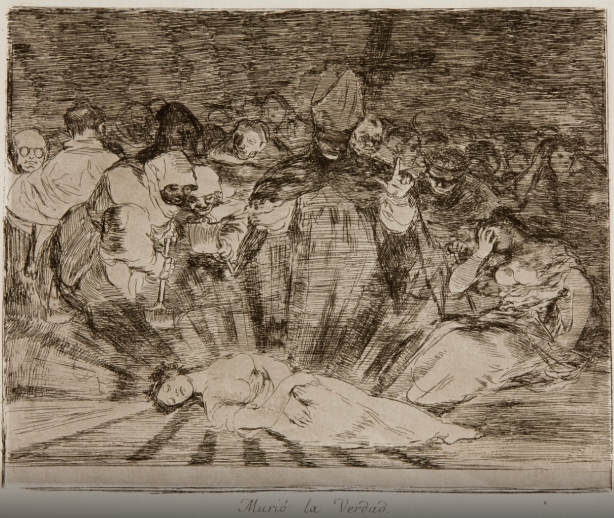

Francisco de Goya y Lucientes, “Murió la Verdad/Truth Has Died” (1814-15)

The liberal establishment continues to mourn the death of truth. Everyone else is moving on.

Every day, it seems, one or another liberal—pundit, columnist, or scholar—issues a warning that, in the age of Donald Trump, we now live in a post-truth world. In their view, we face a fundamental choice: either return to a singular, capital-t truth or suffer the consequences of multiple sets of beliefs, facts, and truths.

For example, just the other day, Keith Kahn-Harris [ht: ja] (in the Guardian) noted the “sheer profusion of voices, the plurality of opinions, the cacophony of the controversy,” which in his view “are enough to make anyone doubt what they should believe.” It’s what he calls “denialism”: the transformation of the “private sickness” of self-deception into the “public dogma” of seeing the world in a whole new way.

There are multiple kinds of denialists: from those who are sceptical of all established knowledge, to those who challenge one type of knowledge; from those who actively contribute to the creation of denialist scholarship, to those who quietly consume it; from those who burn with certainty, to those who are privately sceptical about their scepticism. What they all have in common, I would argue, is a particular type of desire. This desire – for something not to be true – is the driver of denialism.

Then, to ratchet up the morbid consequences of the death of truth, Kahn-Harris plays the ultimate trump card: contemporary denialism involves doubting the existence of the Holocaust, which in turn makes it possible “to publicly celebrate genocide once again, to revel in antisemitism’s finest hour.”

Olivia Paschal [ht: ja] (in the Atlantic) is concerned about a different facet of the world after truth: the role of repetition in creating beliefs that run counter to truth Thus, as she sees it, “even when people know a claim is false, just a few repetitions can make them more likely to think it’s true.” Such “illusory” truths serve to make false claims “familiar” and thus became ways of reframing the debate. Thus, according to Paschal, Fox News has been able to broadcast Trump’s claims (e.g., about the unfairness and inaccuracy of the Russia investigation), which “is also almost certainly contributing to their plausibility among the segments of the population that trust the network.”

As if in response, just yesterday, Margaret Sullivan (in the Washington Post) claimed that, among the consequences of the crisis in American newsrooms, is the decline of “common information—an agreed-upon set of facts to argue about.” So, she complains, in an already deeply divided nation, people turn to Facebook and cable news and thus “were deep in their own echo chambers and couldn’t seem to hear anything else.”

These are just three recent examples of a burgeoning series of complaints, and warnings about the dangers of a world in which a singular truth no longer holds and the need to restore such a truth (as if it once existed)—by challenging denialism, exposing illusory truths, and establishing a set of agree-upon facts.

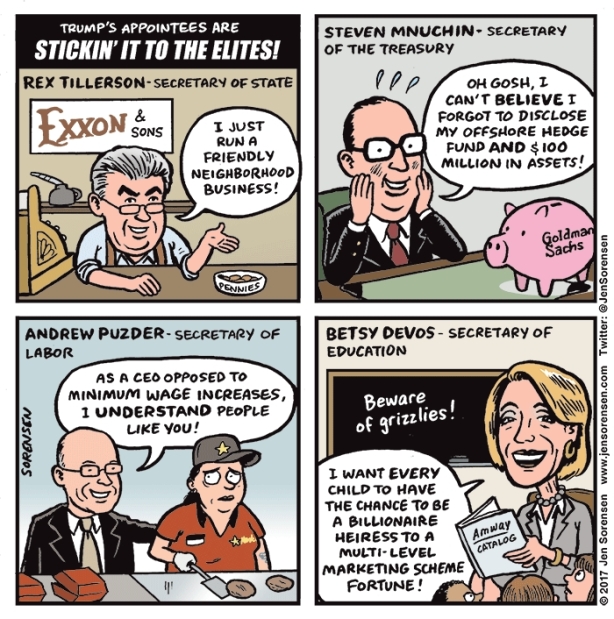

The “trauma” of Trump’s win just can’t make liberals stop writing this stuff. They keep trying their best to ask the nearly undisguised question: “are Trump supporters really human, like us?” This tells me that the members of the liberal establishment really thought they were never going to face another serious challenge to their ideological hegemony. And now that voters have had the temerity to defy the existing authority, liberals it seems can only dehumanize Trump supporters and, like the members of the Ancien Régime watching over the female cadaver of truth, hope their powers will eventually be restored.

Everyone else, however, is moving on—and a growing number of them are espousing socialist ideas or at least expressing support for them.

The turn to socialism stems in large part from the punishments meted out by the Second Great Depression and the lopsided nature of the recovery. It also represents a disenchantment with mainstream economists and their theories of capitalism, since they failed to consider even the possibility of a crisis in the years before 2007-08, and they didn’t haven’t anything useful to offer once the crash happened. Nor have mainstream economists (or pundits and politicians) been able to explain, much less suggest appropriate policies to undo, the obscene degree of inequality that has been steadily growing for decades now. And, of course, the rising cost of education, the unreliability of health insurance, and the growing precariousness of the workplace have left young people with gnawing material insecurity—and an interest in socialism.

Additional impetus has come from the spectacular—and largely unexpected—successes of Bernie Sanders’s campaign for the presidential nomination of the Democratic Party. And just this past June Americans witnessed the surprising electoral victory of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, a self-proclaimed democratic socialist, against ten-term House incumbent Joe Crowley in a New York congressional primary.*

At a pace that appears to match, if not surpass, all the liberal complaints about the death of truth, mainstream American media outlets now regularly publish discussions of (including, but certainly not limited to, attacks on) socialism. There’s socialism in the New York Times, the Washington Post, on CNN, Vox, and on and on.

But, of course, authors in other publications have been thinking about and developing different definitions and approaches to socialism for much longer. One of the best, especially for a younger generation, is Jacobin, which recently included a piece by Neal Meyer on what democratic socialism might mean:

Like many progressives, we want to build a world where everyone has a right to food, healthcare, a good home, an enriching education, and a union job that pays well. We think this kind of economic security is necessary for people to live rich and creative lives — and to be truly free.

We want to guarantee all of this while stopping climate change and building an economy that’s ecologically sustainable. We want to build a world without war, where people in other countries are free from the fear of US military intervention and economic exploitation. And we want to end mass incarceration and police brutality, gender violence, intolerance towards queer people, job and housing discrimination, deportations, and all other forms of oppression.

Unlike many progressives however, we’ve come to the conclusion that to build this better world it’s going to take a lot more work than winning an election and passing incremental reforms.

That’s pretty general but, at this early stage of the new, revitalized discussion of socialism in the United States, it’s a pretty good start.

It certainly moves us beyond the seemingly endless series of teeth-gnashing complaints about the perils of the post-truth world and charts a different path forward, which involves among other things a recognition of the real resentments and desires of working-class Americans, including those who voted for Trump.

Me, I’ll take socialism over truth any day.

*According to CNN, the excitement surrounding Ocasio-Cortez’s June stunner spurred another spike in dues-paying members of Democratic Socialists of America. The group now claims to have more than 45,000 members nationally.