The paradox of the 2016 presidential race is that both major party candidates claim (or at least are identified by those in the media with) support of portions of the U.S. working-class and yet neither campaign offers anything in the way of concrete policies or strategies that actually respond to the real issues and problems faced by the members of the working-class.

Donald Trump’s supporters, for example, are more likely to be white workers in blue-collar fields who have less education—and yet the candidate himself, even though he criticizes the loss of manufacturing jobs and the anti-labor bias of free-trade agreements, has argued that American workers’ wages are too high and economic policy should focus on lowering tax rates for corporations and wealthy individuals. Meanwhile, the Podesta emails show that Hillary Clinton has no plans to reward the labor movement’s unwavering loyalty or record contributions to her campaign, especially those organizing hourly workers at Walmart and fast-food chains.

So, regardless of who wins the election on 8 November, the condition of the working-class in the United States will likely be ignored.

The biggest obstacle to considering the actual situation the American working-class finds itself in is the presumption that the working-class is white and everyone else is an “identity” group, as if most members of other ethnic and racial groups—especially Blacks and Hispanics—aren’t themselves members of the working-class. The fact is, most Americans are forced to have the freedom to sell their ability to work to someone else and, while there are differences in both position and ideas (as there always are within a group as large as the working-class), they constitute the majority who as they work produce a surplus that is appropriated by a small group of employers (some of which, in turn, is distributed to a somewhat larger group of executives and supervisors).

In terms of numbers I’ve illustrated before, we’re talking grosso modo about the top 1 percent and the rest of the top 10 percent versus the bottom 90 percent—whose shares of national income have been moving in opposite directions for the better part of the past three and a half decades.

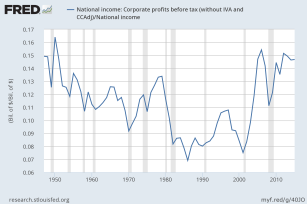

And the key reason the shares of national income going to the top 1 percent and the rest of the top 10 percent have been growing and the share going to the bottom 90 percent has been falling is the fact that, as I’ve shown before, the profit and wage shares have also been moving in opposing directions in recent decades.

Not surprisingly, as depicted in the chart above, the ownership of wealth is even more unevenly distributed between the working-class and those at the top. (The only major difference between changes in the distribution of income and wealth since 1979 is the fact that the share of wealth owned by the members of the top 10 percent exclusive of the top 1 percent has actually declined, from 43.1 percent to 35.4 percent.)

But, of course, the deteriorating condition of the U.S. working-class goes beyond the obscene (and still-growing) inequalities in the distribution of income and wealth. As both a condition and consequence of those inequalities, working-class Americans have suffered from mass unemployment (reaching 1 in 10 workers, according to the official rate, in October 2009, and much higher if we include discouraged workers and those who have underemployed), real wages that have been flat or falling for decades (now below what they were in the mid-1970s) along with declining benefits, a precipitous decline in unions (from one quarter in the 1970s to about ten percent today), an increase in the number of hours worked (both the length of the workweek and the average number of weeks worked per year), a significant rise in the incidence of “alternative work arrangements” (such as temporary help agency workers, on-call workers, contract workers, and independent contractors or freelancers), and most people think good jobs are difficult to find where they live (by a factor of 2 to 1)—not to mention increasing mortality (for the first time since the 1950s), an increase in differences in life expectancy between those at the top and everyone else, high levels of infant mortality, a spectacular growth in the rate of incarceration, and increasing indebtedness (especially for student and auto loans).

Overall, the working-class in the United States has not shared in the increased prosperity of the nation in recent decades, and has carried more than its share of the costs of the Great Recession in recent years. American workers have been producing a larger and larger surplus. But it’s not going to them. It is appropriated by their employers, who keep some within their enterprises (for investment and, increasingly, for other purposes, such as mergers and acquisitions) and distribute the rest to those who manage the operations of those enterprises (who, in turn, engage in conspicuous consumption and purchase financial assets). That’s why there’s a growing gap—by every conceivable measure—between those at the top and the U.S. working-class.

It’s no wonder, then, that over the course of the past year and a half American workers have rejected establishment politics—as offered by both Democrats and Republicans—and voted in large numbers for Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump. They’re simply fed up with an economic system that has been rigged to benefit only a small group at the top and frustrated by a set of political candidates (not to mention economists and economic pundits) who pronounce fundamental change to be undesirable and unrealistic. Better to stay the course, so the elites preach, and eventually trickledown economics will work.

But, as George Packer explains,

the élites on each side of the partisan divide have more in common with one another than they do with voters down below. A network-systems administrator, an oil-and-gas-company vice-president, a journalist, and a dermatologist hire nannies from the same countries, dine at the same Thai restaurants, travel abroad on the same frequent-flier miles, and invest in the same emerging-markets index funds. They might have different political views, but they share a common interest in the existing global order. . .

Democrats can no longer really claim to be the party of working people—not white ones, anyway. Those voters, especially men, have become the Republican base, and the Republican Party has experienced the 2016 election as an agonizing schism, a hostile takeover by its own rank and file. Conservative leaders had taken the base for granted for so long that, when Trump burst into the race, in the summer of 2015, they were confounded. Some scoffed at him, others patronized him, but for months they didn’t take him seriously. He didn’t sound like a conservative at all. . .

The great truth was that large numbers of Republican voters, especially less educated ones, weren’t constitutional originalists, libertarian free traders, members of the Federalist Society, or devout readers of the Wall Street Journal editorial page. They actually wanted government to do more things that benefitted them (as opposed to benefitting people they saw as undeserving).

Right now, the working-class finds itself divided—without a party of its own and forced to choose between two presidential candidates with the highest unfavorable ratings in modern history. In recent elections, the Democratic candidate has lost among one portion—whites, without a college degree—of the working-class.* But Democrats have gained among other portions—Hispanics, Blacks, young people, and those with a college degree—and, in 2016, they’re counting on that same coalition.

The actual result is going to depend on turnout among different parts of the working-class. Clinton, who is clinging to a deteriorating lead over Trump, is faced with a slump in early Black voter turnout.** Trump, for his part, would need a turnout among non-college-educated white voters that equals that of college-educated whites in order to win.

The problem, of course, is neither major-party candidate offers a convincing response to the real issues faced by the U.S. working-class—as a whole much less to its diverse resentments and desires, its multiple identities and aspirations.

And what happens to the working-class once the election is over? My suspicion is, if Clinton manages to hang on to her lead, the injuries and insults visited upon the working-class in recent years and decades will quickly be forgotten. Ironically, only if Trump finds a way to win will the working-class be afforded any ongoing attention—but then only one portion and only in terms of their decision to vote based on “fear and resentment occasioned by a loss of identity and standing.”

But, in either case, the condition of the working-class in the United States will continue to deteriorate and to be ignored by those at the top.

*As Ruy Teixeira and John Halpin explain, “the worst performance came in 2012 when Obama lost this group—once the bulwark of the Democratic coalition—by a staggering 26 points (62-36).”

**But, according to the New York Times, “Working in Mrs. Clinton’s favor even if her share of the black vote declines is the fact that she has built a political coalition different from Mr. Obama’s. She is counting on an electorate that is more Hispanic and includes more white voters — especially college-educated women — who would have considered voting Republican but are repelled by Mr. Trump.”

[…] Condition of the working-class in the United States | occasional links & commentary on What about the white working-class? […]

[…] the course of this past year, I warned on numerous occasions (e.g., here, here, and here) we needed to pay more attention to the ways class politics were playing out in the 2016 […]

[…] understand they’re not the sole or even main cause for the deteriorating condition the U.S. working-class has found itself in recent years and decades. Neoliberalism is not just globalization, as it […]

[…] understand they’re not the sole or even main cause for the deteriorating condition the U.S. working-class has found itself in recent years and decades. Neoliberalism is not just globalization, as it […]

[…] understand they’re not the sole or even main cause for the deteriorating condition the U.S. working-class has found itself in recent years and decades. Neoliberalism is not just globalization, as it […]

[…] Why Mainstream Economists Are Responsible for Electing Donald Trump – Evonomics on Condition of the working-class in the United States […]

[…] November—Condition of the working-class in the United States […]

[…] focus on that last claim. As regular readers of this blog know, income inequality—whether measured in terms of fractiles (e.g., the 1 percent versus everyone else) or classes […]

[…] focus on that last claim. As regular readers of this blog know, income inequality—whether measured in terms of fractiles (e.g., the 1 percent versus everyone else) or classes […]

[…] it is also the case that overall, as I argued last November, the deteriorating condition of the U.S. working-class includes but goes beyond the […]

[…] fall, just before the presidential election, I posted a report on the perilous condition of the American […]

[…] fall, just before the presidential election, I posted a report on the perilous condition of the American […]

[…] already knew a great deal about the perilous condition of the American working-class and the terrible condition of the American workplace. Now we know that American workers are facing […]

[…] mainstream intellectuals within American democracy first created and then failed to respond to. As I explained last […]

[…] mainstream intellectuals within American democracy first created and then failed to respond to. As I explained last […]

[…] mainstream intellectuals within American democracy first created and then failed to respond to. As I explained last […]