In retrospect, I can now recognize that we were both right and wrong, as is always the case when one tries to look into the future.

— Henning Mankell

Regular readers of this blog know two things about me: I don’t make predictions. And I use these posts not to pronounce firm conclusions or solutions, but to try to work through the issues and clarify my thinking.

So, think of this as an exercise in trying to make sense of the ongoing debate concerning the shape of the recession and the speed of the recovery from the severe economic crisis induced by the response—by U.S. corporations, banks, workers, various levels of the government, and others—to the novel coronavirus pandemic. Nothing more.

Moreover, I don’t have or offer a single theory of capitalists crises, no set of “laws of motion” that inexorably (in either the first or last instance) work themselves out to produce every recession, depression, or other economic meltdown within capitalism. For me, every crisis is a singular event, which requires a conjunctural analysis—and this one is no different.

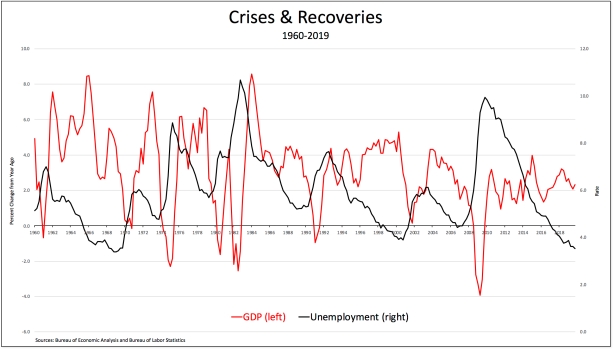

That said, I think we can all agree that the current crisis is severe—in terms of a variety of indicators, from the projected decline in Gross Domestic Product to the current and projected additional rise in unemployment. It’s probably the most dramatic since the first Great Depression of the 1930s, and therefore worse than any of the eight other economic downturns (including what I have called the Second Great Depression) since 1960.*

The big question is, how long will it last—that is, will American capitalism rebound and how quickly will that occur?

That’s the question that seems to be on everyone’s minds these days, from Donald Trump and the right-wing anti-shutdown protestors through businesses and banks both large and small to the millions of workers whose lives have been decimated either by being laid off or being forced to have the freedom to continue to work under conditions that imperil their health and lives.

And the stakes couldn’t be higher. In Trump’s case, for example, a quick recovery increases his chances of reelection in November—although that might not work out exactly as he hopes if reopening the economy prematurely means thousands more American deaths. A longer downturn, on the other hand, calls into question capitalism’s resilience, highlights even more the grotesque levels of inequality that characterize the United States, and serves to legitimize more generous government-sponsored social programs (including, e.g., a universal or unconditional basic income) to mitigate the effects of the crisis on workers, their families, and their communities.

So, what will the COVID-19 recession look like: will it be V-shaped, U-shaped, or W-shaped (to use the alphabet soup most recently discussed by David Rodeck)?

One possibility is for a relatively quick, V-shaped downturn and recovery such as occurred in the early 1990s (starting with a recession that lasted for 8 months, from July 1990 to March 1991, followed by a relatively speedy recovery).

It’s a rosy forecast that has been offered by such theoretical and politically different economists as Gregory Mankiw (putting on his optimist cap) and Dean Baker, as well as a couple of my friends (in private communications). The basic idea is that the crisis was caused not by capitalism’s “inner workings” (such as the bursting of a speculative bubble or a decline in the profit rate), but by the pandemic and the government-mandated shutdown of businesses. So, the logic goes, as soon as the shutdowns are lifted, businesses will reopen, workers who were furloughed or laid off will head back to their employers, and spending (both consumption and investment) will rebound.

In other words, capitalists will be able to bury the bodies (both literally and figuratively) and get back to business as usual—although it’s quite possible, even then, that U.S. capitalism itself will look quite different (with increased concentration, especially in the retail sector, and even more inequality).

A second, less-optimistic picture is a U-shaped cycle, with a prolonged downturn and extended trough, and thus a delayed recovery—something like the United States experienced during the Second Great Depression (the so-called Great Recession itself lasted 18 months from peak to trough). Here, we’re talking about a much longer decline in economic growth (comprising 5 quarters of negative real GDP growth, from early 2008 to mid-2009) with soaring unemployment (reaching a peak of 10 percent), and, of course, an almost complete meltdown of the financial sector.

We don’t yet know how severe economic growth is or will be (although the authors of a recent National Bureau of Economic Research working paper forecast a year-on-year contraction in U.S. real GDP of nearly 11 percent as of the fourth quarter of 2020, while the 90-percent confidence interval extends to a nearly 20-percent contraction) but unemployment is already at an alarming level (18 percent, by my estimate) and will no doubt increase in the coming months.** Moreover, it’s quite possible that many of the workers who have been furloughed or laid off will not soon be reintegrated into their previous jobs or find, at least in the medium term, new jobs. That’s because many businesses will not reopen or will be acquired, as happens during every capitalist crisis, and the remaining businesses will resume with smaller workforces (e.g., because of automation and speed-ups). And, of course, certain sectors (such as transportation and any activity that involves large gatherings, such as professional and collegiate sports) will likely reopen very slowly.

In addition, a recent study suggests that forecasters (both researchers and government agencies) tend to be too optimistic about when recession recoveries will begin, which means the return to a normal economy could be slower and bumpier than many economists are currently predicting.

Finally, we still don’t know the likely trajectory of the pandemic, both within and across countries. Especially as tentative steps are being taken to reopen the U.S. economy, it’s quite possible, without widespread testing and an effective vaccine, that we’ll see a second or third wave of COVID-19, which will require new shutdowns.***

That leaves us, then, with a third possibility: a W-shaped recession and recovery, such as took place in the early 1980s, with an initial downturn (from January to July 1980) followed in short order by a second, more severe one (from July 1981 to November 1982).

Such a double-dip recession, with a short recovery inbetween, might occur if the economy is reopened and pent-up demand (for everything, from cars to the commodities in brick-and-mortar stores and restaurants) leads to a surge in consumption, but the initial recovery is disrupted by households attempting to rebalance their finances (e.g., to pay for healthcare and to make up for foregone paychecks) and businesses that, after selling off their inventories, curtail both new purchases and longer-term investment projects in the face of considerable uncertainty. That would mean a new round of furloughs and layoffs, even without new waves of the pandemic.

Of course, if the novel coronavirus does get out of control again (e.g., as recently happened in Singapore), either because of its spread from one region to another the United States or because of outbreaks abroad (which in coming months may be experiencing only the initial stages of the pandemic), then the likelihood of a W-shaped cycle would increase.

As I wrote at the top, I don’t make predictions, and I have no idea which of these three possibilities is most likely. What I do know is that the existing way of organizing economic and social life in the United States, which was already inflicting its pains and punishments on most of the American people while favoring a tiny group at the top, has proven to be even more poorly equipped to handle a pandemic. The public healthcare system, notwithstanding the heroic work of its workers, has clearly come up short. And the way the system has stranded workers and the owners of small businesses, who have barely benefited from the bailouts that have mostly favored large banks and corporations, has made a terrible situation even worse.

Regardless of the depth of the recession and the speed of the recovery, the real debate in the months ahead will center on one question: what fundamental changes need to be made so that, in moving forward, the grotesquely unequal imposition and shifting of burdens favored by American economic and political elites can finally be eliminated?

*The designation of a recession is the province of a committee at the National Bureau of Economic Research. Contrary to popular belief, which equates a recession with two consecutive quarters of negative GDP growth, an NBER recession is a monthly concept that takes into account a number of monthly indicators—such as employment, personal income, and industrial production—as well as quarterly GDP growth. And just to be clear, the NBER does not have or utilize a separate category or metric for capitalism’s depressions.

**According to a newly released poll from the Pew Research Center, 43 percent of American adults say their households have suffered a job loss or a cut in pay since the start of the coronavirus crisis, marking a 10-point increase from a month ago. Among lower-income adults (with annual incomes less than roughly $37,500), an even higher share (52 percent) say they or someone in their household has experienced this type of job upheaval.

***The CDC is now warning that a second wave of the novel coronavirus later this year may be far more dire because it is likely to coincide with the start of flu season.

[…] existing alphabet soup of possible recoveries—V, U, W, and so on (which I discussed back in April)—is clearly inadequate to describe what has been taking place in the United States […]

[…] existing alphabet soup of possible recoveries—V, U, W, and so on (which I discussed back in April)—is clearly inadequate to describe what has been taking place in the United States […]

[…] existing alphabet soup of possible recoveries—V, U, W, and so on (which I discussed back in April)—is clearly inadequate to describe what has been taking place in the United States […]