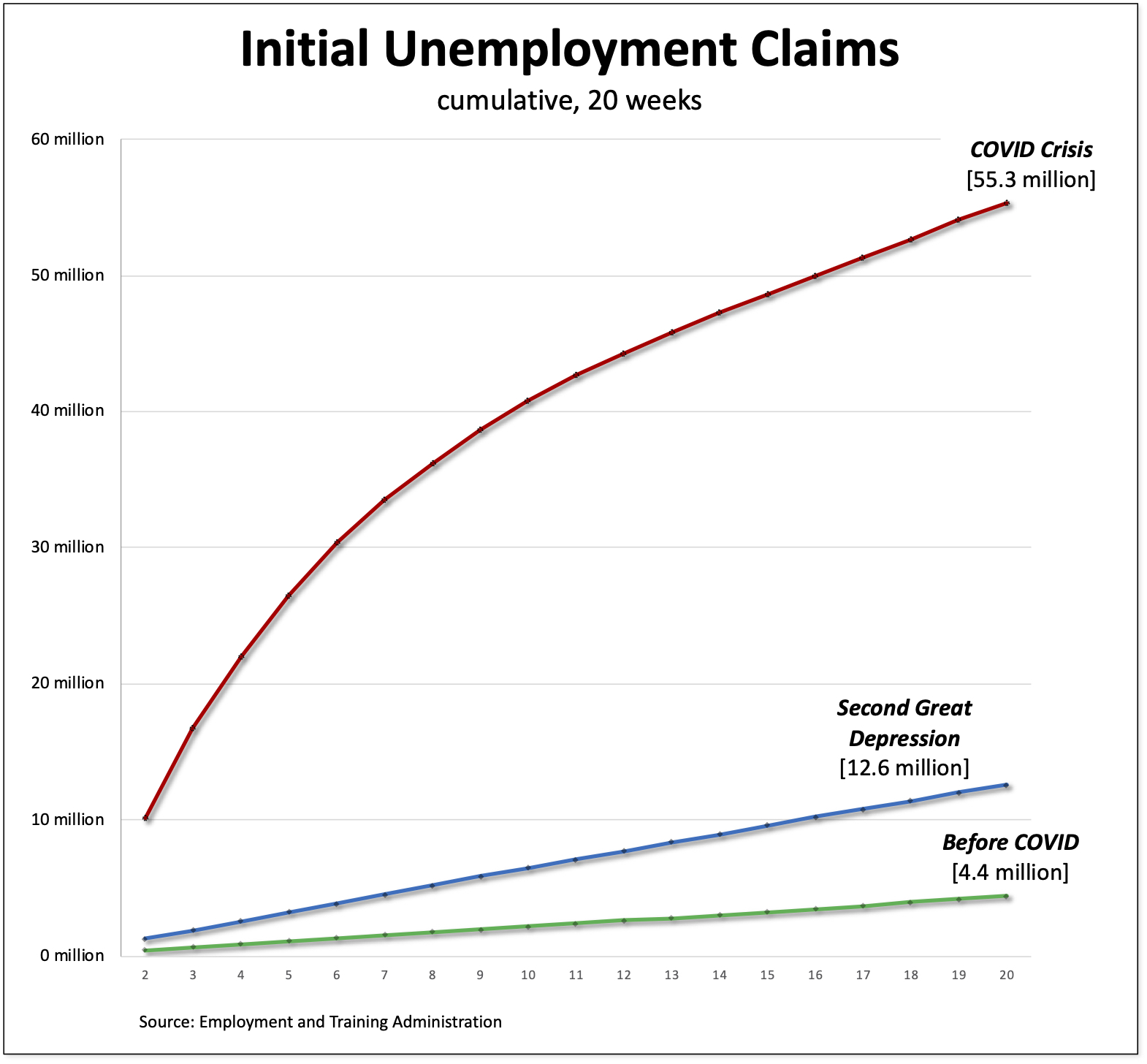

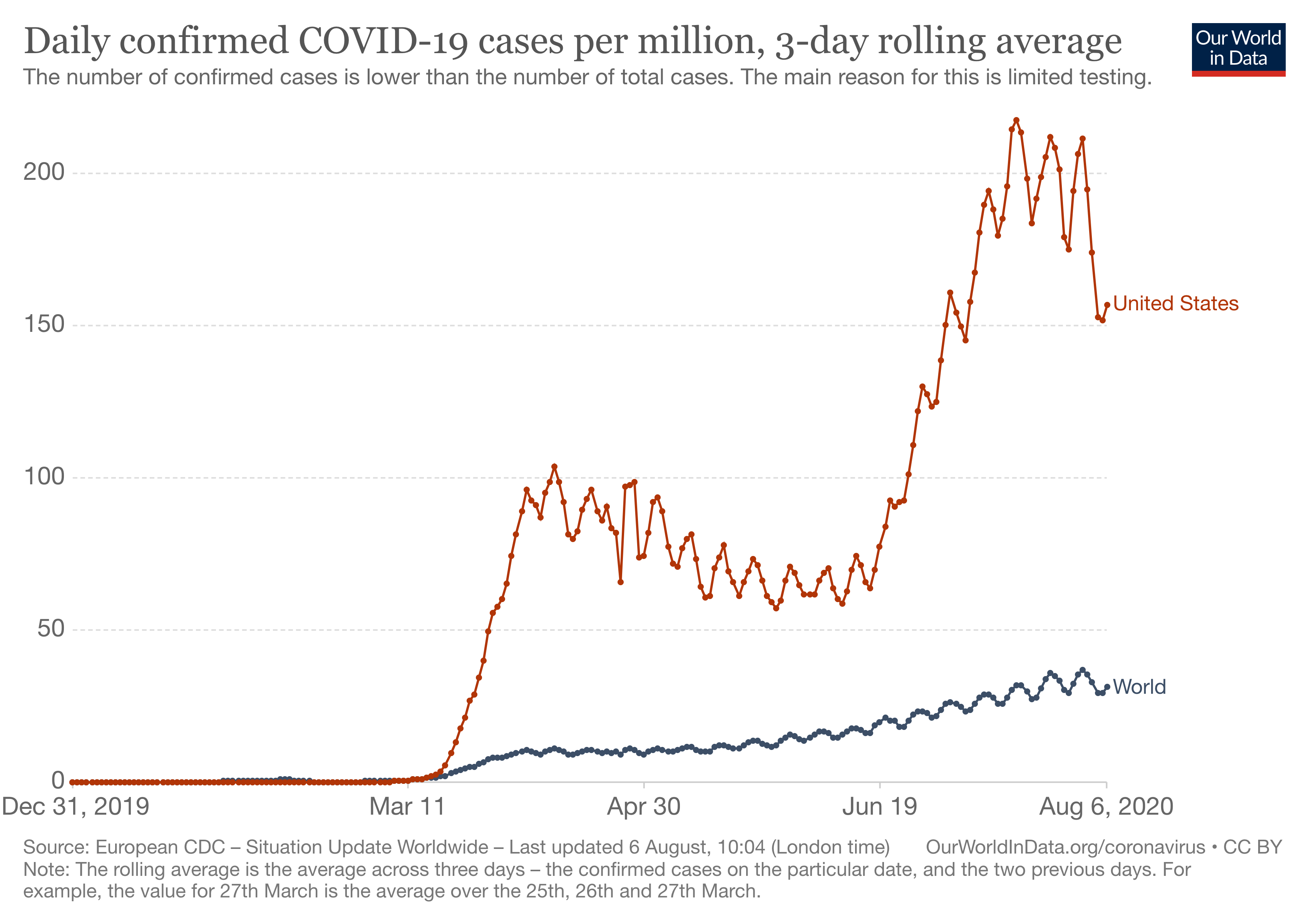

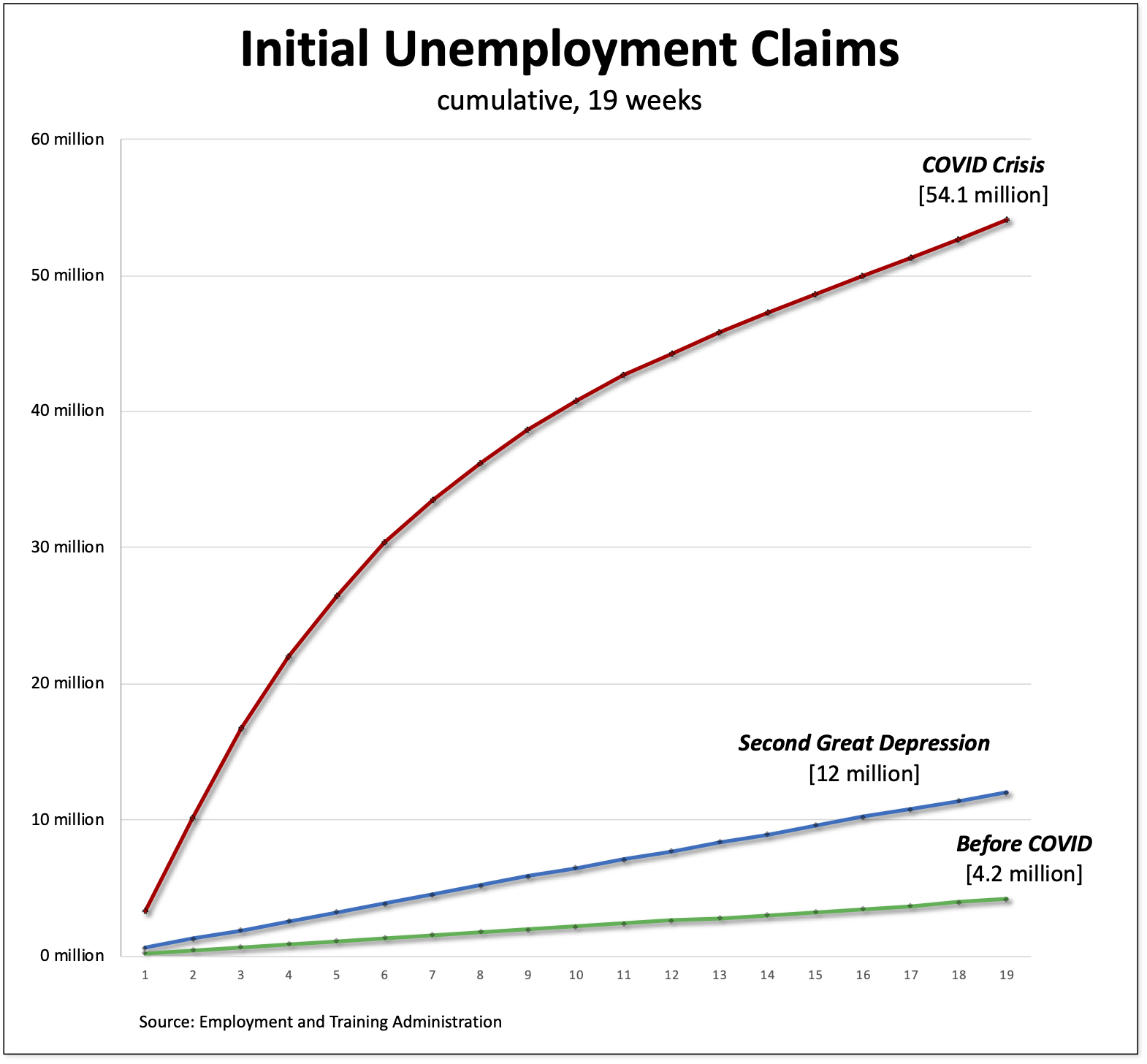

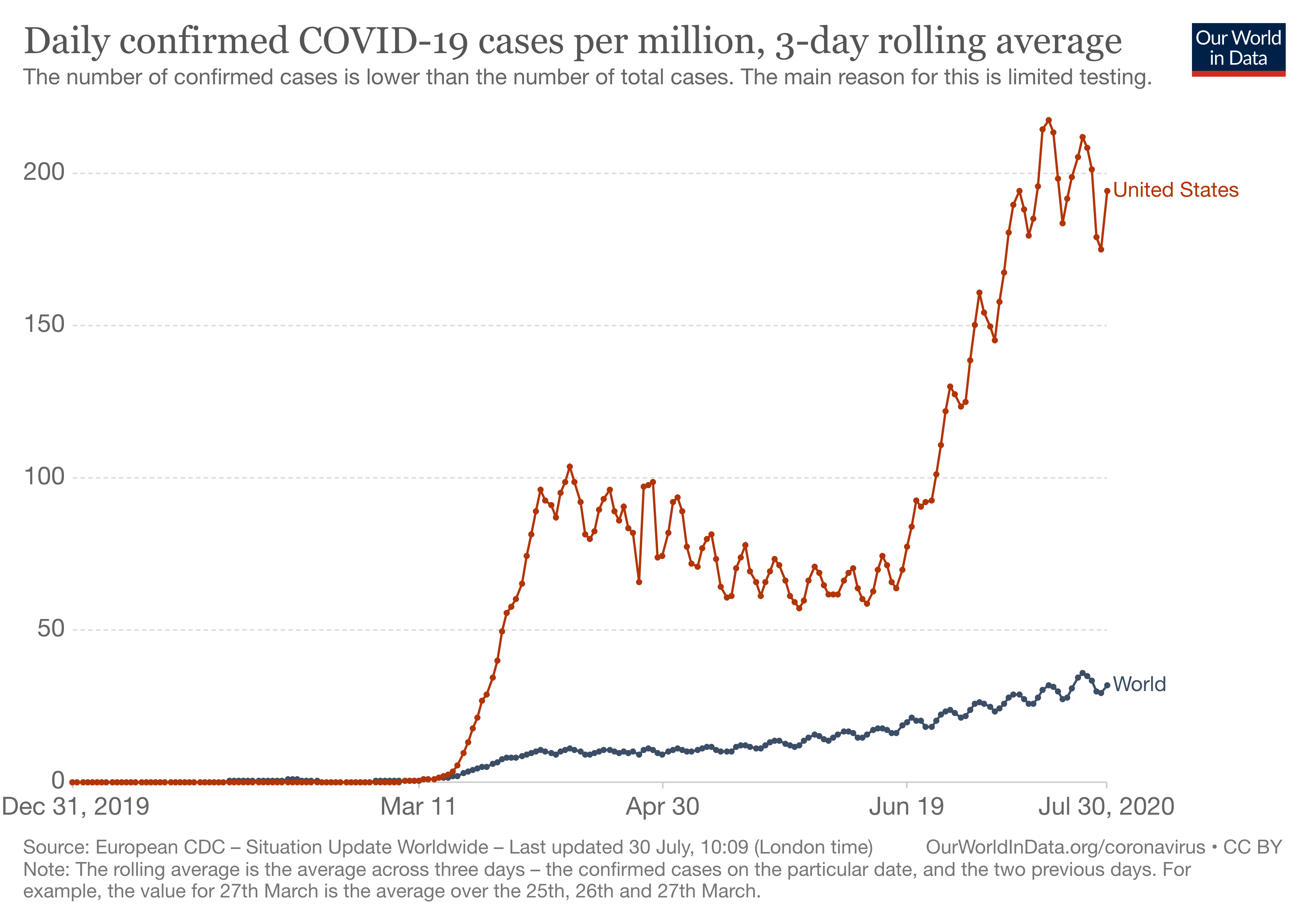

Here we are, then, in the aftermath of the Second Great Depression—in the uneven recovery from capitalism’s most severe set of crises since the great depression of the 1930s and, at the same time, a blossoming of interest in and discussion of socialism—and the best mainstream economists have to offer is a combination of big data, field experiments, random trials, and a plumber mindset. How is that an adequate response to grotesque and still-rising levels of economic inequality (World Inequality Lab 2017), precarious employment for hundreds of millions of new and older workers (International Labour Organization 2015), half a billion people projected to still be struggling to survive below the extreme-poverty line by 2030 (World Bank 2018), and the wage share falling in many countries (International Monetary Fund 2017) as most of the world’s population are forced to have the freedom to sell their ability to work to a relatively small group of employers for stagnant or falling wages? Or, for that matter, to the reawakening of the rich socialist tradition, both as a critique of capitalism and as a way of imagining and enacting alternative economic and social institutions.

If I had the opportunity to revise my book and include an additional chapter on the so-called new development economics, I would make the following points: First, the presumption that analytical techniques are neutral and the facts alone can adjudicate the debate between which development projects are successful and which are not is informed by an epistemological essentialism—in particular, a naïve empiricism—that many of us thought to have been effectively challenged and ultimately superseded within contemporary economic and social theory. Clearly, mainstream development economists ignore or reject the idea that different theories have, as both condition and consequence, different techniques of analysis and different sets of facts.

The second point I’d make is that class is missing from any of the analytical and policy-related work that is being conducted by mainstream development economists today. At least as a concept that is explicitly discussed and utilized in their research. One might argue that class is lurking in the background—a specter that haunts every attempt to “understand how poor people make decisions,” to design effective anti-poverty programs, to help workers acquire better skills so that they can be rewarded with higher wages, and so on. They are the classes that have been disciplined and punished by the existing set of economic and social institutions, and the worry of course is those institutions have lost their legitimacy precisely because of their uneven class implications. Class tensions may thus be simmering under the surface but that’s different from being overtly discussed and deployed—both theoretically and empirically—to make sense of the ravages of contemporary capitalism. That step remains beyond mainstream development economics.

The third problem is that the new development economists, like their colleagues in other areas of mainstream economics, take as given and homogeneous the subjectivity of both economists and economic agents. Economists (whether their mindset is that of the theoretician, engineer, or plumber) are seen as disinterested experts who consider the “economic problem” (of the “immense accumulation of commodities” by individuals and nations) as a transhistorical and transcultural phenomenon, and whose role is to tell policymakers and poor and working people what projects will and not reach the stated goal. Economic agents, the objects of economic theory and policy, are considered to be rational decisionmakers who are attempting (via their saving and spending decisions, their participation in labor markets, and much else) to obtain as many goods and services as possible. Importantly, neither economists nor agents are understood to be constituted—in multiple and changing ways—by the various and contending theories that together comprise the arena of economic discourse.

Changing the Subject

If those points sound familiar, it’s because they’re issues I’ve been grappling with for a long time. And I couldn’t be more pleased that, in their different ways, all four of the other participants in this symposium—Eray Düzenli, Suzanne Bergeron, Jack Amariglio, and Adam Morton—have identified, expressed their admiration for, and then rearticulated those concerns in their generous and insightful reading of the chapters on planning, development, and globalization that make up my book.[2]

Indeed, I am honored that these friends, colleagues, comrades, and former students have taken the time to work their way through my writings on those topics. I’m also flattered they found at least a few of my ideas and formulations to have merit for the ongoing and still-unsettled debates concerning capitalist development and socialist alternatives. I’m especially pleased they’ve found some of the chapters useful in the classes they teach. But, to be honest, I’m not at all surprised. In addition to their being creative and munificent thinkers in their own right, all of us have been participants in the Rethinking Marxism project. For decades now, I have had the opportunity to work with them and to learn from them in the midst of a wide variety of activities, from mundane organizational tasks to spirited intellectual discussions.[3]

Even more, I simply wouldn’t have been able to investigate and criticize the terms of debate in the areas of planning, development, and globalization without Rethinking Marxism. Partly, that’s because, while my interest in the critique of political economy (especially with respect to Latin America) long predates the existence of Rethinking Marxism, the concepts and methods utilized throughout this particular book emerged from (and, I can only hope, contributed to) the wide-ranging epistemological and methodological debates that have taken place in and around this journal. I feel fortunate to have had as my mentors Stephen Resnick and Richard Wolff and to have been inspired by the hundreds of other scholars, students, and activists who have been directly and indirectly associated with this journal.[4] It’s also because participating in the collective project of editing and producing Rethinking Marxism over the course of thirty or so years was, for me, a necessary complement to the research and writing that went into the chapters that comprise this book (not to mention the other writing projects I engaged in over the years). I know I wouldn’t have survived in the academy—especially in the all-too-often arrogant, brutish, and mind-numbing discipline of economics—without the personal relations, theoretical challenges, and collaborative labors associated with this journal.

I can’t pretend, in this limited space, to address all the interesting and important issues raised by Düzenli, Bergeron, Amariglio, and Morton in their responses. Instead, I want to focus on four themes they’ve identified and that, in my view, remain central to the project of rethinking Marxism.

Contingency of theory

Readers will have noted that all of the respondents raise the “problem of theory.” Amariglio refers to my “interest in shaping debates and altering prevailing discourses,” as defined by both mainstream economics and its heterodox (including Marxist) critics. Düzenli, for his part, notes approvingly the proposition that “the theoretical is always also political, a Marxian position.” Bergeron views the book as in the best sense a “failure,” to the extent that it does not hew “to the narrow disciplinary conventions in economics.” Finally, Morton directs attention to the importance of economic representations and the ways economic sites are “discursively produced.”

I’ll admit that I find it impossible to begin any project—whether writing or teaching—without addressing the problem of theory. That’s the case for exactly the reasons Amariglio, Düzenli, Bergeron, and Morton have mentioned: because it is important to challenge and move beyond the discursive limitations imposed by existing theories; because the different theories that structure those debates have conflicting political conditions and consequences; because the disciplinary conventions imposed by mainstream economics regulate and constrain not only the topics of discussion and debate, but also the ways those topics can be investigated; and finally because the economic landscape is socially, and especially discursively, constituted in diverse ways. Lest we forget, the lines of causality also run in the opposite direction, from the economic and social worlds to the discourses economists and others use to make sense of them, thus reinforcing the contingency of theory.

In my view, those are precisely the kinds of theoretical or epistemological concerns that are central to the Marxist critique of political economy. And they acquire particular resonance for those of us who work in and around the discipline of economics. More so than any other academic discipline, economics is structured by a hegemonic set of theories (the various and changing forms of neoclassical and Keynesian economics) that delimit what economists can and cannot say and do. Mainstream economists themselves are severely constrained by those protocols. All too often so are their heterodox critics, at least to the extent that they accept those constraints and recast their work in a manner that is different from but still runs parallel to that of their mainstream counterparts.

My own way of contributing to the project of rethinking Marxism in the areas of planning, development, and globalization has been to attend to the specificity of individual debates—at particular times, in certain countries—in order to identify their effects, challenge their limitations, and begin to elaborate an alternative way of proceeding. The reason I assembled the various essays that comprise the book was not to announce a set of lessons that pertain to all times and place, but to document a method—of concrete analysis, of ruthless criticism—that might serve as a guide for intervening in discussions and debates in other times and places.

Focusing on the contingency of theory, then, is a way of opening up spaces within particular discursive contexts so that a Marxist alternative—with its radically different theoretical and political conditions and consequences—might be articulated and new paths opened up.

Reading for class

Obviously, class is central to the book. It’s highlighted in the title, it occupies a central place in most of the chapters, and I take it to be a defining characteristic of the Marxian critique of political economy.

Readers of this journal will immediately recognize the way class is utilized in the book, especially the manner in which it is identified, discussed, and further elaborated by Düzenli, Bergeron, Amariglio, and Morton. I certainly give class a priority both in the critique of other discourses and in the various attempts to elaborate an alternative analysis. Other theories—whether in debates about markets and planning, the role of the state in both capitalist and noncapitalist forms of development, and capitalist globalization—tend to downplay or overlook the role class plays. Marxism, at least in the way I understand it, focuses precisely on the class conditions and effects that other discourses generally leave out. Moreover, class is defined in a particular manner; in the way I use it, class refers to the various circumstances whereby surplus labor is performed, appropriated, and distributed. It’s a way of building on the way Marx theorizes class across the three volumes of Capital, beginning with the theoretical “discovery” of capitalist class exploitation in the form of surplus-value—beyond the sphere in which “Freedom, Equality, Property and Bentham” rule—and proceeding to analyze how that surplus is distributed and redistributed across a formation based on the capitalist mode of production.

But, to be clear, it’s a way of “reading for class” (to use Morton’s felicitous phrase) that accords discursive but not causal priority to class. Since there is still a great deal of confusion about this formulation, let me briefly explain. When I raise the issue of class (as against other theories that either “forget about” class or define it in a very different manner), I am not suggesting that class is either the only or most important factor in determining a particular economic or social situation. That would be to attribute to class a causal priority, in a framework that looks for and necessarily then finds a ranking of determinations. I have no interest in either presuming or discovering such a causal ranking. Instead, attributing a discursive priority to class is a way of asking specifically class questions—of other theories and of the economic and social realities for which they are used to analyze.

In that sense, I was interested in finding out what the class implications were of using a particular mathematical planning model that did not “see” or use class as one of its variables. Or the class consequences of making the state the center of accumulation in revolutionary Nicaragua or concluding that one or another macroeconomic stabilization policy had failed in Peru, Argentina, and Brazil. In each case, the Marxian critique of political economy allows one to see—and, of course, then to intervene to mitigate or transform—the class effects of theories and policies that present themselves as supposedly not being about class, in either the first or last instance.

Attributing discursive priority to class is a way, then, of intervening into specific discussions and debates—and of pushing back, especially when it is declared that class (even if it once existed and perhaps was significant) has declined in importance or disappeared altogether from the economic and social landscape. No, the Marxian critique of political economy avers, here’s where class plays a role, here’s where it raises its ugly head, here’s where surplus labor is being extracted from the direct producers by an exploiting class and how it’s being distributed to still others who did not perform it. And, of course, here’s how other class arrangements can be set up whereby class exploitation is eliminated and the direct producers have a say in how and how much surplus labor takes place.

I tend to think of the discursive centrality of class as a way of adding to, rather than supplanting or subordinating, other determinations. Thus, one can ask mainstream economists, “You think introducing markets or planning to a particular situation is just a way of increasing production or consumption, well, what effects does it have on class, that is, with respect to the complex ensemble of class processes in that situation?” Or, for that matter, solving the debt crisis, carrying out a war against the U.S.-backed contras, ending apartheid, or eliminating trade barriers? Or, extending it further, what are the class implications of the theories and policies that are used to make sense of and to deal with the effects of the Second Great Depression, global warming, or for that matter a project to deliver water to poor households in Tangier?[5]

The goal is to add class to the mix, especially when other theories and policies represent determined efforts to keep the discussion as far away from class as possible.

Subjectivity

If the centrality of class is apparent on the surface of the book, then subjectivity is a strong undercurrent. And I couldn’t be more pleased that the respondents, particularly Amariglio and Bergeron, chose to focus their discussion on that theme.

Mainstream economics has, from the very beginning, presumed a given, homogenous conception of subjectivity—of both economists and the agents that populate mainstream economic theories and models. Economists are taken to be scientists (or, alternatively, engineers or plumbers) who use a singular method to arrive at disinterested theoretical and empirical conclusions and policy recommendations. That is supposed to be their singular identity. Similarly, economic agents are assumed to be characterized by and to follow the behaviors contained within and implied by an essential human nature. For example, Adam Smith (22) claimed humans have an innate desire to “truck, barter, and exchange one thing for another” (from which he derived the social and technical divisions of labor and much else); today, mainstream economists maintain that view (evident in the presumption, without any further explanation, of supply and demand schedules in markets), to which they have added self-interested utility-maximization (such that all individuals always desire more commodities, more goods and services, for themselves).

In my view, an underappreciated dimension of the Marxian critique of political economy is its radical rejection of the notion of subjectivity held by mainstream economists. There is no essential human nature; instead, subjectivity is conceived to be historically and socially produced. And there is no singular identity but, rather, multiple and changing identities over time and in any particular situation.

The critique of the mainstream view of subjectivity begins, as I have explained elsewhere (Ruccio 2014), with Marx’s discussion of commodity fetishism:

The existence of commodity exchange is not based on the essential and universal human rationality assumed within mainstream economics from Adam Smith to the present. Nor can the cultures and identities of commodity-exchanging individuals be derived solely from economic activities and institutions. Rather, commodity exchange both presumes and constitutes particular subjectivities–forms of rationality and calculation–on the part of economic agents.[6]

And, we need to add, in a society characterized by commodity exchange, other identities, including communal subjectivities, are also produced (as I argued in 1992).

My aim in the book was to build on this approach and to interrogate the givenness and homogeneity of the subjectivities presumed within mainstream economists. Thus, I sought to challenge the idea of expertise (particularly that of socialist planners), the existence of a “state subject” (e.g., in socialist planning theory and in revolutionary Nicaragua), of the essential notions of “workers” and “peasants” (especially in Nicaragua when, in the midst of war, austerity was imposed), the disinterested role of intellectuals (most notably in the case of the anti-apartheid thinker/activist Harold Wolpe), and the homogenizing effects of globalization (in favor of the hybridity of local, national, and global subjectivities).

I admit, those specific interventions represent only the first steps in challenging mainstream economists’ conception of subjectivity and opening up a space to think through the production and reproduction of multiple and changing identities—within capitalism and in terms of creating the conditions of existence of socialism. Still, they serve as a reminder that, within the Marxian tradition, subjectivities cannot be reduced to class (or, for that matter, that even class identities cannot be read off the presumed logics of class positions). And they force us to confront the subjectivities of economists (and other so-called experts), which are often obscured by reference to science or common sense. From a Marxian perspective, their identities are constituted by the discourses that interpellate them, forcing them to speak and write like mainstream economists and to attack or ignore heterodox (including Marxian) pronouncements and policies. At the same time, their theories and policies play a performative role in the economy and wider society—perhaps especially when they presume that economic knowledge is out of the reach of ordinary people and needs to be left to them, the so-called experts.

Conjuncture

The Second Great Depression occasioned a resurgence of interest in Marxian theory—because of the spectacular failures of capitalism and of the economic theories that celebrate capitalism, and consequently as a result of the search for alternative ways of organizing the economy and wider society and for theories that might help pave the way for those alternatives. That has given many of us, whom mainstream thinkers inside and outside economics have attempted to discipline and punish for decades, new platforms for teaching, speaking, and writing. However, too many of the versions of Marxian theory that have been invoked, by both mainstream economists and pundits and Marxists themselves, have been characterized by deterministic logics and modernist protocols of analysis that mimic those of mainstream economics.

The method of those versions relies on identifying and spelling out the implications of inexorable logics and underlying laws of motion of capitalism. A good example is the accumulation of capital, a central concern of Marx’s critique of political economy in chapter 24 of volume one of Capital. Except, as I have explained elsewhere (Ruccio 2018b), the famous passage that begins with “Accumulate, accumulate! That is Moses and the prophets!” is actually not Marx’s theory of capitalism, but a central tenet of classical political economy, which “takes the historical function of the capitalist in bitter earnest.”[7] In fact, Marx shows, the accumulation of capital—the use of surplus-value for purchasing new means of production, raw materials, and additional labor power—is but one of many possible distributions of surplus-value. So, there’s no necessity for the accumulation of capital—it is up to the whim and whimsy of individual capitalists, if and when they will accumulate capital—and there are many other uses for that surplus, such as distributing a portion of those profits to all the others who share in the “booty” (such as corporate chief executive officers whose incomes are over 300 times the average U.S. worker’s wage and the bankers on Wall Street whose risky decisions instigated the crash of 2007-08).

In my view, then, there’s no necessity for the accumulation of capital and, in general, no necessary laws of motion of capitalism. If we set aside and move beyond that approach to Marxian analysis, what we’re left with is a method (or what I prefer to call, influenced by Paul Feyerabend [2010], an anti-method) of “ruthless criticism” and conjunctural analysis. In that vein, I was pleased to read Amariglio’s observation that “it is the radical, Althusserian notion of ‘conjuncture’ that threads together the entire book.”

Ruccio’s conjuncture-bound essays, perhaps paradoxically, tend to stick with us. These are the kind of Marx-inspired conjunctural writings that are the most useful and meaningful to the majority of readers, writers, and activists (they are “practical,” in that sense). Ruccio’s essays stick with us because they do not pretend to be written from an eternalist or even universalist, transcendental perspective; the lessons Ruccio wishes to convey are not about forever “laws of motion” or a ubiquitous “dynamic” of an ironclad (one might say, iron-caged) capitalist economy. To the contrary, Ruccio’s essays are steeped in “current analysis” and never lazily settle on “capitalism” as forever and anon lapping the exact same oceanic ebbs and tides. That endlessly-recursive, mesmeric rendition of capitalism-as-same—whether in old-style Marxian orthodoxy or newer-style ‘late capitalist’ totalizations—here sleeps with the fishes.

But, I was not surprised to learn, that endorsement also comes with a challenge: what should we make of the current rise of far-right-wing nationalism across the globe, in countries as distinct as Turkey, Hungary, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Brazil. I couldn’t agree more with Amariglio that the attempt to subsume all these diverse occurrences as examples of “neoliberal fascism” or some such “essentially suspends conjunctural analysis by reassuring us that, really, we’ve all been here before.”

This is not the place to offer a Marxian conjunctural analysis of the backward-looking, authoritarian, racist pronouncements and policies of the leaders and members of these diverse movements. In recent years, I’ve attempted to produce some of the elements of that analysis on my blog, including a critique of contemporary mainstream economics for having paved the way for the rise of the new right-wing populisms (Ruccio 2017). But, needless to say, much more needs to be done to make sense of these developments, in their historical specificity—especially, from a Marxian perspective, of their particular class conditions and effects in the current conjuncture.

If my book serves as a guide for such an analysis, even as it determinately fails to offer a general method, it may provide at least some concrete examples of what can be accomplished based on the contingency of theory, reading for class, subjectivity, and conjunctural analysis—in other words, with ideas associated with the rethinking of Marxism. The goal, of course, is to change the subject, and thus to contribute to the project of imagining and creating alternative class possibilities and of building twenty-first century socialism.

Acknowledgments

I owe a very large debt to Eray Düzenli for organizing the session on my book at the 2013 Rethinking Marxism conference (Surplus, Solidarity, Sufficiency, at the University of Massachusetts Amherst) that has turned into this symposium. I also want to thank Chizu Sato for all her work in procuring the papers from the commentators to be part of the symposium. And finally, I am indebted to Rethinking Marxism’s new coeditors, Yahya Madra and Vincent Lyon-Callo, for their patience and understanding in extending the deadline for my rejoinder.

Notes

[1] Daniel Hamermesh (2013) is one among many who has argued that today top journals in economics—in other words, the leading journals in mainstream economics—“are publishing many fewer papers that represent pure theory, regardless of subfield, somewhat less empirical work based on publicly available data sets, and many more empirical studies based on data collected by the author(s) or on laboratory or field experiments.” Like Beatrice Cherrier (2016), I find the current celebration of the “empirical turn” to be both oversimplified and mischaracterized, since it misses previous episodes of empirical work within mainstream economics (going back to Wesley Clair Mitchell on business cycles in the 1920s). In my view, it also overlooks the role mainstream economic theory continues to play in setting and defining the agenda of empirical research.

[2] The title of the book was supposed to be “Planning, Development, and Globalization: Essays in Marxian Class Analysis,” but Routledge had already used the shorter placeholder title to list the book and at that point it couldn’t be changed.

[3] The same is true of the coauthors of some of the chapters in the book, including Stephen Resnick, Richard Wolff, the late Julie Graham, Kath Gibson, and Serap Kayatekin.

[4] I have attempted to express at least a portion of the immense debt I owe to Resnick and Wolff in two essays previously published in this journal: “Contending Economic Theories: Which Side Are You On?” (2015) and “Chance Encounters” (2018a). I also want to take the occasion to express my gratitude to my late friend and colleague Joseph Buttigieg, from whom I learned many things, including Antonio Gramsci’s philological method—which “requires minute attention to detail” and “seeks to ascertain the specificity of the particular” and, while it establishes complex networks of relations among the details, eschews any attempt to permanently fix those relations, thus avoiding the “danger of becoming crystallized into dogmas” (Buttigieg 1992, 63).

[5] Permit me, if you will, two other examples. Some years ago, I was asked to teach a course on the political economy of war and peace by the Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies. At the time, the discussion was dominated by Paul Collier’s research on greed grievance with respect to resources. With very few exceptions (e.g., Cramer 2003), there was nothing in the literature about class, which of course made it difficult to discuss either the class causes of war or the class conditions of peace. Much the same holds with respect to health care. There is growing concern in the United States that inequality in health outcomes is rising along with the grotesque and still-growing disparities in income and wealth (Zimmerman and Anderson [2019]). However, in contrast to other countries, such as the United Kingdom (which has issued a series of reports over the years on the relationship between health and class, including the Acheson Report, fully titled the Independent Inquiry into Inequalities in Health Report, in 1998), the United States does not collect health data by class. That, of course, makes it impossible to analyze the relationship between class and health, in terms of either the current situation or improved health outcomes.

[6] This interpretation of commodity fetishism relies on the pathbreaking work of Jack Amariglio and Antonio Callari (1993).

[7] This reinterpretation of the role of the accumulation of capital in the Marxian critique of political economy is due to the pioneering work of Bruce Norton (1988), which was published early on in this journal.

References

Acheson, D. 1998. Independent Inquiry into Inequalities in Health Report. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/265503/ih.pdf.

Amariglio, J. and A. Callari. 1993. “Marxian Value Theory and the Problem of the Subject: The Role of Commodity Fetishism.” In Fetishism as Cultural Discourse, ed. E. Apter and W. Pietz, 186-216. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Banerjee, A. V. 2005. “‘New Development Economics’ and the Challenge to Theory.” Economic and Political Weekly 40 (40): 4340-44.

Banerjee, A. and E. Duflo. 2011. Poor Economics: A Radical Rethinking of the Way to Fight Global Poverty. New York: PublicAffairs.

———. 2019. Good Economics for Hard Times. New York: PublicAffairs.

Buttigieg, J. A. 1975. “Introduction.” In Prison Notebooks, volume 1. New York: Columbia University Press.

Cherrier, B. 2016. Is There Really an Empirical Turn in Economics? Institute for New Economic Thinking, 29 September. https://www.ineteconomics.org/perspectives/blog/is-there-really-an-empirical-turn-in-economics.

Chetty, R. 2013. “Yes, Economics Is a Science.” New York Times, 20 October. https://www.nytimes.com/2013/10/21/opinion/yes-economics-is-a-science.html

Christopher C. 2003. “Does Inequality Cause Conflict?” Journal of International Development 15 (May): 397-412.

Duflo, E. 2017. “The Economist as Plumber.” American Economic Review 107 (5): 1-26.

Feyerabend, P. 2010. Against Method: Outline of an Anarchistic Theory of Knowledge. 4th ed. New York: Verso Books.

Hamermesh, D. S. 2013. “Six Decades of Top Economics Publishing: Who and How?” Journal of Economic Literature 51 (1): 162-72.

International Labour Organization. 2015. World Employment and Social Outlook: The Changing Nature of Jobs. Geneva: International Labour Organization.

International Monetary Fund. 2017. “Understanding the Downward Trend in Labor Income Shares.” In World Economic Outlook: Gaining Momentum? Washington, D.C.: International Monetary Fund.

Matthews, D. 2019. “The Radical Plan to Change How Harvard Teaches Economics.” Vox, 22 May. https://www.vox.com/the-highlight/2019/5/14/18520783/harvard-economics-chetty.

Meier, G. M. 1984. “The Formative Period.” In Pioneers in Development, ed. G. M. Meier and D. Seers, 3-22. New York: Oxford University Press.

Norton, B. 1988. “The Power Axis: Bowles, Gordon, and Weisskopf’s Theory of Postwar U.S. Accumulation.” Rethinking Marxism 1 (3): 6-43.

Ruccio, D. F. 1992. “Failure of Socialism, Future of Socialists?” Rethinking Marxism 5 (Summer): 7-22

———. 2014. “Capitalism.” Keywords for American Cultural Studies, ed. B. Burgett and G. Hendler, 37-40. New York: New York University Press.

———. 2015. “Contending Economic Theories: Which Side Are You On?” Rethinking Marxism 27 (2): 273-81.

———. 2017. “Populism and Mainstream Economics.” Occasional Links & Commentary on Economics, Culture, and Society, 2 March. https://anticap.wordpress.com/2017/03/02/populism-and-mainstream-economics/.

———. 2018a. “Chance Encounters.” Rethinking Marxism 30 (1): 84-95.

———. 2018b. “Strangers in a Strange Land: A Marxian Critique of Economics.” In Marxism without Guarantees: Economics, Knowledge, and Class, ed. R. Garnett, T. Burczak, and R. McIntyre, 43-58. New York: Routledge.

Smith, A. 2003 (1776). The Wealth of Nations. Intro. A. B. Krueger. New York: Bantam Dell.

World Bank. 2018. Poverty and Shared Prosperity 2018: Piecing Together the Poverty Puzzle. Washington, D.C.: World Bank.

World Inequality Lab. 2017. World Inequality Report 2018. https://wir2018.wid.world/files/download/wir2018-full-report-english.pdf

Zimmerman, F. J. and N. W. Anderson. 2019. “Trends in Health Equity in the United States by Race/Ethnicity, Sex, and Income, 1993-2017.” JAMA Network Open 2 (6): 1-10.