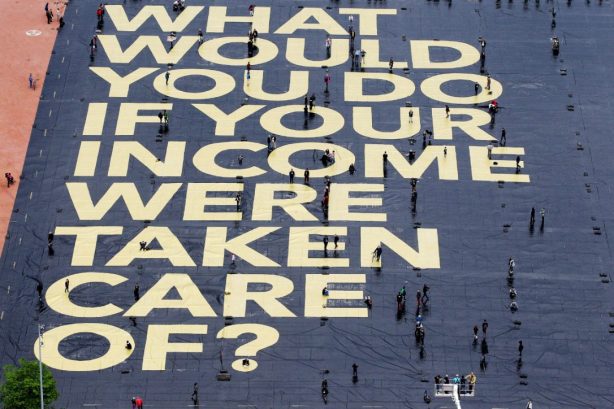

Back in April, I argued the idea of a guaranteed basic income—of “just giving people money”—was attracting more and more attention and support.

And it’s about time, as inequality (already obscene) continues to grow, workers (already embattled) have less and less security on the job (whether because of outsourcing, automation, or just plain corporate reorganization and cost-cutting), and the ranks of the working poor (already enormous) have swelled.

Not surprisingly, it also means it’s being attacked by mainstream economists and economic pundits—like Eduardo Porter.

Porter correctly understands that “A universal income divorces assistance from need.” And that’s exactly what he doesn’t like about it. His preference is to use government assistance to get poor people to do what economic and social engineers want (like moving to better neighborhoods). The extraordinary arrogance and elitism in tying assistance to need in that way haunts everyone who prefers to stick with existing anti-poverty programs. They would be challenged and bypassed by the existence of a guaranteed basic income for everyone, including those who currently fall below the poverty line.

But that’s not Porter’s main argument. It’s rather that “just giving people money” would disrupt the incentive to work.

In this world, though, where work remains an important social, psychological and economic anchor, there are better tools to help than giving every American a monthly check.

That’s the exact same argument regularly invoked by mainstream economists, including most recently by Brad DeLong: that “useful employment” gives people an “honorable and dignified role in society.”

What Porter, DeLong, and most mainstream economists and commentators choose to overlook or ignore is that, in a world in which the majority of people are forced to have the freedom to sell their ability to work to someone else—in which, in short, labor power is a commodity—there’s no necessary honor or dignity in work. It’s a necessity, born of the fact that people need to earn an income to purchase commodities to sustain themselves and to pay off their debts. And the most likely way to earn that income is to sell their ability to work to a small number of other people, their employers, who in turn get to appropriate and do what they will with the profits.

It’s precisely that relationship—along with discourses that tie dignity to work, the continued existence of less-than-successful anti-poverty programs, and much else—that serves to reproduce and reinforce the separation between employees and their employers and to force the former to rely on the latter for their income.

A guaranteed basic income wouldn’t do away with that relationship or the need for most people to work for someone else. But it would certainly give those who work for a living other options—including the ability to find dignity away from and outside of work.

[…] an argument I’ve dealt with before (e.g., here and here). As I see it, there’s nothing necessarily dignified about most people being forced […]

[…] an argument I’ve dealt with before (e.g., here and here). As I see it, there’s nothing necessarily dignified about most people being forced to […]

[…] program or a universal basic income. “Just giving people money” (according to Eduardo Porter) disrupts the incentive to work and undermines the “social, psychological, and economic […]

[…] anti-poverty program or a universal basic income. “Just giving people money” (according to Eduardo Porter) disrupts the incentive to work and undermines the “social, psychological, and economic anchor” […]

[…] for the so-called dignity of work, I can only repeat what I wrote just a couple of years ago: what advocates of getting people back to […]

[…] for the so-called dignity of work, I can only repeat what I wrote just a couple of years ago: what advocates of getting people back to […]