Special mention

Posts Tagged ‘Georgia’

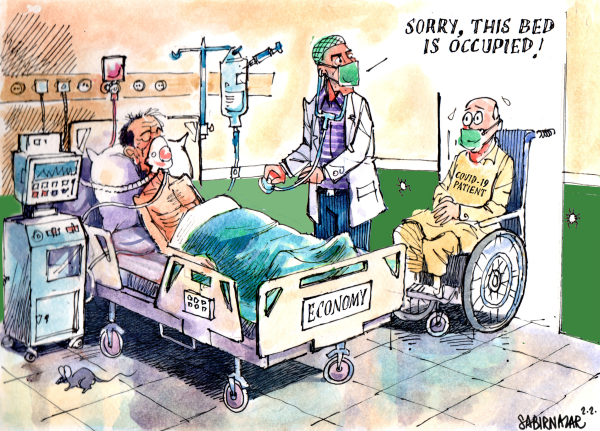

Cartoon of the day

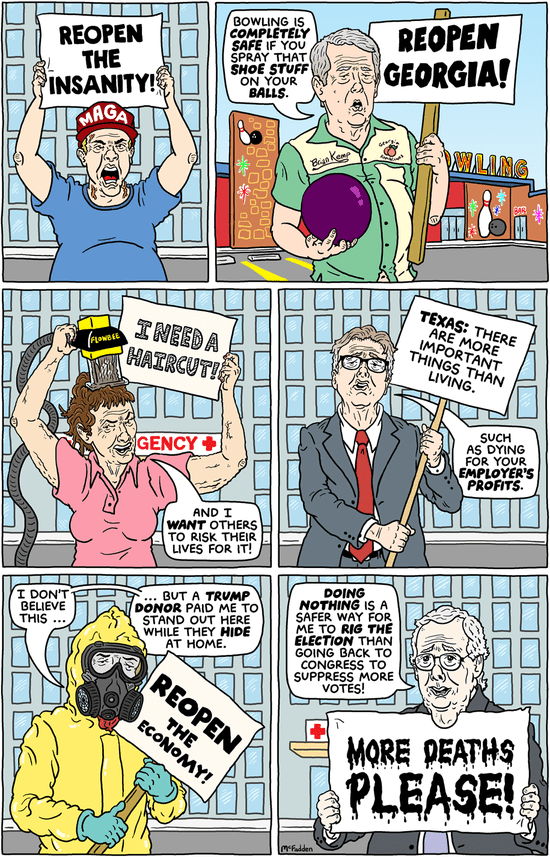

Posted: 28 April 2020 in UncategorizedTags: cartoon, coronavirus, corporations, economy, election, Georgia, MAGA, Mitch McConnell, pandemic, profits, Texas, Trump

0

Unemployment claims—pandemic edition

Posted: 23 April 2020 in UncategorizedTags: capitalism, chart, coronavirus, Georgia, insurance, pandemic, slavery, unemployment, workers

What the hell is Georgia Governor Brian Kemp doing, deciding to reopen the state’s economy?

Georgia was one of the last states to close, and has now adopted the most aggressive plan to reopen. But the mayors of the state’s major cities—such as Atlanta, Athens, and Savannah—are certainly opposed to the idea. As is Dr. Anthony S. Fauci, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Even “raring to go by Easter” Donald Trump thinks (or at least said, at the urging of Dr. Deborah Birx) Kemp’s decision was too hasty!

As of yesterday afternoon, Georgia (according to the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center) had tested only 88, 425 of its 10.74 million residents, with 20,740 confirmed cases of COVID-19 and 798 deaths. Moreover, expected coronavirus peaks—of hospital use (1 May) and deaths (3 May)—are still are still more than a week away.

So, what the hell is going on?

Well, according to George Chidi, a Georgia journalist and former staff writer for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution (via American historian Heather Cox Richardson [ht: lw]), it’s pretty straightforward:

“It’s about making sure people can’t file unemployment,” he wrote.

The state’s unemployment fund has about $2.6 billion. The shutdown has made claims skyrocket—Chidi says the fund will empty in about 28 weeks. There is no easy way to replenish the account because Georgia has recently set a limit on income taxes that cannot be overridden without a constitutional amendment. It cannot borrow enough to cover the fund either, because by law Georgia can’t borrow more than 5% of its previous year’s revenue in any year, and any borrowing must be repaid in full before the state can borrow any more.

By ending the business closures, Kemp guarantees that workers can no longer claim they are involuntarily unemployed, and so cannot claim unemployment benefits. Chidi notes that the order did not include banks, software firms, factories, or schools. It covered businesses usually staffed by poorer people that Kemp wants to keep off the unemployment rolls.

That makes a lot of sense.

But to my mind it’s not just about state finances, since the federal government (according to the CARES Act) is picking up the extra amount ($600) for unemployment claims. It’s about disciplining and punishing low-income workers.

As it turns out, unemployment benefits are—by U.S. standards, which admittedly is a very low bar—pretty generous right now. At least until the end of July, when the additional payments expire.

Taking the national average unemployment insurance benefit of $377.97 as the baseline, the new amount of the average unemployment check should (until the act expires) be around $978 ($600 + $378). This amount is equal to the average weekly earnings in the private (nonfarm) sector in the United States, and exceeds the average weekly paycheck for at least some of the industries (such as retail and leisure and hospitality) hit the hardest by COVID-19, as seen in the table I compiled above.

Now, that’s not enough (as conservative critics have complained) for workers to find a way of getting fired from their jobs, in order to collect unemployment. They’d still have to worry about the loss of any benefits (such as health insurance) from their employers, and they’d eventually have to begin the search for a new job. But it certainly does create a floor under their pay and allow them some space to do the only sane thing workers should be doing right now: staying home.

Kemp’s decision, to make “sure people can’t file unemployment,” follows a very different logic. It makes Georgian workers desperate, which forces them to have the freedom to sell their ability to work to employers, regardless of the consequences.

That, alas, is the way the modern equivalent of slavery works—in Georgia and across the United States. It’s not whips and chains; it’s the need to work for someone else, to get a wage to purchase the commodities necessary for survival.

Right now, workers who are being forced to have the freedom to go to work also means spreading the contagion, thereby endangering themselves and the communities in which they live.

And perhaps die.

Protest of the day

Posted: 28 May 2012 in UncategorizedTags: Appalachia, California, coal, Georgia, Ohio, prisoners, protests, race, Virginia

On May 22, prisoners at Virginia’s Red Onion State Prison [ht: db] began a hunger strike.

The series started Dec. 9, 2010, with a sit-down strike by thousands of prisoners in Georgia, tired of being forced to work for free like slaves, followed by Lucasville prisoners’ hunger strike at Ohio State Penitentiary in January 2011 and the mass hunger strikes in California beginning July 1, 2011, that involved 12,000 prisoners in 13 prisons simultaneously refusing food at their peak. Hunger strikes worldwide, from Palestine, where prisoners acknowledged being inspired by their peers in California, to Kyrgysztan, where prisoners literally sewed their mouths shut, have followed.

Red Onion State Prison in rural Virginia sits in the barren crater of a formerly lush green mountain whose top was blown off to remove the coal that used to be mined the old-fashioned way. Built in 1998, it’s the new economic development model for Appalachia: mountaintop removal covered by prisons and Wal-Marts, now the only job options for out-of-work miners and their families, according to JJ Heyward, a veteran activist who volunteered at the Bay View before moving to the East Coast.

Now the miners who used to mine “black gold” – coal – mind Black prisoners. Heyward says that Washington, D.C., has no prisons, so anyone sentenced to five years or more is shipped out of state, often to Red Onion, culturally a world away.