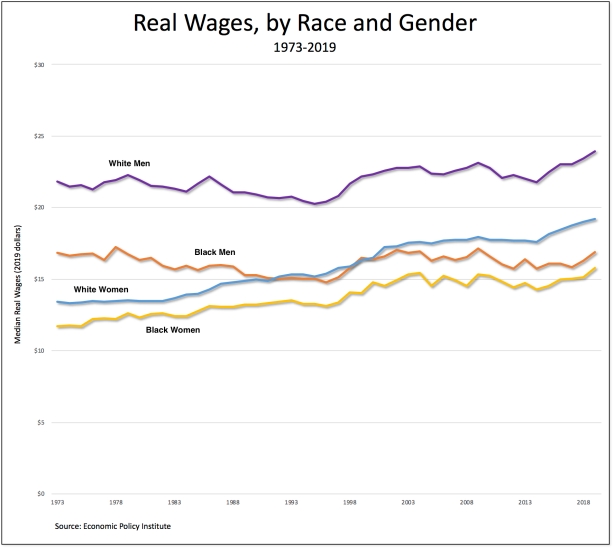

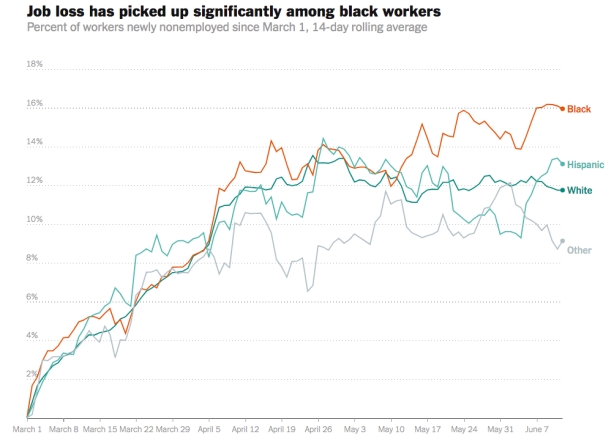

It’s clear, at least to many of us, that if the United States had a larger, stronger union movement things would be much better right now. There would be fewer cases and deaths from the novel coronavirus pandemic, since workers would be better paid and have more workplace protections. There would be fewer layoffs, since workers would have been able to bargain for a different way of handling the commercial shutdown. And there would be more equality between black and white workers, especially at the lower end of the wage scale.

But, in fact, the American union movement has been declining for decades now, especially in the private sector. Just since 1983, the overall unionization rate has fallen by almost half, from 20.1 percent to 10.3 percent. That’s mostly because the percentage of private-sector workers in unions has decreased dramatically, from 16.8 percent to 6.2 percent. And even public-sector unions have been weakened, declining from a high of 38.7 percent in 1994 to 33.6 percent last year.

The situation is so dire that even Harvard economist Larry Summers (along with his coauthor Anna Stansbury) has had to recognize that the “broad-based decline in worker power” is primarily responsible for “inequality, low pay and poor work conditions” in the United States.*

Summers is, of course, the extreme mainstream economist who has ignited controversy on many occasions over the years. The latest is when he was identified as one as one of Joe Biden’s economic advisers back in April. Is this an example, then, of a shift in the economic common sense I suggested might be occurring in the midst of the pandemic? Or is it just a case of belatedly identifying the positive role played by labor unions now that they’re weak and ineffective and it’s safe for to do so?

I’m not in a position to answer those questions. What I do know is that the theoretical framework that informs Summers’s work has mostly prevented him and the vast majority of other mainstream economists from seeing and analyzing issues of power, struggle, and class exploitation that haunt like dangerous specters this particular piece of research.

Let’s start with the story told by Summers and Stansbury. Their basic argument is that a “broad-based decline in worker power”—and not globalization, technological change, or rising monopoly power—is the best explanation for the increase in corporate profitability and the decline in the labor share of national income over the past forty years.

Worker power—arising from unionization or the threat of union organizing, firms being run partly in the interests of workers as stakeholders, and/or from efficiency wage effects—enables workers to increase their pay above the level that would prevail in the absence of such bargaining power.

So far, so good. American workers and labor unions have been under assault for decades now, and their ability to bargain over wages and working conditions has in fact been eroded. The result has been a dramatic redistribution of income from labor to capital.

Clearly, as readers can see in the chart above, using official statistics, the labor share of national income fell precipitously, by almost 10 percent, from 1983 to 2020.**

Not surprisingly, again using official statistics, the profit rate has risen over time. The trendline (the black line in the chart above), across the ups and downs of business cycles, has a clear upward trajectory.***

Over the course of the last four decades is that, as workers and labor unions have been decimated, corporations have been able to pump out more surplus from their workers, thereby lowering the wage share and increasing the profit rate.

But that’s not how things look in the Summers-Stansbury world. In their view, worker power only gives workers an ability to receive a share of the rents generated by companies operating in imperfectly competitive product markets. So, theirs is still a story that relies on exceptions to perfect competition, the baseline model in the world of mainstream economic theory.

And that’s why, while their analysis seems at first glance to be pro-worker and pro-union, and therefore amenable to the concerns of dogmatic centrists, Summers and Stansbury hedge their bets by references to “countervailing power,” the risk of increasing unemployment, and “interferences with pure markets” that “may not enhance efficiency” if measures are taken to enhance worker power.

Still, within the severe constraints imposed by mainstream economic theory, moments of insight do in fact emerge. Summers and Stansbury do admit that the wage-profit conflict that is at the center of their story does explain the grotesque levels of inequality that have come to characterize U.S. capitalism in recent decades—since “some of the lost labor rents for the majority of workers may have been redistributed to high-earning executives (as well as capital owners).” Therefore, in their view, “the decline in labor rents could account for a large fraction of the increase in the income share of the top 1% over recent decades.”

The real test of their approach would be what happens to workers’ wages and capitalists’ profits in the absence of imperfect competition. According to Summers and Stansbury, workers would receive the full value of their marginal productivity, and there would be no need for labor unions. In other words, no power, no struggle, and no class exploitation.

That’s certainly not what the world of capitalism looks like outside the confines of mainstream economic extremism. It’s always been an economic and social landscape of unequal power, intense struggle, and ongoing class exploitation.

The only difference in recent decades is that capital has become much stronger and labor weaker, at least in part because of the theories and policies produced and disseminated by mainstream economists like Summers and Stansbury. Now, as they stand at the gates of hell, it may just be too late for their extreme views and the economic and social system they have so long celebrated.

*The link in the text is to the column by Summers and Stansbury published in the Washington Post. That essay is based on their research paper, published in May by the National Bureau of Economic Research.

**We need to remember that the labor share as calculated by the Bureau of Labor Statistics includes incomes (such as the salaries of corporate executives) that should be excluded, since they represent distributions of corporate profits.

***I’ve calculated the profit as the sum of the net operating surpluses of the nonfinancial and domestic financial sectors divided by the net value added of the nonfinancial sector. The idea is that the profits of both sectors originate in the nonfinancial sector, a portion of which is distributed to and realized by financial enterprises. The trendline is a second-degree polynomial.