In this post, I continue the draft of sections of my forthcoming book, “Marxian Economics: An Introduction.” This, like the previous post, is for chapter 1, Marxian Economics Today.

A Tale of Two Capitalisms

Marxian economists recognize, just like mainstream economists, that capitalism has radically transformed the world in recent decades, continuing and in some cases accelerating long-term trends. For example, the world has seen spectacular growth in the amount and kinds of goods and services available to consumers. Everything, it seems, can be purchased either in retail shops, big-box stores, or online. And, every year, more of those goods and services are being produced and sold in markets.

That means the wealth of nations has expanded. Thus, technically, Gross Domestic Product per capita has risen since 1970 in countries as diverse as the United States (where it has more than doubled), Japan (more than tripled), China (almost ten times), and Botswana (where it has increased by a factor of more than 22).

International trade has also soared during the same period. Goods and services that are produced in once-remote corners of the world find their way to customers in other regions. Both physical commodities— such as smart phones, automobiles, and fruits and vegetables—and services—like banking, insurance, and communications—are being traded on an increasing basis between residents and non-residents of national economies. To put some numbers on it, merchandise trade grew from $318.2 billion dollars in 1970 to $19.48 trillion in 2018. And exports of services have become a larger and larger share of total exports—for the world as a whole (now 23.5 percent, up from 15 percent) and especially for certain countries (such as the United Kingdom, where services account for about 45 percent of all exports, and the Bahamas, where almost all exports are services).

The world’s cities are the hubs of all that commerce and transportation. It should come as no surprise that the urbanization of the global population has also expanded rapidly in recent decades, from about one third to now over half. In 2018, 1.7 billion people—23 per cent of the world’s population— lived in a city with at least 1 million inhabitants. And while only a small minority currently reside in cities with more than 10 million inhabitants, by 2030 a projected 752 million people will live in so-called megacities, many of them located in the Global South.

We’re all aware that, during recent decades, many new technologies have been invented—in producing goods and services as all well as in consuming them. Think of robotics, artificial intelligence, and digital media. And, with them, new industries and giant firms have emerged and taken off. Consider the so-called Big Four technology companies: Amazon, Google, Apple, and Facebook. They were only founded in the last few decades but, as they’ve continued to grow, they’ve become intertwined with the lives of millions of companies and billions of people around the world.

The owners of those tech companies are, to no one’s amazement, all billionaires. When the first Forbes World Billionaires List was published in 1987, it included only 140 billionaires. Today, they number 2825 and their combined wealth is about $9.4 trillion. That works out to be about $3,300,000,000 per billionaire. Their wealth certainly represents one of the great success stories of capitalism in recent decades.

Finally, capitalism has grown in more countries and expanded into more parts of more countries’ economies over the course of the past 40 years. Both large countries and small (from Russia, India, and China to El Salvador, Algeria, and Vietnam) are more capitalist than ever before. As we look around the world, we can see that the economies of rural areas have been increasingly transformed by and connected to capitalist ways of producing and exchanging goods and services. Global value chains have incorporated and fundamentally altered the lives of millions and millions of workers around the world. Meanwhile, areas of the economy that had been formerly outside of capitalism—for example, goods and services provided by households and government—can now be bought and sold on markets and are the source of profits for a growing number of companies.

But, unlike mainstream economists, Marxists recognize that capitalism’s extraordinary successes in recent decades have also come with tremendous economic and social costs.

All that new wealth of nations? Well, it’s been produced by workers that receive in wages and salaries only a portion of the total value they’ve created. The rest, the surplus, has gone to those at the top of the economic pyramid. So, the distribution of income has become increasingly unequal over time—both within countries and for the world economy as a whole.

According to the the latest World Inequality Report, income inequality has increased in nearly all countries, especially in the United States, China, India, and Russia. In other countries (for example, in the Middle East, sub-Saharan Africa, and Brazil), income inequality has remained relatively stable but at extremely high levels.

At a global level, inequality has also worsened. Thus, for example, the top 1 percent richest individuals in the world captured more than twice as much of the growth in income as the bottom 50 percent since 1980. Basically, the share of income going to the bottom half has mostly stagnated (at around 9 percent), while the share captured by the top 1 percent has risen dramatically (from around 16 percent to more than 20 percent).

And it’s no accident. Inequality has increased because the surplus labor performed by workers, in both rich and poor countries, has not been kept by them but has gone to a small group at the top of the national and world economies.

So, we really are talking about a tale of two capitalisms: one that is celebrated by mainstream economists (but only benefits those in the top 1 percent) and another that is recognized by Marxian economists (who emphasize the idea that the growing wealth of nations and increasing inequality are characteristics of the same economic system).

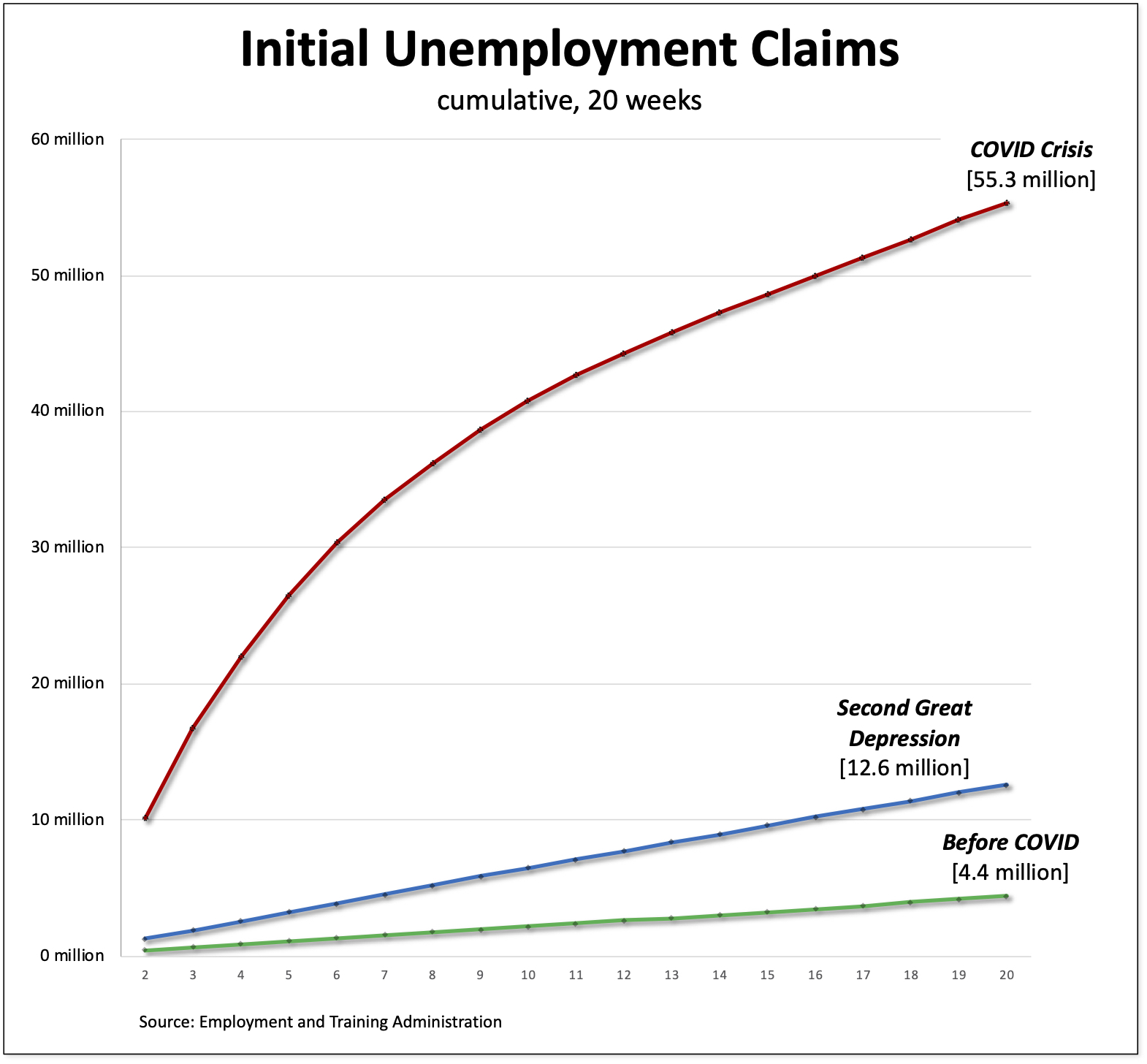

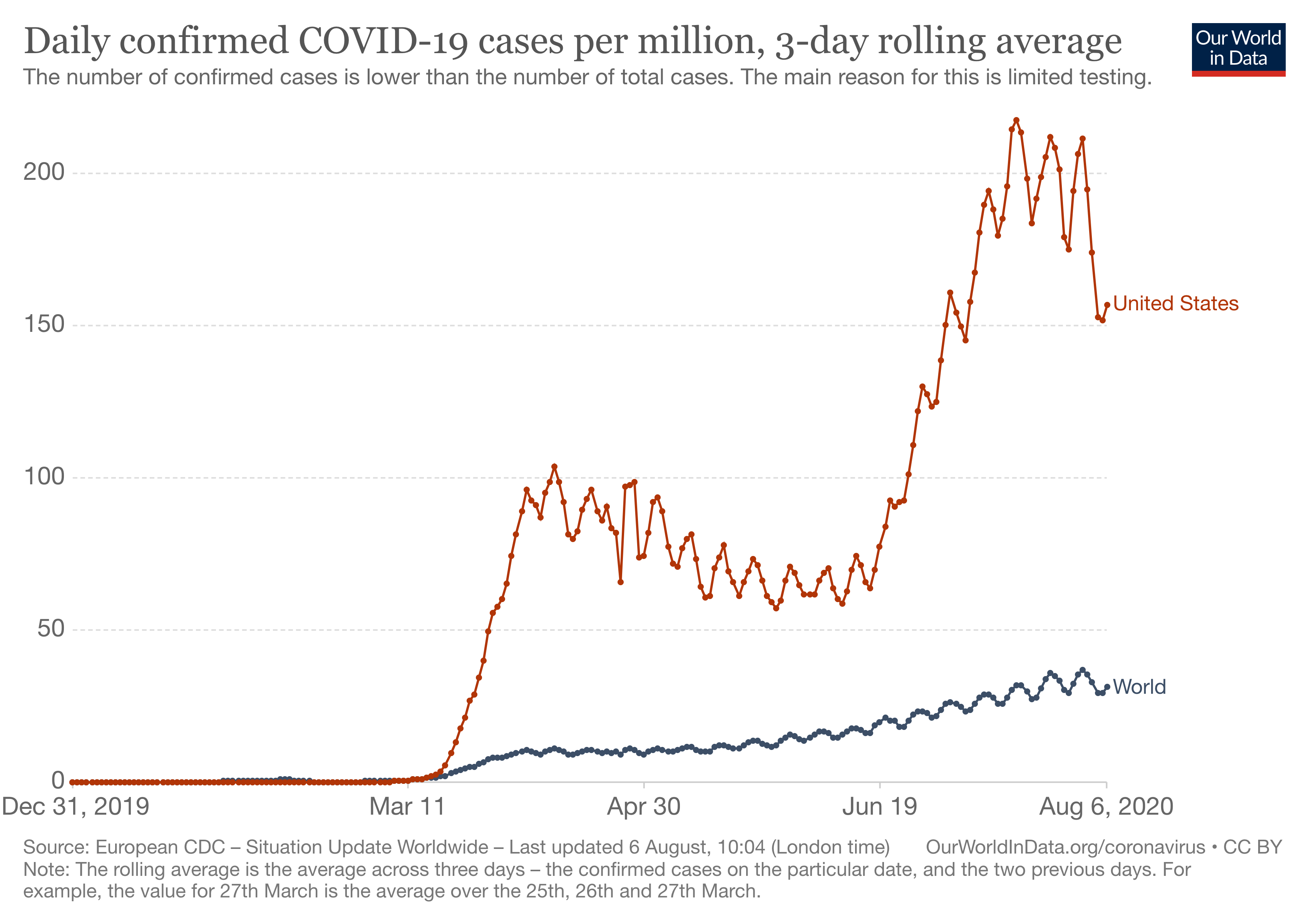

But that’s not the end of the story. All that capitalist growth has been anything but steady. The two most severe economic downturns since the Great Depression of the 1930s have happened in the new millennium: the Second Great Depression (after the crash of 2007-08) and the Pandemic Depression (with the outbreak and spread of the novel coronavirus). In both cases, hundreds of millions of workers around the world were laid off or had their pay cut. Many of them were already struggling to get by, with stagnant wages and precarious jobs, even before economic conditions took a turn for the worse.

And then those same workers had to look up and see one part of the economy recovering—for example, the profits of their employers and shares in the stock market that fueled the wealth of the billionaires—while the one in which they earned their livelihoods barely budged.

Meanwhile, those stunning global cities and urban centers, the likes of which the world has never seen, also include vast slums and informal settlements—parking lots for the working poor. According to the United Nations, over 1 billion people now live in dense neighborhoods with unreliable and often shared access to basic services like water, sanitation and electricity. Many don’t have bank accounts, basic employment contracts, or insurance. Their incomes and workplaces are not on any government agency’s radar.

They’re not so much left behind but, just like their counterparts in the poor neighborhoods of rich countries, incorporated into capitalism on a profoundly unequal basis. They’re forced to compete with one another for substandard housing and low-paying jobs while suffering from much higher rates of crime and environmental pollution than those who live in the wealthy urban neighborhoods. In countries like the United States and the United Kingdom, a disproportionate number are ethnic and racial minorities and recent immigrants.

The working poor in both urban and rural areas are also the ones most affected by the climate crisis. A product of capitalism’s growth, not only in recent decades, but since its inception, global warming has created a world that is crossing temperature barriers which, within a decade, threaten ecosystem collapse, ocean acidification, mass desertification, and coastal areas being flooded into inhabitability.

Meanwhile, the democratic principles and institutions that people have often relied on to make their voices heard are being challenged by political elites and movements that are fueled by and taking advantage of the resentments created by decades of capitalist growth. The irony, of course, is many of these political parties were elected through democratic means and call for more, not less, unbridled capitalism as the way forward.

Clearly, the other side of the coin of capitalism’s tremendous successes have been spectacular failures.

So, it should come as no surprise that there’s more interest these days in both criticisms of and alternatives to capitalism. And Marxian economics is one of the key sources for both: for ways of analyzing capitalism that point to these and other failures not as accidents, but as intrinsic to the way capitalism operates as a system; and for ideas about how to imagine and create other institutions, fundamentally different ways of organizing economic and social life.

Young people, especially, have become interested in the tradition of Marxian economics. They’re trying to pay for their schooling, find decent jobs, and start rewarding careers but they’re increasingly dissatisfied with the effects of the economic system they’re inheriting. Mainstream economics seems to offer less and less to them, especially since it has mostly celebrated and offered policies to strengthen that same economic system. Or, within more liberal parts of mainstream economics, offer only minor changes to keep the system going.

Marxian economics offers a real alternative—in terms of criticizing capitalism and the possibility of creating an economic system that actually delivers longstanding promises of fairness and justice.