Special mention

Posts Tagged ‘free trade’

Cartoon of the day

Posted: 8 October 2019 in UncategorizedTags: Biden, Canada, cartoon, drugs, free trade, healthcare, labor, Obamacare, Trump, Ukraine

0

Cartoon of the day

Posted: 21 November 2018 in UncategorizedTags: cartoon, exploitation, free trade, freedom, Marx, Marxism, politics, religion

Cartoon of the day

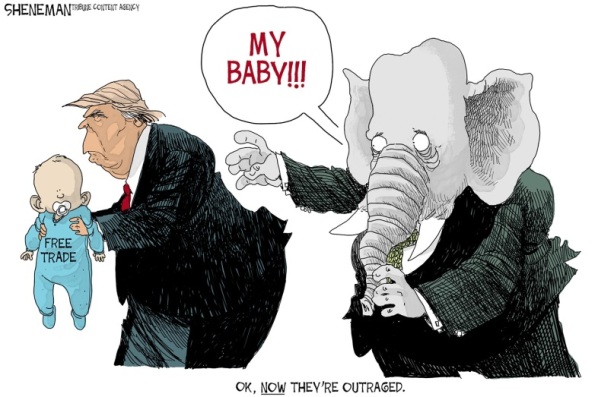

Posted: 8 July 2018 in UncategorizedTags: Cabinet, cartoon, free trade, GOP, Nicaragua, Republicans, revolution, Sandino, tariffs, Trump

Cartoon of the day

Posted: 18 April 2018 in UncategorizedTags: cartoon, children, free trade, guns, justice, markets, students, United States, violence

Utopia and trade

Posted: 28 February 2018 in UncategorizedTags: Adam Smith, capitalism, classes, classical, comparative advantage, Dani Rodrick, David Ricardo, economics, free trade, globalization, Greg Mankiw, international trade, neoclassical, Paul Krugman, Paul Samuelson, protectionism, tariffs, Trump, utopia

Donald Trump’s decision to impose import tariffs—on solar panels and washing machines now, and perhaps on steel and aluminum down the line—has once again opened up the war concerning international trade.

It’s not a trade war per se (although Trump’s free-trade opponents have invoked that specter, that the governments of other countries may retaliate with their import duties against U.S.-made products), but a battle over theories of international trade. And those different theories are related to—as they inform and are informed by—different utopian visions.

In one sense, Trump and his supporters are right. Capitalist free trade has destroyed cities, regions, livelihoods, and industries. The international trade deals the United States has signed in recent decades have been rigged for the wealthy and have cheated workers. They are replete with marketing scams, hustles, and shady deals, to the advantage of large corporations and a small group of individuals at the top.

But Trump, like all right-wing populists, as I explained recently, offers a utopian vision that looks backward, conjuring up and then offering a return to a time that is conceived to be better. For Trump, that time is the 1950s, when a much larger share of U.S. workers was employed in manufacturing and American industry successfully competed against businesses in other countries. The turn to import tariffs is a way of invoking that nostalgia, the selective vision of a utopia that was exceptional, in terms of both U.S. and world history, and that conveniently conceals or overlooks many other aspects of that lost time, such as worker exploitation, Jim Crow racism, and widespread patriarchy inside and outside households.

It should come as no surprise that mainstream economists, today and in a tradition that goes back to Adam Smith and David Ricardo, oppose Trump’s tariffs and hold firmly to the gospel of free international trade. Once again, Gregory Mankiw has stepped forward to articulate the neoclassical view (buttressed by classical antecedents) that everyone benefits from free international trade:

Ricardo used England and Portugal as an example. Even if Portugal was better than England at producing both wine and cloth, if Portugal had a larger advantage in wine production, Portugal should export wine and import cloth. Both nations would end up better off.

The same principle applies to people. Given his athletic prowess, Roger Federer may be able to mow his lawn faster than anyone else. But that does not mean he should mow his own lawn. The advantage he has playing tennis is far greater than he has mowing lawns. So, according to Ricardo (and common sense), Mr. Federer should hire a lawn service and spend more time on the court.

That’s the basis of neoclassical utopianism—the gains from trade: when international trade is unregulated, and every country specializes according to its comparative advantage, more commodities can be produced at a lower cost and as a result average living standards around the world are improved.

Like Mankiw, most mainstream economists, who are the only ones represented in the IGM Economic Experts panel, oppose import tariffs (as seen in the chart above) and celebrate the utopianism of free international trade.

That’s true even among mainstream economists who have argued that, in reality, the causes and consequences of international trade may not coincide with the rosy picture produced within the usual textbook versions of neoclassical economic theory.

For example, Paul Krugman was awarded the Nobel Prize in economics for his work demonstrating that the relative advantages most neoclassical economists take as given are in fact products of history. Thus, it is possible for countries to enhance their trade advantages (through creating internal economies of scale) by regulating international trade. But Krugman was also quick to belittle “a steady drumbeat of warnings about the threat that low-wage imports pose to U.S. living standards” and, then, in his first New York Times column, to denounce the critics of the World Trade Organization.

A few years later Paul Samuelson, widely recognized as the dean of modern mainstream economics, published an article in the Journal of Economic Perspectives in which he challenged the presumed universal benefits of free trade. It is quite possible, Samuelson argued, that if enough higher-paying jobs were lost by American workers to outsourcing, then the gains from the cheaper prices may not compensate for the losses in U.S. purchasing power. In other words, the low wages at the big-box stores do not necessarily make up for their bargain prices. And then Samuelson was immediately taken to task by other mainstream economists, most notably Jagdish Bhagwati (along with his coauthors, Arvind Panagariya and T.N. Srinivasan [pdf]), who argued that “that outsourcing is fundamentally just a trade phenomenon [and] leads to gains from trade.”

Finally, Dani Rodrick, the mainstream economist who has been most critical of the role his colleagues have played as “cheerleaders” for capitalist globalization, still defends the standard models of international trade:

It has long been an unspoken rule of public engagement for economists that they should champion trade and not dwell too much on the fine print. This has produced a curious situation. The standard models of trade with which economists work typically yield sharp distributional effects: income losses by certain groups of producers or worker categories are the flip side of the “gains from trade.” And economists have long known that market failures – including poorly functioning labor markets, credit market imperfections, knowledge or environmental externalities, and monopolies – can interfere with reaping those gains.

But Rodrick, like Krugman, Samuelson, and other mainstream economists who have identified problems with the story told by Mankiw, Bhagwati, and other free-traders—who have “consistently minimized distributional concerns” and “overstated the magnitude of aggregate gains from trade deals”—still holds to the neoclassical utopianism that, with “all of the necessary distinctions and caveats,” more international trade can and should be promoted. Thus, as Rodrick argued just last week,

If our economic rules empower corporations and financial interests excessively, then the correct response is to rewrite those rules — at home as well as abroad. If trade agreements serve mainly to reshuffle income to capital and corporations, the answer is to rebalance them to make them friendlier to labor and society at large.

The goal is to make sure everyone, not just “corporations and financial interests,” benefits from international trade.

But recent criticisms of trade deals from within mainstream economics still don’t include the possibility that capitalism itself, with or without free international trade and multinational trade agreements, however the rules are written, privileges one class over another. Capital gains at the expense of workers because it is able to extract a surplus for literally doing nothing. That kind of social theft occurs—both when international trade is regulated and controlled and when it is allowed to operate free of any such interventions.

That’s why Karl Marx ironically came out in support of free trade in his famous speech to the Democratic Association of Brussels at its public meeting of 9 January 1848:

If the free-traders cannot understand how one nation can grow rich at the expense of another, we need not wonder, since these same gentlemen also refuse to understand how within one country one class can enrich itself at the expense of another.

Do not imagine, gentlemen, that in criticizing freedom of trade we have the least intention of defending the system of protection.

One may declare oneself an enemy of the constitutional regime without declaring oneself a friend of the ancient regime.

Moreover, the protectionist system is nothing but a means of establishing large-scale industry in any given country, that is to say, of making it dependent upon the world market, and from the moment that dependence upon the world market is established, there is already more or less dependence upon free trade. Besides this, the protective system helps to develop free trade competition within a country. Hence we see that in countries where the bourgeoisie is beginning to make itself felt as a class, in Germany for example, it makes great efforts to obtain protective duties. They serve the bourgeoisie as weapons against feudalism and absolute government, as a means for the concentration of its own powers and for the realization of free trade within the same country.

But, in general, the protective system of our day is conservative, while the free trade system is destructive. It breaks up old nationalities and pushes the antagonism of the proletariat and the bourgeoisie to the extreme point. In a word, the free trade system hastens the social revolution. It is in this revolutionary sense alone, gentlemen, that I vote in favor of free trade.

That’s because Marx’s critique of political economy embodied a utopian horizon radically different from the utopianism of classical and neoclassical economics. He sought to transform economic and social institutions in order to eliminate capitalist exploitation. And if free trade was the quickest way of getting to the point when workers revolted and changed the system, then he would vote against protectionism and in favor of free trade.

As it turns out, as Friedrich Engels explained forty years later, both protectionism and free trade serve, in different ways, to produce more capitalist producers and thus to produce more wage-laborers. In our own time, Trump’s protective tariffs may do that in the United States, just as free trade has accomplished that in other countries that have increased their exports to the United States.

But neither protectionism nor free trade can succeed in undoing the “elephant curve” of global inequality, which in recent decades has shifted the fortunes of workers in the United States and Western Europe and those in “emerging” countries and still left all of them falling further and further behind the top 1 percent in their own countries and globally.

Reversing that trend is a goal, a utopian horizon, worth fighting for.

Globalization—how did they get it so wrong?

Posted: 21 July 2017 in UncategorizedTags: capitalism, colonialism, Dani Rodrik, economics, free markets, free trade, globalization, heterodox, imperialism, inequality, mainstream, Marx, Paul Krugman

There is perhaps no more cherished an idea within mainstream economics than that everyone benefits from free trade and, more generally, globalization. They represent the solution to the problem of scarcity for the world as a whole, much as free markets are celebrated as the best way of allocating scarce resources within nations. And any exceptions to free markets, whether national or international, need to be criticized and opposed at every turn.

That celebration of capitalist globalization, as Nikil Saval explains, has been the common sense that mainstream economists, both liberal and conservative, have adhered to and disseminated, in their research, teaching, and policy advice, for many decades.

Today, of course, that common sense has been challenged—during the Second Great Depression, in the Brexit vote, during the course of the electoral campaigns of Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump—and economic elites, establishment politicians, and mainstream economists have been quick to issue dire warnings about the perils of disrupting the forces of globalization.

I have my own criticisms of Saval’s discussion of the rise and fall of the idea of globalization, especially his complete overlooking of the long tradition of globalization critics, especially on the Left, who have emphasized the dirty, violent, unequalizing underside of colonialism, neocolonialism, and imperialism.*

However, as a survey of the role of globalization within mainstream economics, Saval’s essay is well worth a careful read.

In particular, Saval points out that, in the heyday of the globalization consensus, Dani Rodrick was one of the few mainstream economists who had the temerity to question its merits in public.

And who was one of the leading defenders of the idea that globalization had to be celebrated and it critics treated with derision? None other than Paul Krugman.

Paul Krugman, who would win the Nobel prize in 2008 for his earlier work in trade theory and economic geography, privately warned Rodrik that his work would give “ammunition to the barbarians”.

It was a tacit acknowledgment that pro-globalisation economists, journalists and politicians had come under growing pressure from a new movement on the left, who were raising concerns very similar to Rodrik’s. Over the course of the 1990s, an unwieldy international coalition had begun to contest the notion that globalisation was good. Called “anti-globalisation” by the media, and the “alter-globalisation” or “global justice” movement by its participants, it tried to draw attention to the devastating effect that free trade policies were having, especially in the developing world, where globalisation was supposed to be having its most beneficial effect. This was a time when figures such as the New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman had given the topic a glitzy prominence by documenting his time among what he gratingly called “globalutionaries”: chatting amiably with the CEO of Monsanto one day, gawking at lingerie manufacturers in Sri Lanka the next. Activists were intent on showing a much darker picture, revealing how the record of globalisation consisted mostly of farmers pushed off their land and the rampant proliferation of sweatshops. They also implicated the highest world bodies in their critique: the G7, World Bank and IMF. In 1999, the movement reached a high point when a unique coalition of trade unions and environmentalists managed to shut down the meeting of the World Trade Organization in Seattle.

In a state of panic, economists responded with a flood of columns and books that defended the necessity of a more open global market economy, in tones ranging from grandiose to sarcastic. In January 2000, Krugman used his first piece as a New York Times columnist to denounce the “trashing” of the WTO, calling it “a sad irony that the cause that has finally awakened the long-dormant American left is that of – yes! – denying opportunity to third-world workers”.

The irony is that Krugman won the Nobel Prize in Economics in recognition of his research and publications that called into question the neoclassical idea that countries engaged in and benefited from international trade based on given—exogenous—resource endowments and technologies. Instead, Krugman argued, those endowments and technologies were created historically and could be changed by government policies, including histories and policies that run counter to free trade and globalization.

Krugman was thus the one who gave theoretical “ammunition to the barbarians.” But that was the key: he considered the critics of globalization—the alter-globalization activists, heterodox economists, and many others—”barbarians.” For Krugman, they were and should remain outside the gates because, in his view, they were not trained in or respectful of the protocols of mainstream economics. The “barbarians” could not be trusted to understand or adhere to the ways mainstream economists like Krugman analyzed the exceptions to the common sense of globalization. They might get out of control and develop other arguments and economic institutions.

But then the winds began to shift.

In the wake of the financial crisis, the cracks began to show in the consensus on globalisation, to the point that, today, there may no longer be a consensus. Economists who were once ardent proponents of globalisation have become some of its most prominent critics. Erstwhile supporters now concede, at least in part, that it has produced inequality, unemployment and downward pressure on wages. Nuances and criticisms that economists only used to raise in private seminars are finally coming out in the open.

A few months before the financial crisis hit, Krugman was already confessing to a “guilty conscience”. In the 1990s, he had been very influential in arguing that global trade with poor countries had only a small effect on workers’ wages in rich countries. By 2008, he was having doubts: the data seemed to suggest that the effect was much larger than he had suspected.

And yet, as Saval points out, mainstream economists’ recognition of the unequalizing effects of capitalist globalization has come too late: “much of the damage done by globalisation—economic and political—is irreversible.”

The damage is, of course, only irreversible within the existing economic institutions. Imagining and enacting a radically different way of organizing the economy would undo that damage and benefit those who have been forced to have the freedom to submit to the forces of capitalist globalization.

But Rodrik and Krugman—and mainstream economists generally—don’t seem to be interested in participating in that project, which would give the “barbarians” a say in creating a different kind of globalization, beyond capitalism.

*Back in 2000—and in a series of articles, book chapters, and blog posts since then—I have attempted to rethink the relationship between capitalist globalization and imperialism. Marxist economist Prabhat Patnaik has also made the case for the continuing relevance of imperialism as an analytical construct for understanding and challenging effectively the logic and dynamics of contemporary capitalism.

Beyond Trump and free trade

Posted: 26 January 2017 in UncategorizedTags: economics, elites, free trade, inequality, international trade, mainstream, Mexico, NAFTA, TPP, Trump, United States, working-class

Now that President Trump has begun carrying out his campaign pledges to undo America’s trade ties, formally withdrawing the United States from the Trans-Pacific Partnership and announcing he will start to renegotiate the North American Free Trade Agreement, it’s time to analyze what this means.

As it turns out, I’d already started to do this before the election, with a series of posts (e.g., here, here, here, and here) on Trump and the mounting criticism of the trade agreements the United States had signed (such as NAFTA) or was in the process of negotiating (the TPP).

It’s clear Trump’s decisions—which he claims are a “Great thing for the American worker”—challenge the view of economic and political elites, as well as those of mainstream economists (such as Brad DeLong), in the United States and around the world that everyone benefits from free trade.*

But, we now know, there has also been a growing counter-narrative, that not everyone has gained from growing international trade and trade agreements, which have generated unequal benefits and costs. What’s interesting about this alternative story, at least when it comes to NAFTA, is that critics on each side argue the other side is the one that has benefited: U.S. critics that Mexico has gained, and just the opposite in Mexico, that the United States has captured the lion’s share of the benefits from NAFTA.

Here’s the problem: workers on both sides of the border have lost out, and their losses are mostly not due to NAFTA.

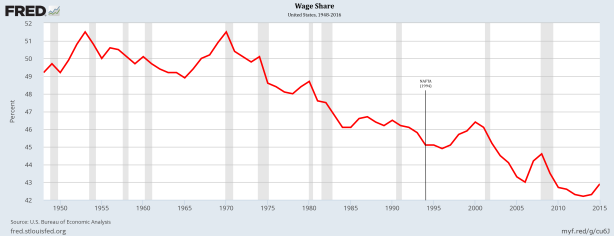

We know, for example, that the wage share of national income in the United States has in fact declined after NAFTA was implemented (in January 1994)—from 45.1 percent of gross domestic income to 42.9 percent. But we also have to recognize workers have been losing out since at least 1970, when the wage share stood at 51.5 percent.

Much the same has been happening in Mexico, where (according to the research of Norma Samaniego Breach [pdf]), the wage share (the dark green line in the chart above) has been falling since 1978—and continued to fall after NAFTA was put into place. And, as Alice Krozera, Juan Carlos Moreno Brid, and Juan Cristóbal Rubio Badan have shown, economic and political elites in Mexico, much like their U.S. counterparts, have mostly ignored the problem of inequality and resisted efforts to raise the minimum wage and workers’ share of national income.

The fact is, while NAFTA did propel a large increase in trade between Mexico and the United States, it “did not cause the huge job losses feared by the critics or the large economic gains predicted by supporters” (according to a 2015 study commissioned by the Congressional Research Service [pdf]).

The bottom line is, eliminating or renegotiating NAFTA—including in the manner Trump is proposing—is not going to help the working-classes in either Mexico or the United States. It is merely a diversion from the real changes that need to be made, to which the political and economic elites as well as mainstream economists in both countries stand opposed.

*The only real debate within mainstream economics is between neoclassical economists who argue free trade generates the most efficient outcomes, within and between countries (regardless of whether countries run trade surpluses or deficits), and their critics (such as Jared Bernstein) who argue that trade deficits lead to a loss of jobs (e.g., in U.S. manufacturing), and thus require interventions of the sort Trump is proposing to change the pattern of international trade.

China syndrome

Posted: 16 December 2016 in UncategorizedTags: accumulation, capital, China, corporations, economics, elites, free trade, international trade, mainstream, politics, United States, workers

There are two sides to the recent China Shock literature created by David Autor and David Dorn and surveyed by Noah Smith.

On one hand, Autor and Dorn (with a variety of coauthors) have challenged the free-trade nostrums of mainstream economists and economic elites—that everyone benefits from free international trade. Using China as an example, they show that increased trade hurt American workers, increased political polarization, and decreased U.S. corporate innovation.

The case for free international trade now lies in tatters, which of course played an important role in the Brexit vote as well as in the U.S. presidential campaign.

On the other hand, invoking the China Shock has tended to reinforce economic nationalism—treating China as an unitary entity, a country has shaken up world trade patterns, and disregarding the conditions and consequences of increased trade with other countries, including the United States.

Why has there been an increasing U.S. trade deficit with China in recent decades? As James Chan explained, in response to an August 2016 article in the Wall Street Journal,

Our so-called China problem isn’t really with the Chinese but rather our own multinational companies.

As I see it, U.S. corporations have made a variety of decisions—to subcontract the production of parts and components with enterprises in China (which are then used in products that are later imported into the United States), to purchase goods produced in China to sell in the United States (which then show up in U.S. stores), to outsource their own production of goods (to sell in China and to export to the United States), and so on. The consequences of those corporate decisions (and not just with respect to China) include disrupting jobs and communities in the United States (through outsourcing and import competition) and decreasing innovation (since existing technologies can be used both to produce goods in China and sell in the expanding Chinese consumer market), thereby increasing political polarization in the United States.

The flip side of the story is the accumulation of capital in China. Until the development of the conditions for the development of capitalism existed in China, none of those corporate decisions were possible—not by U.S. corporations nor by multinational enterprises from other countries, all of whom were eager to take advantage of the growth of capitalism in China. Which of course they then contributed to, thus spurring the widening and deepening of capital accumulation within China.

It should come as no surprise, then, that there’s been an upsurge of strike activity by workers in the fast-growing centers of manufacturing and construction within China—especially in the provinces of Guandong, Shandong, Henan, Sichuan, and Hebei.

According to Hudson Lockett, China this year

saw a total of 1,456 strikes and protests as of end-June, up 19 per cent from the first half of 2015

The problem with the China Shock literature, which has served to challenge the celebration of free-trade by mainstream economists and economic elites in the West, is that it hides from view both the decisions by U.S. corporations that have increased the U.S. trade deficit with China (with the attendant negative consequences “at home”) and the activity by Chinese workers to contest the conditions under which they have been forced to have the freedom to labor (which we can expect to continue for years to come).

It’s our responsibility to keep those decisions and events in view. Otherwise, we risk the economic and political equivalent of the China Syndrome.

Uncertainty and the election

Posted: 18 November 2016 in UncategorizedTags: Brexit, certainty, Colombia, economics, election, free trade, globalization, mainstream, models, peace, polls, pollsters, statistics, uncertainty, United States

Mark Tansey, “Coastline Measure” (1987)

The pollsters got it wrong again, just as they did with the Brexit vote and the Colombia peace vote. In each case, they incorrectly predicted one side would win—Hillary Clinton, Remain, and yes—and many of us were taken in by the apparent certainty of the results.

I certainly was. In each case, I told family members, friends, and acquaintances it was quite possible the polls were wrong. But still, as the day approached, I found myself believing the “experts.”

It still seems, when it comes to polling, we have a great deal of difficulty with uncertainty:

Berwood Yost of Franklin & Marshall College said he wants to see polling get more comfortable with uncertainty. “The incentives now favor offering a single number that looks similar to other polls instead of really trying to report on the many possible campaign elements that could affect the outcome,” Yost said. “Certainty is rewarded, it seems.”

But election results are not the only area where uncertainty remains a problematic issue. Dani Rodrik thinks mainstream economists would do a better job defending the status quo if they acknowledged their uncertainty about the effects of globalization.

This reluctance to be honest about trade has cost economists their credibility with the public. Worse still, it has fed their opponents’ narrative. Economists’ failure to provide the full picture on trade, with all of the necessary distinctions and caveats, has made it easier to tar trade, often wrongly, with all sorts of ill effects. . .

In short, had economists gone public with the caveats, uncertainties, and skepticism of the seminar room, they might have become better defenders of the world economy.

To be fair, both groups—pollsters and mainstream economists—acknowledge the existence of uncertainty. Pollsters (and especially poll-based modelers, like one of the best, Nate Silver, as I’ve discussed here and here) always say they’re recognizing and capturing uncertainty, for example, in the “error term.”

Even Silver, whose model included a much higher probability of a Donald Trump victory than most others, expressed both defensiveness about and confidence in his forecast:

Despite what you might think, we haven’t been trying to scare anyone with these updates. The goal of a probabilistic model is not to provide deterministic predictions (“Clinton will win Wisconsin”) but instead to provide an assessment of probabilities and risks. In 2012, the risks to to Obama were lower than was commonly acknowledged, because of the low number of undecided voters and his unusually robust polling in swing states. In 2016, just the opposite is true: There are lots of undecideds, and Clinton’s polling leads are somewhat thin in swing states. Nonetheless, Clinton is probably going to win, and she could win by a big margin.

As for the mainstream economists, while they may acknowledge exceptions to the rule that “everyone benefits” from free markets and international trade in some of their models and seminar discussions, they acknowledge no uncertainty whatsoever when it comes to celebrating the current economic system in their textbooks and public pronouncements.

So, what’s the alternative? They (and we) need to find better ways of discussing and possibly “modeling” uncertainty. Since the margins of error, different probabilities, and exceptions to the rule are ways of hedging their bets anyway, why not just discuss the range of possible outcomes and all of what is included and excluded, said and unsaid, measurable and unmeasurable, and so forth?

The election pollsters and statisticians may claim the public demands a single projection, prediction, or forecast. By the same token, the mainstream economists are no doubt afraid of letting the barbarian critics through the gates. In both cases, the effect is to narrow the range of relevant factors and the likelihood of outcomes.

One alternative is to open up the models and develop a more robust language to talk about fundamental uncertainty. “We simply don’t know what’s going to happen.” In both cases, that would mean presenting the full range of possible outcomes (including the possibility that there can be still other possibilities, which haven’t been considered) and discussing the biases built into the models themselves (based on the assumptions that have been used to construct them). Instead of the pseudo-rigor associated with deterministic predictions, we’d have a real rigor predicated on uncertainty, including the uncertainty of the modelers themselves.

Admitting that they (and therefore we) simply don’t know would be a start.