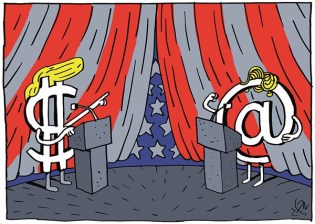

Donald Trump doesn’t know what he’s talking about. But he owned Hillary Clinton during the first part of Monday’s debate. And his attacks on free trade are in fact resonating among working-class voters.

That, and the fact that the polls show the presidential election much closer at this stage than anyone expected, has finally made others sit up and take notice.*

I weighed in back in July, trying to move the debate beyond the free trade-protectionism terms in which it has been framed. Now, we have Peter Goodman, who understands that “Trade is under attack in much of the world, because economists failed to anticipate the accompanying joblessness, and governments failed to help.”**

Goodman makes a number of good observations—about the role “libraries full of economics textbooks” played in promoting free trade and the fact that, even if manufacturing plants returned to the United States, “robots would probably capture most of the jobs.”

But what really interests me about Goodman’s article are the comments from readers. Here is a small sample:

From Mitch Gitman (in Seattle)—

Economists failed to anticipate the job losses stemming from unleashing a Hobbesian race to the bottom on the global economy?! I think they all knew full well, but they weren’t so concerned because it wasn’t their jobs being lost. Just like these economists don’t belong to the generations that are going to be bearing the brunt of the environmental impacts of this sudden race to burn all the fossil-fuel resources that our only planet has taken hundreds of millions of years to accumulate.

Economists are supposed to be the professionals who are smart enough to see the big picture, but economists have to pay the bills too. And there was never going to be a demand for an economist with the simple common sense to see the really big picture, that being able to buy marginally cheaper goods at Walmart is the classic case of knowing the price of everything and the value of nothing.

Bill Maher had a great line from his commentary at the end of last Friday’s episode of his HBO show “Real Time.” To people who ask, “Why doesn’t our economy work for people like me?” His response: “Because it’s not designed to.”

From Kate Flannery (in New York)—

At it’s barren heart, it’s not about trade, it’s about profit at any cost to the public good or just simply human life.

We wouldn’t need lower cost consumer goods, if people had decent income to purchase what they need or want in a sustainable way. Products that are cheap, but fall apart after a year is not the way life should be, nor is it environmentally just.

Every economic lie and political spin about the glories of globalization is just that – a lie to enable corporations and the rich to have even more. American agricultural giants wanted more markets for their horrible products, sending corn into Mexico, a country that didn’t need it. This drove Mexican farmers out of business and destabilized workers who fled north to find work, or crowded into cities to become slave workers for corporations at minimal wages. And that’s just one small example of its immoral and devastating effects.

Globalization and its attendant trade are a main contributor to environmental degradation around the globe as well.

The whole idea of glorious trade and globalization and all the rest, is just a monumental lie serving to enrich the few at the expense of the many. It’s been sold to the public at extraordinary cost. But people are waking up and realizing that those we elect to protect and serve the interests of society have only their self interests and those at the top of the food chain – corporations and finance – are just hollow men and women.

It’s about profit. Nothing else.

And LindaP (in Boston)—

It breaks my heart that the city where I grew up –Fall River, MA, the Spindle City– is a Trump stronghold. It is against the self-interest of those supporters, but as one who lived through the shut down of a city and the hopelessness that ensues, I (kinda) get it.

On hot summer vacation days in the ’60s, we kids would walk through the city. Factory windows would be open. The clack and whir of sewing machines and other manufacturing equipment was as familiar as crickets in the evening. Both my parents — my entire family, actually — worked in those mills.

No one was rich, living in three-deckers and saving up for the American Dream of owning a home, which many went on to do. In those neighborhoods of three-deckers there was cleanliness, pride of place, community, and a real knowledge (not false hope) that you could progress and make a better life for your family. No one was looking to live in a gilded tower — just a nice home, good schools, a living wage, and a better life for ones children.

Then the mills went dark, one by one. Everyone I knew who made their lives in those jobs had to move on. There were still other union jobs to get in the late 60s, so we survived. By the time my parents retired, I saw opportunity dry up for those behind them.

The loss of manufacturing allowed poverty, addiction, and a true hopelessness to take hold. Maybe you have to live it to know how devastatingly true that is.

There’s more wisdom in those comments, about the causes and consequences of free trade, than one will find in Trump’s speeches and the libraries full of mainstream economics textbooks—or, for that matter, in the revised policy positions on Hillary Clinton’s web site.

*Clearly, the Brexit vote has also had an impact.

**To be clear, mainstream economists are the ones who failed to anticipate the negative effects, and both Democratic and Republican governments failed to help workers.