In the world according to Paul Krugman, “most Americans” have gotten considerably richer over the past two years (even if “the gains have been especially big at the top”), “lower-income Americans [have] seen relatively large income gains,” and “the simple story that the pandemic has been great for the wealthy and bad for the working class doesn’t hold up.”

Really?

To support his argument, Krugman trots out a series of charts from Realtime Inequality, which is in fact an eye-opening set of statistics on wealth and income inequality in the United States. But not in the way Krugman uses them. The two biggest problems in Krugman’s treatment are (a) he excludes the bottom 50 percent (so that “most Americans” refers only to the middle 40 percent) and (b) he focuses on growth rates and not levels or shares of income and wealth (so that, once again, we have that pesky problem of large percentage increases on a low base yields small increases).

That’s how you lie with inequality statistics.

What happens if you look at other statistics? Let’s start with wealth.

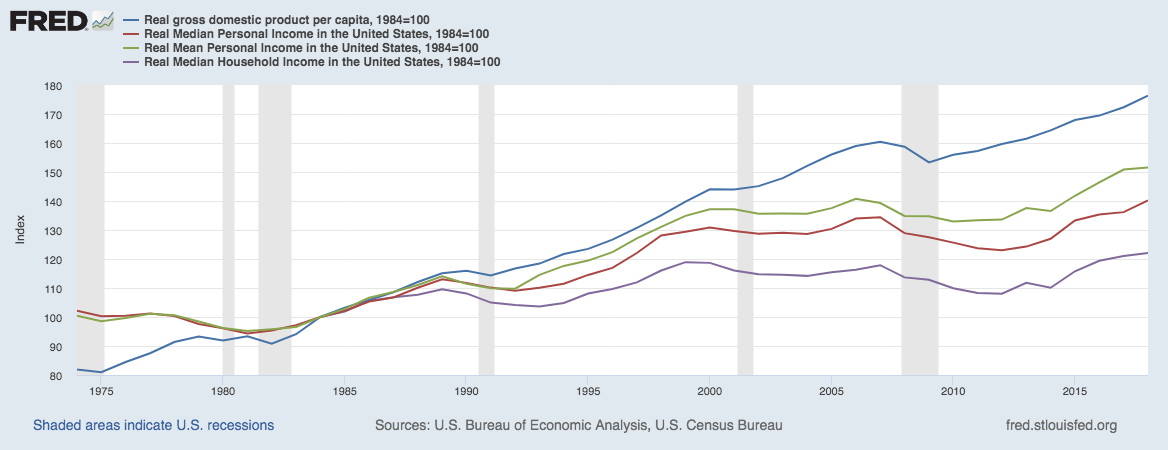

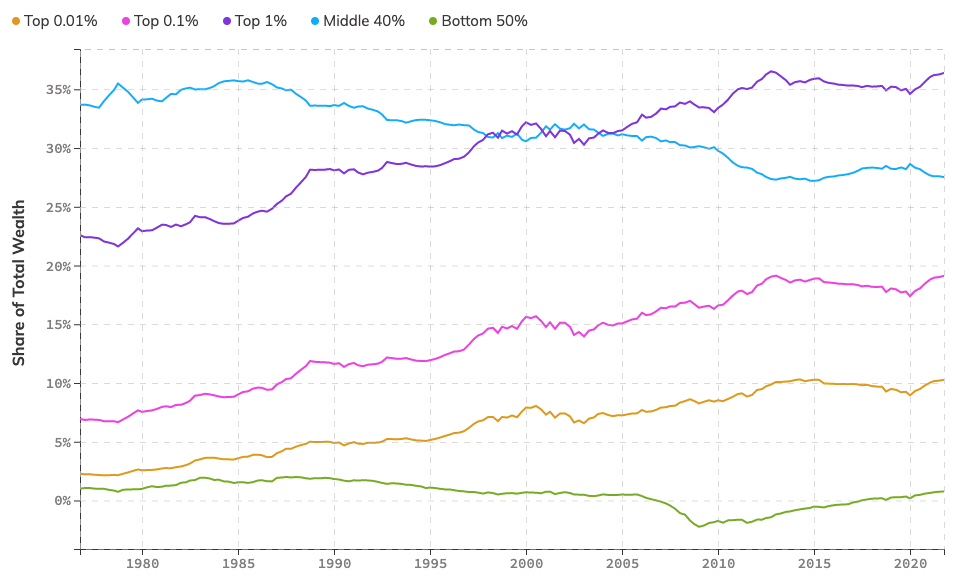

Here, I’ve depicted the shares of wealth for various deciles of the U.S. population: top 0.01 percent, top 0.1 percent, top 1 percent, middle 40 percent, and bottom 50 percent. Lo and behold, we can see that, starting in 1979, the shares of wealth held by those at the very top have soared, the share of the middle 40 percent has fallen, and the share of the bottom 50 percent hasn’t budged.

What about for the most recent period (which is what Krugman focuses on), from the end of 2019 to the end of 2021. Same thing: the shares of wealth of the top 1 percent (and subsets of that group) have continued to rise, the share of the middle 40 percent has fallen, and the share of the bottom 50 percent has actually risen.

Wow! The share of wealth owned by the bottom 50 percent (which consists mostly of housing they may own) has gone up. By how much? From a minuscule amount to another minuscule amount—from 0.3 percent to 0.8 percent. Or, in absolute terms, from an average wealth of $2.9 thousand to $7.9 thousand—a difference of $5 thousand. You might even say such an increase means a lot to the 125 million people in the bottom 50 percent of the U.S. population but it’s certainly no more than a drop in the bucket in terms of closing the gap with the wealth of those at the top (for example, the $19 million of wealth owned by those in the top 1 percent).

What about income? Same problem.

The growth rate of post-tax income for those in the bottom 50 percent was, in fact, much higher than for those in the middle 40 percent and top 1 percent—8.5 percent compared to 3.8 percent and 4.1 percent, respectively.

And that proves what? Not much. Those in the bottom 50 percent gained $2.8 thousand (mostly from transfer payments), which is similar to the gain for those in the middle 40 percent ($3.2 thousand). And those in the top 1 percent? Well, they managed to capture an extra $48 thousand during the period from late 2019 to late 2021.

So, sure, wages for those at the bottom are growing at a faster rate than those at the top. But they’re still barely staying ahead of inflation. And they’re not such as to even put a dent in the gap that separates them from the incomes captured by those at the top. The share of post-tax income taken home by all those workers in the bottom 50 percent only increased from 20.1 percent to 20.9 percent, while the share of income captured by the 2.5 million people in the top 1 percent is still 14.4 percent.

All of which means what? That the gap between workers at the bottom (including those in the middle) and the small group at the top continues to be enormous—in terms of both wealth and income. And no policy of keeping existing interest-rates or increasing them will help close that obscene gap.

It’s time we stop lying with inequality statistics and focus on the real culprit: all the ways contemporary capitalism, both before and during the pandemic, has managed to funnel most of the surplus to those at the top of the economic pyramid, leaving barely enough wealth and income to get by for everyone else.

It’s a “simple story,” with clear political implications. Maybe that’s the reason the Krugmans of the world don’t want to tell it. . .