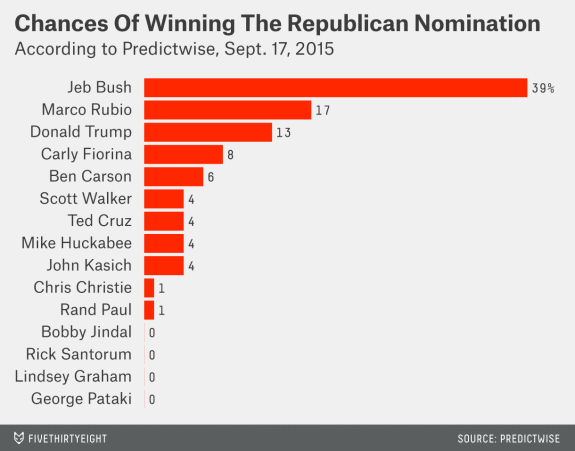

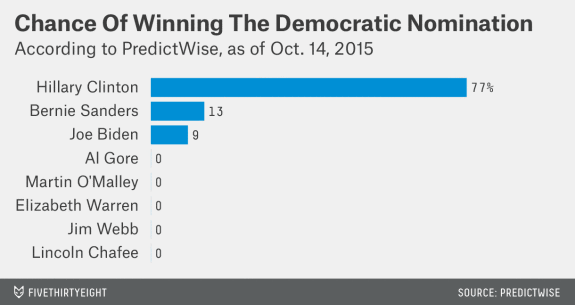

The argument I made 10 days ago about surprises—represented by Leicester City, Donald Trump, and Bernie Sanders—was meant as a reminder that the pundits are often wrong and unexpected events can, in fact, happen.*

But it is also the case that two of those examples are members of the oligocracy. Trump we all know about. Less known, as Toby Miller reminds us, is that the “Little Club That Could” is owned by King Power, whose boss is Thai oligarch Vichai Raksriaksorn.

King Power works with the controversial provincial strongman, machine politician, and fellow club owner Newin Chidchob, and thrives thanks to close ties to successive administrations and coup leaders. This is in keeping with Vichai’s status as someone who grew up with a cohort that gives and sustains favorable business conditions to those with the right political connections. It’s a well-established form of clientelism, and he plays it excellently.

Prior to winning the Premier League, Vichai’s singular sporting achievement was establishing the Thailand Polo Association. It connects him to global royalty, local military and police, and high society. The light of progressive glory and his relatives feature on the management committee, and have a British team linked to Leicester City.

In 2006, the body responsible for Thailand’s airports alleged that King Power had btained the retail concession and duty-free license for Suvarnabhumi Airport without an open bidding process. That governing board was soon replaced, and the scandal slipped into history, for all the world like Jamie Vardy’s anti-Asian casino rants or his red card against West Ham. King Power is widely believed to be selling goods from the world’s priciest luxury brands outside airport duty-free shops to rich men and their wives and girlfriends, undercutting the brands in Bangkok’s boutiques and creating considerable bad blood for the likes of Gucci and Louis Vuitton.

As the Bangkok Post wryly puts it, ‘King Power’s chief business acumen is in securing such monopolistic duty-free concessions in the first place and then to keep leveraging its myriad revenue streams. This is a murky area where business and politics intersect.’

No wonder the Financial Times says ‘Mr Vichai does not lack financial muscle and plays the same league as any football-club owning Russian oligarch or Gulf investment fund.’

So please, enough celebrating the happily lachrymose masculinity of the little club that could. Instead, let’s unleash some tears for those caught up in the exploitative nature of much Thai business life, or victims of the vicious “sport,” polo.

None of this diminishes the players’ achievement, the manager’s charm, or the fans’ pleasure. But the political-economic wonder that is the clue to the team’s popularity and romance should be investigated. The inequalities supped on by the likes of Leicester’s proprietors are no fairy tale come true, for all the winning of a Premiership.

I suppose that leaves the achievements of the Leicester players themselves and Bernie Sanders as the only real non-oligarchic surprises in the current season.

*And Nate Silver seems to agree: “it’s probably helpful to have a case like Trump in our collective memories. It’s a reminder that we live in an uncertain world and that both rigor and humility are needed when trying to make sense of it.” And, I would add, Leicester City and Bernie Sanders.