Before he was killed, George Floyd worked as a truck, a bouncer, and a security guard. Ahmaud Arbery worked at his father’s car wash and landscaping business, and previously held a job at McDonald’s. Breonna Taylor was a certified Emergency Medical Technician who had two jobs at hospitals in Louisville, Kentucky. Eric Garner worked as a mechanic and then in New York City’s horticulture department for several years before health problems, including asthma, sleep apnea, and complications from diabetes, forced him to quit. Trayvon Martin was the son of a program coordinator for the Miami Dade Housing Authority and a truck driver; he washed cars, babysat, and cut grass to earn his own money.

All of them, and most of the other African Americans who have been killed in recent years (by the police or other Americans), were members of the black working-class in the United States.

The history of the black working-class begins, of course, with slavery and then continues—with almost-incessant violence, from slave patrols through lynchings to beatings and deaths at the hands of law enforcement and incarceration by the criminal justice system— through southern sharecropping, the Great Migration out of the rural South to the urban factories of the Northeast, Midwest, and West, and the panoply of jobs that currently exist in the public and private sectors of the United States.

For the purposes of this post, I want to focus on the most recent period—thus, from the end of the Great Migration, which roughly coincided with the assassinations of the two great Civil Rights leaders of the period, Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, Jr.

Even at the end of the Great Migration, more than half of the black working-class population remained in the South. But the region itself was changing, in large part because of the infrastructure associated with the spread of military bases and the subsequent industrialization of cities and towns in the non-cotton south—without however eliminating the anti-union, low-wage legacy of southern economies.

Meanwhile, in the North (both the Northeast and the Midwest), a large portion of black migrants managed to secure factory jobs. But the same migration channeled other black workers into the high-unemployment ghettos of northern cities, which if anything were worsening with the passage of time.

While in the first half of the twentieth century, labor unions had been anything but a positive force for black workers, by 1973 unionization rates among black men were over 40 percent, while rates among white men were between 30 and 40 percent.* And by the late 1970s, almost one quarter of black women—nearly double the share of white women—belonged to a union.

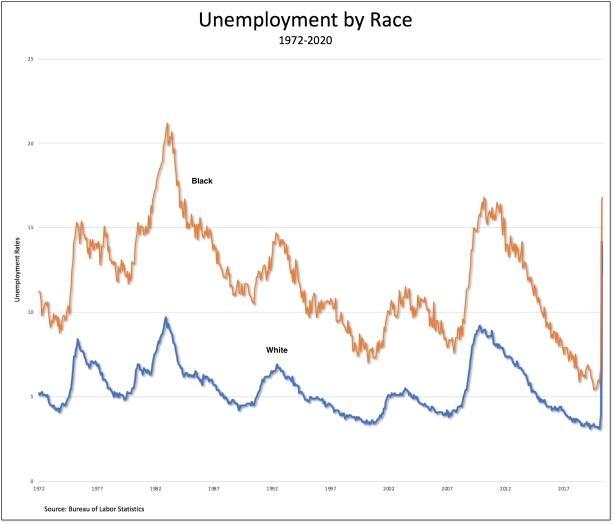

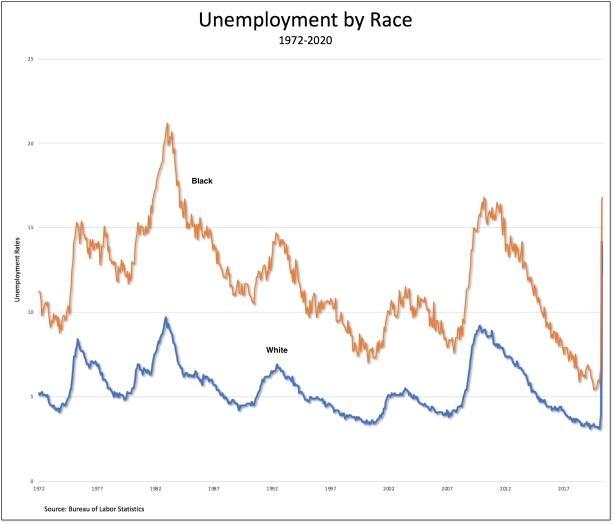

But, in 1972 (the first year for which data are available), the black unemployment rate was more than twice (2.15 times) that of white workers—which has persisted as an average, through the ups and downs of both unemployment rates, for the entire period down to the present.

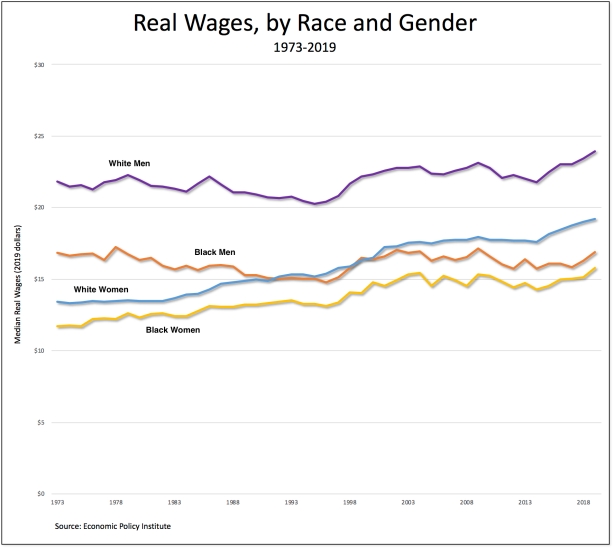

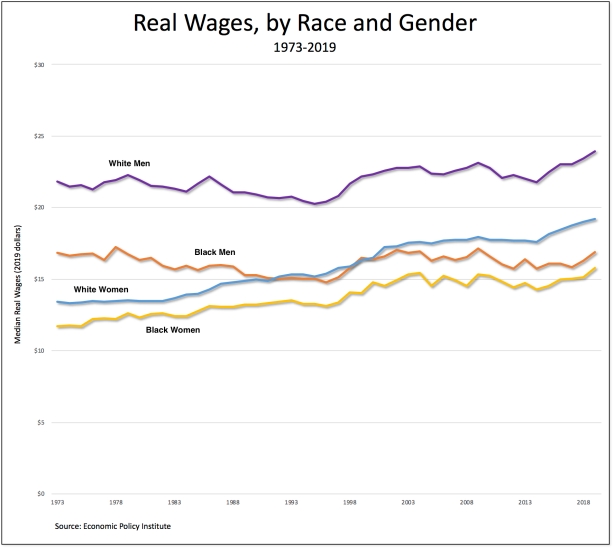

What about workers’ wages? In 1973, average (median) real wages of black workers were only 78 percent of white wages—and, while the percentage has varied over the decades (reaching a high of 84 percent in 1979, no doubt due to the influence of labor unions), by 2019 the percentage had fallen even lower, to 76 percent.

The wages of the black working-class (just like those of the white working-class) exhibited a clear hierarchy based on gender in the early 1970s. Black women earned on average 69 percent of what black men did (while white women’s wages were even less, about 62 percent of their male counterparts). But then some of the gaps began to decrease: between black women and men (as well as between white women and men). In fact, by 2019, black working-class women’s wages were 94 percent of those of black men (although, by then, white women’s wages were higher than both black men and women). But the wage gap between black and white men had actually grown—from 24.5 percent (in 1973) to 31.7 percent (in 2019).

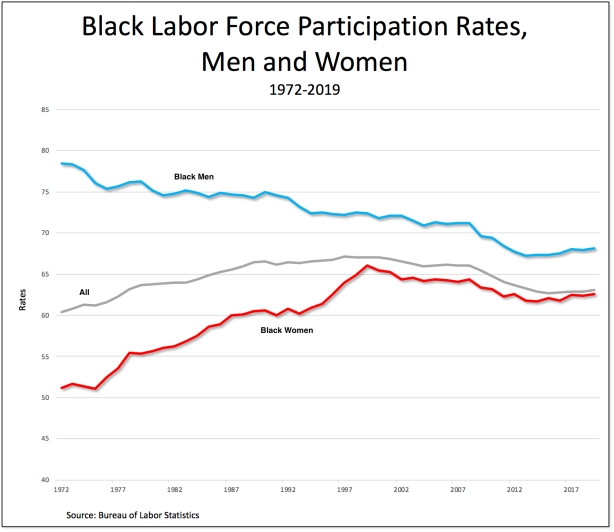

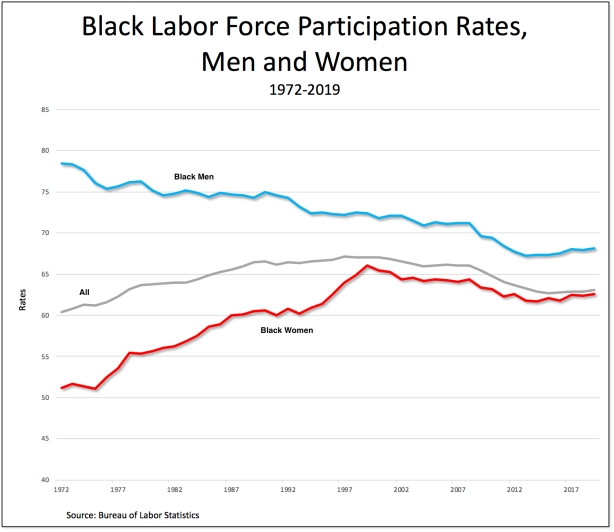

The gender composition of the black working-class both reflected and contributed to the changes in wage gaps over the past five decades. In 1972, the labor force participation rate of black men was much higher than that of black women: 78.5 percent compared to 51.1 percent. But the gap between the two rates has declined dramatically over time, both because the rate for men has fallen (largely due to the increased incarceration rate of black men) and the increase in the rate for women (as they became increasingly engaged in employment outside the household). So, even though both rates have fallen in recent decades (mirroring the nationwide decline in the labor force participation rate, the gray line in the chart), the changes between 1972 and 2019 for both groups are striking: the rate for black men had declined to 68.1 percent while that of black women had increased to 62.5 percent.

The result is that black women, who in 1972 made up 44.9 percent of the black civilian labor force, now comprise 52.5 percent. The share of black men has thus declined—from 55.12 percent to 47.5 percent.

While the victories of the Civil Rights Movement in dismantling Jim (and Jane) Crow laws were appropriately celebrated, the movement never succeeded in eliminating systemic or structural racism—from employment and housing discrimination through health disparities to the racial biases of the prison-industrial complex. Moreover, the initial progress in narrowing the wage gaps within the working-class coincided with a new assault on American workers and the dramatic growth in inequality in the U.S. economy as a whole. Racial capitalism in the United States therefore changed beginning in the late-1970s, leaving the American working-class—and, even more so, black (and Hispanic) workers—further and further behind the tiny group at the top.

By 2020, the increasing precarity of the black working-class made its members more exposed to physical attacks and police murders, the ravages of the novel coronavirus pandemic, and the negative effects of the economic crisis.

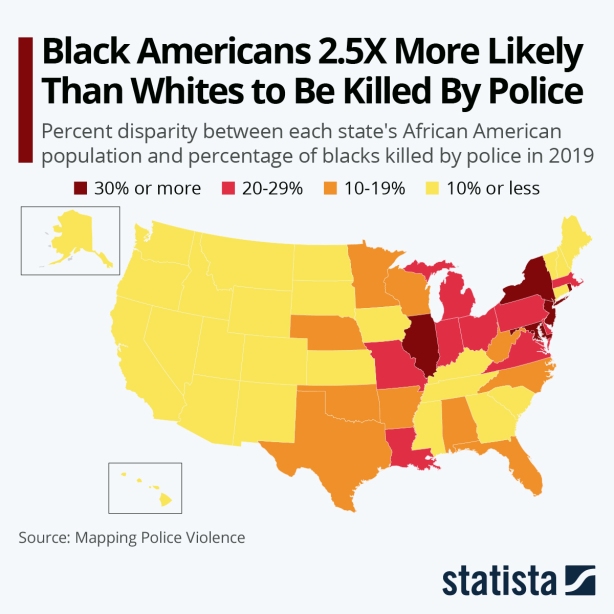

source

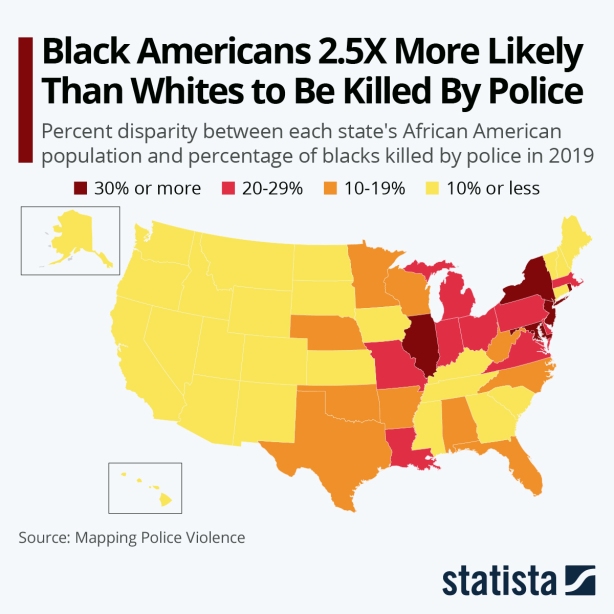

Last year, 24 percent of all police killings were of black Americans when just 13 percent of the U.S. population is black—an 11-point discrepancy. Mapping Police Violence also showed that 99 percent of all officers involved in all police killings were never charged.

The latest overall COVID-19 mortality rate for black Americans (compiled by the the APM Research Lab) is 2.3 times as high as the rate for whites, and they’re dying above their population share in 30 states and, most dramatically, in Washington, D.C.

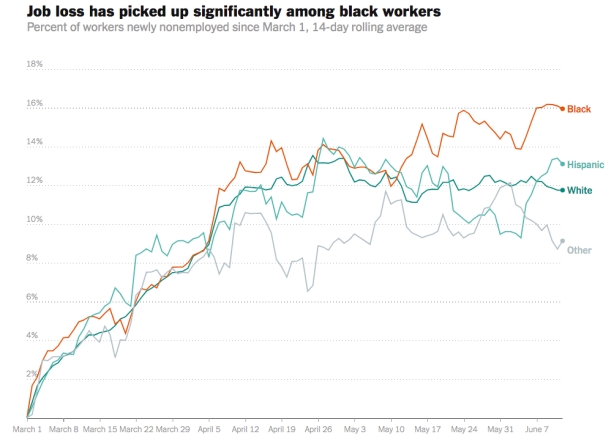

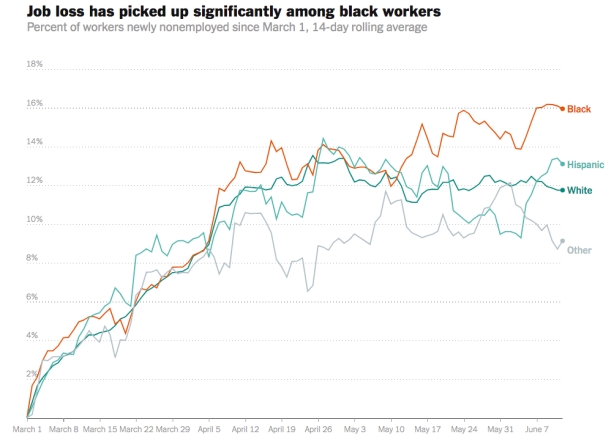

Even as the rate of layoffs has largely slowed over the past two months, black job losses rose in May and June relative to those of white workers. In fact, according to the New York Times,

For long stretches of the pandemic, black and white employment losses largely mirrored each other. But in the last month, layoffs among African-Americans have grown while white employment has risen slightly. Now, among all the black workers who were employed before the pandemic, one in six are no longer working.

And all indications are that the economic recovery, if and when there is one, will be both long and painful, especially for the African American working-class.

It has become increasingly clear, especially in recent weeks as a national uprising has responded to the deaths of Floyd and many other members of the black working-class at the hands of the police, that these incidents did not happen in isolation. It is therefore time for the American working-class—black, brown, and white—to overcome its divisions and confront the problem of racism head-on. That’s certainly how the Executive Board of the Communication Workers of America sees things:

The only pathway to a just society for all is deep, structural change. Justice for Black people is inextricably linked to justice for all working people – including White people. The bosses, the rich, and the corporate executives have known this fact and have used race as one of the most effective and destructive ways to divide workers. Unions have a duty to fight for power, dignity and the right to live for every working-class person in every place. Our fight and the issues we care about do not stop when workers punch out for the day and leave the garage, call center, office, or plant. . .

Thoughts and prayers aren’t enough. No amount of statements and press releases will bring back the lives lost and remedy the suffering our communities have to bear. We must move to action.

*According to Natalie Spievack,

In 1935, when the National Labor Relations Act gave workers the legal right to engage in collective bargaining, less than 1 percent of all union workers were black. Union formation excluded agricultural and domestic workers, occupations predominantly held by black workers, and largely left black workers unable to organize.

By the late 1960s and early 1970s, unions began to integrate. The manufacturing boom brought large numbers of black workers north to factories, the civil rights movement focused increasingly on economic issues, and the more liberal Congress of Industrial Organizations organized black workers.