The official unemployment rate has fallen to 5.1 percent. So, according to mainstream economists, the U.S. economy is now at full employment.* And, in order to prevent inflation, it’s time for the Fed to raise interest-rates.

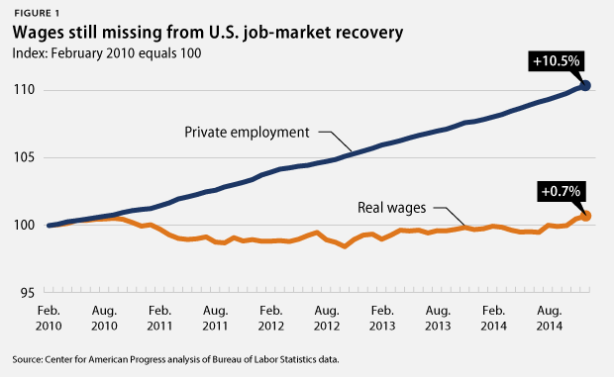

The problem, of course, is we should expect to see wages going up at such low levels of unemployment—and we’re not. Not by a long shot. So, what’s going on?

As I see it, what mainstream economists are missing is the fact that the headline rate doesn’t take into account the millions of workers (a) who have been out of work for a very long time (many of whom want a job but are too discouraged to be actively looking for a job) or (b) who are forced to take one or more part-time jobs (when they really want a full-time job) or (c) who have taken a low-wage job (but the bulk of new jobs that have been created in recent years are in low-wage industries).

That relative surplus population is what is keeping the wages of all workers in line—and allowing corporate profits and incomes at the very top to continue to grow.

Let’s look at each group in turn. First, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the percentage of unemployed workers who have been out of work for 27 weeks and more still stands at 27.7 percent. In fact, that rate of long-term unemployment has been at or above 25 percent for 77 straight months (since April 2009).**

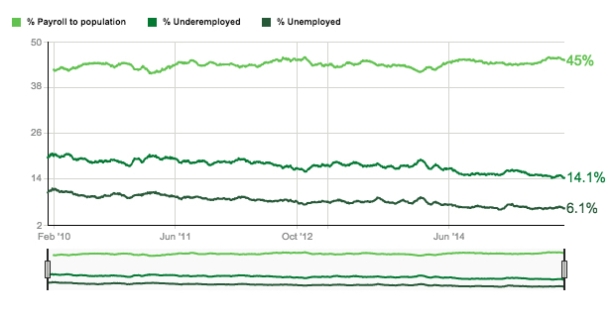

Many of those workers who have been unemployed for a very long time have simply given up actively looking for a job—even though they’d take job if they could find one. They’re joined by millions of other workers who have managed to find part-time jobs but would prefer to be working full-time. That’s called “involuntary part-time work.” While some mainstream economists consider the distinction between voluntary and involuntary part-time work to be “old-fashioned,” the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco notes that

the rate of involuntary part-time work is substantially more elevated, about 30–40% above its level in earlier recoveries. In particular, when the unemployment rate was at its current level of 5.5% in the last two recoveries—mid-1996 and late 2004—the rate of involuntary part-time work was about 3.2%, well below the May 2015 reading of 4.2%.

More generally, the ratio of the rate of involuntary part-time work to the unemployment rate has been rising over time, especially since 2010 but also during the 2002–07 recovery. The ratio rose from about 0.55–0.60 during the late 1990s to about 0.75 in early 2015. This trend increase in the prevalence of involuntary part-time work relative to the unemployment rate suggests that long-term structural factors may be boosting employers’ reliance on part-time work.

Gallup finds the current rate of underemployment to be 14.1 percent.***

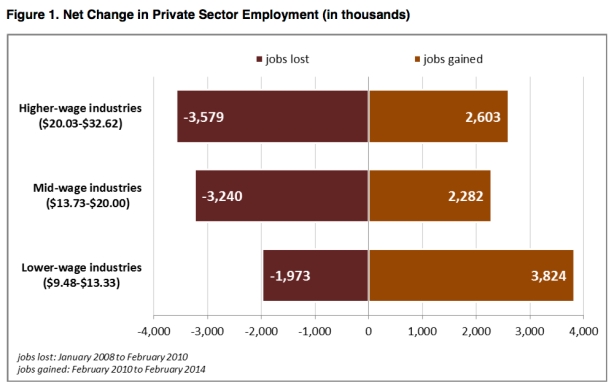

The third group in the Reserve Army are those workers who have managed to find some kind of job during the recent recovery but whose wages are low. According to a 2014 report from the National Employment Law Project (pdf), lower-wage industries accounted for 22 percent of job losses during the recession but 44 percent of employment growth over the previous four years. Thus, as of February 2014, lower-wage industries (from administrative and support and food services to retail and apparel) employed 1.85 million more workers than at the start of the recession. And we know, from a subsequent report, that the real wages in many of those industries declined by 5 percent or more during the recovery (between 2009 and 2014.)

While mainstream economists congratulate themselves on a successful economic recovery, which has lowered the headline unemployment rate and requires now a return to “normal” monetary policy, they accept a situation in which a large Reserve Army of Unemployed, Underemployed, and Low-Wage Workers has both been created by and, in turn, fueled a recovery characterized by stagnant wages for most and growing profits and high incomes for a tiny minority at the very top.

In other words, all mainstream economists are doing is congratulating themselves for a job well done—in supporting an economic system that exists not to serve the needs of workers, but in which workers exist only to serve the needs of their employers.

*Or, in more technical terms, a level of unemployment consistent with non-accelerating inflation.

**In fact, during that entire period, the rate has only dipped below 27 percent for two months (June and July 2015), before rising again.

***Gallup’s notion of underemployment is a bit different from that of the Bureau of Labor Statistics (which reports a level of U6 unemployment of 11.3 percent). It includes (a) workers who are employed part time but want to work full time and (b) workers within the underemployed group who are not employed, even for one hour a week, but are available and looking for work.

[…] is the Industrial Reserve Army, which is missing from the models used by the so-called experts. As I wrote back in […]

[…] even if and when new jobs are created, the effect on workers’ wages will depend on the Reserve Army of Unemployed, Underemployed, and Low-Wage […]

[…] are the statistics that might help us make sense of what is going on out there—numbers like the Reserve Army of Unemployed, Underemployed, and Low-wage Workers or the rate of […]

[…] are the statistics that might help us make sense of what is going on out there—numbers like the Reserve Army of Unemployed, Underemployed, and Low-wage Workers or the rate of […]

[…] the unemployed,” “reserve army of the unemployed and underemployed,” and “reserve army unemployed, underemployed, and low-wage workers” to get at much the same issue. And, as is clear from the chart at the top of the post, the […]

[…] army of the unemployed,” “reserve army of the unemployed and underemployed,” and “reserve army unemployed, underemployed, and low-wage workers” to get at much the same issue. And, as is clear from the chart at the top of the post, the […]

[…] army of the unemployed,” “reserve army of the unemployed and underemployed,” and “reserve army unemployed, underemployed, and low-wage workers” to get at much the same issue. And, as is clear from the chart at the top of the post, the […]